The death of a child – in theatre – is tragedy. The decline of a parent, perplexity. Most western theatregoers don’t live in melodrama, but in the mess of every day, inching forward in anxiety. Theatre can offer the consolation of an underexplored situation being known: it’s something to be seen. Three times recently I’ve wandered out of the theatre almost in a daze, hollowed out by productions that staged the slope of ageing, and of caring. All three quietly excavate new theatrical territory, finding tender ways of playing, innovative ways of staging, this subject matter.

What is striking is that it is younger theatre makers who are exploring old age. Stoppard, Churchill and Frayn haven’t ventured there. Yet Florian Zeller was only 33 when The Father premiered in France in 2012. Barney Norris wrote Visitors for Up In Arms at 27; Selma Dimitrijevic, 40, writes and directs Gods Are Fallen and All Safety Gone for Greyscale. Old age, and what it means for families, for social and healthcare networks and of course for elderly individuals themselves, will demand attention as we live with an ageing population. These productions don’t present the bigger picture: all three twist around the vexed, intimate bond between parent and adult child. A relationship frayed by illness, tightened by concern, tripwired by obligation, love and grief.

Slow decline, an almost imperceptible shift into a new reality, could resist reflection in time-bounded performance. Visitors was the most familiar in form – inviting us into a home, its furniture worn by familiarity, eavesdropping on scenes set over several weeks as Edie, an elderly farmer’s wife, slowly declined. Norris’ generous naturalism absorbed us into the household dynamic, rippled by a young carer and maladroit son. I’ve always found it difficult to describe how Linda Bassett, an unsung marvel of British theatre, works. You can’t pinpoint physical or vocal tricks, displays of charisma or transformation. I only know that through barely apparent means she shows us into her characters’ souls. When those characters offer grey-toned states like apprehension, suspicion, care, she’s peerless. Here, in Alice Hamilton’s production, she let us sit alongside Edie’s warmth and confusion, with a poignancy that grasped your heart.

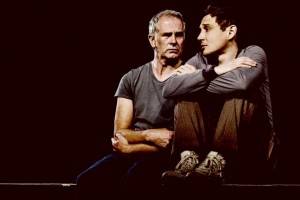

Kenneth Cranham’s performance in The Father is more obviously barnstorming, as befits André, an overbearing patriarch in denial of his illness. Zeller – in Christopher Hampson’s lucid version – gives us a sense of André’s reality through a painfully spry theatricality. André is beset by dementia, and it looks like theatre. Furniture vanishes between scenes from Miriam Buether’s scrupulous white box set. André doesn’t always recognise the person playing his daughter – and neither do we. He has no idea if a menacing, jocular man is really his daughter’s ex husband. Us either.

From the inside

One of the mysteries of dementia is what it must feel like from the inside. Scrabbling for a memory that doesn’t come. Unaware that memories have been lost, as if pages fall from the atlas. I try, but I can’t truly feel it. So Zeller’s act of theatrical imagining is immense, and in James Macdonald’s production, Cranham anchors it in intensely-realised distress. A favourite actor of Pinter, he has a bullish, gravelly authority, a squeezebox set of lungs, so his sense of powerlessness is destabilising. He’s beautifully counterposed by Claire Skinner – blanched, twisting thin-twig fingers, nerves down to the wire – playing his daughter (most of the time). Her reality is the burden of care, and you can almost hear her temples throbbing from the back of the stalls. The final image is Cranham’s great red face, tucked between white sheets and pillows, his glassy blue eyes blinking in distress, all consolation and security dropped away. It’s awful even typing the image back into my mind.

In Gods Are Fallen and All Safety Gone (a quote from Steinbeck’s East of Eden), Dimitrijevic shapes the awful sorrow of parental illness with quiet rigour. The stage is all but bare, with a small table at the side where two people attempt a jigsaw puzzle. On stage, two gentle blokes: one tall and silvered, the other shorter, hairier. One man playing the ma, the other her daughter.

There’s no furniture, but the relationship is as deeply grooved as the dint in the carpet beneath the family sofa. Four conversations are separated by extended silence. The first three each tread a similar path, though with factual variations (how is Auntie Marie? Is the daughter still with her boyfriend? Did she piss in the shower?). Meanwhile, the actors shuttle around each other on the small stage, swerving and looping and juddering to a halt as the relationship follows its timeworn grooves. Only in the third, when the daughter becomes confrontational, do we worry whether the mother is being everyday exasperating, or something more concerning. The fourth scene, seated, allows a belated sharing of truths.

Visitors and The Father must be exposing for their central performers, enacting a situation which may one day be their own. Greyscale’s Sean Campion and Scott Turnbull stand at one remove from their material but are beautifully tender with ti and each other: they sometimes hug a pause too long, as if leaving space for each character to puzzle out the other. Campion’s mother, baffled within her own patterns of behaviour. Turnbull’s daughter, smiling with frustration and affection.

The jigsaw puzzlers are a real mother and daughter – a different pair every night, their presence keeping the men on the right side of travesty. When I saw the show, the women kept their eyes down on the fiddly game, but the mother couldn’t help looking up, and soon both were fully absorbed by the play. Smiling with recognition, frowning in concentration. Noise from the street outside the Camden People’s Theatre continually intrudes, but inside is all silent attention.

Lessons in feeling

The playwright David Eldridge recent cited John Osborne’s notion that he wanted to give an audience ‘lessons in feeling.’ It isn’t necessarily a current notion, but its pertinent here – these three plays make you feel, for yourself, for others. It also says something about our unstable times, where austerity stretches out to the crack of doom, that younger artists are thinking about old age with such quiet dread. They should be writing fizzpop plays that thrust into a world they’re ready to inherit. Instead, they contemplate both their own ageing and, more pressingly, the likelihood of their own transformation into helicopter children, hovering anxiously over their parents while feeling unfit for the task. The gods are fallen, but we’re not ready to be gods in turn. Not yet. Not ever.

Photo (top): Kenneth Cranham in The Father. Photo: Simon Annand

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

[…] 2015-05-23 Ron Crotty, Bassist, 1929-2015 AJBlog: RiffTidesPublished 2015-05-22 The old story AJBlog: Performance MonkeyPublished 2015-05-22 Whether Villains or Martyrs They’re […]