The cruellest thing you can do to a performer is refuse to look at them. You might boo, heckle, catcall. Stamp your feet and throw a punch, Rite of Spring style. Raise an eyebrow and tut (aka the Surrey snub). Each of these may sting, but they at least engage. Crueller by far is to decline to step foot in the theatre. If a performance isn’t seen, does it exist?

Twenty years ago, a critic’s refusal to review a work paradoxically wrote it into history. In December 1994, Arlene Croce, then the doyenne of dance critics at the New Yorker, wrote an article in which she explained why she wouldn’t attend Still/Here, a multimedia dance piece by Bill T Jones at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Jones made Still/Here at the height of the moral panic over AIDS. He was himself HIV positive and his partner Arnie Zane had died in 1988. Jones, known for argumentative, eloquent dance works which took a provocative pop at American history and culture, thought of this as a work ‘that nobody would find controversial.’ He and his dancers interviewed people living with terminal illness, and some of these interviews appeared in footage by video artist Gretchen Bender.

Croce was having none of it. She predicted that the production would be ‘intolerably voyeuristic’ – ‘a kind of messianic travelling medical show’. In particular, she objected to the inclusion of words and images of the terminally ill. ‘By working dying people into his act,’ she wrote, ‘Jones has put himself beyond the reach of criticism. I think of him as literally undiscussable.’ Croce also elaborated on a further ‘category of undiscussability’ which involves ‘those dancers I’m forced to feel sorry for because of the way they present themselves: as dissed blacks, abused women or disenfranchised homosexuals – as performers, in short, who make out of victimhood victim art.’

‘Victim art’ was not Croce’s own term, but it became associated with her, and with the furore around her article. The undiscussion was itself endlessly discussed. Jones’ production became a rallying cry for writers and artists – playwright Tony Kushner and novelist Joyce Carol Oates among the most prominent – while cultural critic Susan Sontag defended Croce, deploring that ‘audiences have become so corrupted by largely sentimental claims.’ The participants in the controversy may regret that it has defined their reputations. Jones himself, discussing it in 2005, admitted ‘I had never been so undone.’ Years after the event, he could still not refer to Croce by name, as she had tried ‘to put a mark through my name in history.’

Filth and glory

Two decades on, where we choose to look is still a question with teeth. Artists and performers who share their traumas, bring their compromised personal histories to the table – those Croce might have described as ‘victims’ – are in evidence throughout both elite and popular culture. Since the Still/Here hullaballoo, reality television has showed us people rutting and rowing, sobbing and shopping, in birth and dying and embarrassing illnesses. Misery memoir has scrabbled through the leavings of abusive childhood and misbegotten marriage. Even ballet now shares its tantrums and tiaras via confessional biography and reality tv (including Agony and Ecstasy about English National Ballet and Breaking Pointe with Salt Lake City’s Ballet West).

In the gallery, Tracy Emin over-shares in the name of art. She stitched the name of every one she ever slept with inside a tent, its moist-breath interior a fug of intimacy. She made her bed a messy memorial, refusing to be shamed by sluttish detritus. Less confessionally, Marina Abramovic and Tilda Swinton offered themselves to scrutiny, placed in atrium or vitrine like a voyeur’s delight. Cindy Sherman and Ryan Trecartin perform masquerades of shifting identity.

Offstage, online, the biggest thing to have happened since 1994 is of course the internet. It is a vehicle for intense self-scrutiny and the widest possible sharing. In a way that has become commonplace, we both invade our own privacy without thought and turn it over to corporations. Our likes, whims and desires – or at least our browsing history – are commodities to be shared and sold. Just as the template of celebrity has morphed from silver screen untouchable into a monster of publicised privacy, so netizens form an online persona that leaches between projection and flesh-bound reality.

Dance theatre too occupies this soul-baring territory. ‘I am not interested in making work that doesn’t not focus clearly on content,’ declared Lloyd Newson, DV8’s artistic director, in 1998. ‘Issues, rather than “prettiness” or aesthetics, are important.’ He has prompted audiences to look at cottaging chaps (MSM), disabled and elderly bodies (Bound to Please), people whose desires run counter to their faith (To Be Straight With You). John, the company’s current production, mined interviews with over 50 men about their experience of addiction, crime, unsafe sex and sauna shenanigans.

More explicitly still, in works like Wolf and vsprs, Alain Platel of Belgium’s Les Ballets C de la B has ushered outcasts onto the stage – broken communities of asylum inmates, delinquent children, dogs and derelicts. ‘Losers in a world of winners,’ in German critic Renate Klett’s words, they disrupt aesthetic sheen in what she describes as ‘Platel’s universe of filth and glory.’ Trained in remedial education, Platel believes his work’s social purpose is indivisible from its artistic credo – he isn’t so much revelling in victimhood, as repairing it, or simply asking us to recognise it within our culture and within ourselves.

Such companies often begin work with research among socially and culturally disadvantaged communities. Others place marginalised artists at their centre: like Britain’s Candoco, which integrates disabled and non-disabled dancers, Fallen Angels (working with recovering addicts, often former prisoners) or the performers with learning disabilities in Theater HORA (the Swiss company collaborated with Jérôme Bel on Disabled Theatre in 2012). Australia’s Back to Back Theatre, an ensemble of actors with disabilities, brought Ganesh Versus the Third Reich to the Edinburgh International Festival last summer; they say the piece ‘invites us to examine who has the right to tell a story and who has the right to be heard.’

A body is never just a body

Dance has often offered the vision of a timeless ideal of the dancing body: in classical ballet, a distillation of grace (the ‘more perfect, or divine image’ that dance historian Jennifer Homans evokes in Apollo’s Angels); the gravid icon of impartial movement in modern dance from Graham to Cunningham. Dancers in both genres gain potency from leaving the world behind. Rising above the stench of quotidian reality is what makes them artists, icons of the impersonal. Yet claiming to be above ideology is an ideology in itself, and one which will often reinforce rather than question privilege.

A body is never just a body. However pure the dancer’s line, those limbs have a history, the blood sings with electric currents of need. Few can stash their frailty in Dorian Gray’s attic – our bodies record experience in every line and bruise, every ache and pulse. From saucy charismatic Marie Taglioni, the first Sylphide, through to Nureyev’s pantherine debauchery, via Balanchine’s fraught muses, even the most radiant stage presence carries a sump of murky mortality. In the audience, we respond not only to immaculate technique, but to a history, locked in flesh.

A visit to Bedlam

How do the powerful gaze at the powerless? Croce makes the undiscussable victims encroaching on the dance stage seem haplessly exposed to contempt or compassion. But what kind of regard is this? For a telling example of victim made spectacle, we should revisit London’s notorious Bethlehem Hospital, popularly known as Bedlam, where the insane and distressed were on display after it moved to a magnificent purpose-built building in Moorfields in 1676. ‘In Bedlam,’ Jenny Uglow writes in her biography of Hogarth, ‘the most awful thing is that this private horror is also a public spectacle.’

In Hogarth’s series A Rake’s Progress (1735), Tom Rakewell’s dissolute career ends in this squalid asylum, his wits and fortune long gone. He sprawls manacled on the bare floor, surrounded by the desperate and delusional. Visitors smirk and whisper behind a fan. The poet William Cowper, recalling childhood visits, admitted that ‘the madness of some of them had such a humorous air, and displayed itself in so many whimsical freaks, that it was impossible not to be entertained, at the same time that I was angry with myself for being so.’ He rightly expresses unease, because Tom and his kind didn’t choose to be displayed. That’s the great indignity of Bedlam, which eventually closed its doors to visitors in 1770, and returns us to the question of who chooses to look, and to be seen.

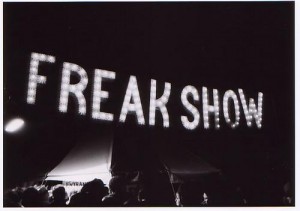

Freak or artist?

If victim art isn’t quite a visit to Bedlam, is it an echo of the freak show? It’s salutary to recall that much of what became high-art dance began rubbing shoulders with all manner of turns on variety bills. Even Anna Pavlova starred in the 1915 New York revue Hip-Hip-Hooray, alongside Toto the clown and an iceskater called Charlotte. Dance was just one more freakish endeavour leading the rush for a buck and a general audience.

Croce’s pointed reference to Jones incorporating the dying into ‘his act’ implicitly makes him a freak show huckster, peddling sensation. Yet the freak show plays a vital role in the history of performance. A staple of British variety and American vaudeville, its audiences goggled at the Boneless Wonder, the Monoped Dancer or the Only Clock-Eyed Lady in the World. Some acts resulted from extreme medical conditions: Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy suffered from hypertrichosis, and Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, from multiple neurofibromatosis.

This isn’t merely a chronicle of barbarity; Merrick was tormented by his display in Whitechapel, but other performers used their parameters as the basis for ingenious and affecting performance. Croce frames the ill as other, yet the suffering body is not necessarily a passive one. The conjoined Hilton Twins, for example, were stars of both the vaudeville circuit and Tod Browning’s still astonishing film Freaks (1932), along with pinhead and bearded lady. Browning insists that these performers are not victims but artists, actively parlaying their bodies into spectacle. We may choose not to look – but we can’t assume that ‘victims’ wouldn’t insist on our attention, and that they aren’t creatively engaged in performance.

Look, and look clearly

Freak is a loaded word, of course. It was telling that Theatre HORA’s Disabled Theatre ends with the learning-disabled performers reflecting on the project – and more than one mentions that, though they had had a blast, creating and performing, their families were often less enthusiastic: several used the phrase ‘freakshow.’ It’s impossible to deny that traditional freakshows trawl for prurience: it lies behind the headlines caused by the film star Bradley Cooper playing Merrick in The Elephant Man on Broadway: one kind of freak playing another. Equally, Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story has settled in a freakshow setting for its latest season of gleeful gothic – British performance artist Mat Fraser joins the cast as ‘Paul the Illustrated Seal Boy’.

In a previous age, disabled dancers might have had to present themselves as ‘freaks’ to build a career. We no longer need to regard different bodies as beyond the scope of art. To take just one example, Australian poet and critic Alison Croggan describes Back to Back Theatre as ‘one of the most groundbreaking companies now working in Australia’ precisely because ‘one of the things they challenge, directly and devastatingly, is that idea that they can’t be taken seriously because they are disabled, which is the implication behind the idea that pity disables criticism.’ They want us to look, and look clearly – not misted by complacent sympathy or distaste.

Can art not discuss race, gender and sexuality, except through Croce’s caricatured categories? Must it define itself as transcending the sprawling world and its cacophony of identities and ideologies? Circling the wagons to protect what you see as art and to exclude the barbarian inadequacy beyond, is tempting – some critics would define it as a necessary part of their function – but we all see art in different places. Some find the performers in Bausch, Platel or DV8 unrefined, guileless products of their own therapy. Their performances may register as artless. But if classical ballet makes the extraordinary appear effortless, the sleight of hand in recent performances is to make the artful seem authentic.

This is easiest to chart in Pina Bausch (named by Croce as one of the ‘undiscussable’ proponents of victim art). Bausch’s formerly unpalatable pieces have now become heritage, performed by second- and third-generation casts of dancers. Some of the material may have been produced by introspective excavation of personal histories, but the current Wuppertal dancers must approach them as demanding texts from a previous age. Even the apparently confessional monologues which stipple her works are revealed in revival as precise script rather than primal screams, as painstakingly constructed as a Shakespeare soliloquy or Petipa variation, and just as difficult to deliver with conviction. The works themselves are extended ensemble pieces – but the lap of repletion and reprise in a piece like 1980 displays a meticulous sense of composition – designed rather allowed to dribble over the stage.

Twenty years after the infamous ‘victim art’ article, it is time to push more heavily on the art than the victimhood. And we need to remind ourselves that the history of performance is in no small measure a history of looking – and of looking away. Looking is a choice.

I also wrote about the 20th anniversary of the victim art controversy for the Guardian, speaking to artists from Candoco, DV8 and Fallen Angels. That article is here.

Follow David on Twitter at @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply