What happens when an artist outlives their own era? When a voice, once so urgent, seems out of time, flailing for connection? Yuri Lyubimov, the great Russian director who died earlier this month aged 97, was a theatrical lightning conductor during the icy Soviet years, gathering the implacable forces of the state and zapping them back in provokingly surreal and thrilling ways. His theatre in Moscow was an unofficial oppositional force – until exile and, just as damagingly, acceptance seemed to interfere with a voice that had for decades spoken truth to power.

Lyubimov’s Hamlet (1971) was one of the iconic Shakespeare productions of the mid-20th century. A largely bare stage was dominated by an immense, pivoting curtain, roughly woven in wool and hemp. It sheltered eavesdropping apparatchiks, swept people from the stage, engulfed the innocent. The poet and singer Vladimir Vysotsky, in the title role, voiced the impotent, bitter distress of his generation. Like so many of Lyubimov’s productions, Hamlet was given force by the need to find an indirect approach to highly charged political and ethical questions.

The tumult of Russian history formed a remarkable talent. Born in the year of the October Revolution, Lyubimov grew up in a culture-loving mercantile family. Both parents were imprisoned during his childhood, and the young Lyubimov brought them sugar and dried bread in prison, banging on the gates until he gained admittance (‘I was toughened up early’).

He trained as an actor, serving during the war in the NKVD song and dance company alongside Shostakovich, performing for officers at the front (duelling in Romeo and Juliet, his blade snapped and almost struck Boris Pasternak in the audience). He came late to directing, in part through teaching at the Vakhtangov Theatre school which culminated in a striking production of The Good Person of Szechwan (1963): Brecht’s epic theatre offered an alternative to the dominant mode of what he saw as ‘boring, gibberish’ socialist realism. Appointed to lead the small Taganka Thetare, outside central Moscow, in 1964 during the Khrushchev thaw, he arrived with a troupe of former students to create a repertoire of audacious productions whose poetic, unabashed theatricality carried an implicit political force.

The troupe’s early productions were agitated montages of a society in ferment (notably John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World, in which the audience was greeted by actors dressed as soldiers from the 1917 revolution); during the 1970s, he produced tragedies of individuals at odds with their society. Lyubimov’s dance with authority in post-Stalinist Russia was close and unpredictable. The threat of censorship was real, and frequently dismaying – a number of productions were banned, others (including Dostoevsky’s The Devils, Pushkin’s Boris Godunov and a memorial to Vysotsky) were refused permission despite prolonged attempts to win approval. Maria Shevstova calls this process ‘trench warfare’ – Lyubimov, she argues, developed ‘ruses and wiles’ in order to achieve ‘a type of covert glasnost.’

One such ruse was a focus on classic texts rather than new plays, often in Lyubimov’s own adaptation (his friend, the dramatist Nikolai Erdman, described him as the Taganka’s resident playwright). Hamlet was accompanied by similarly subversive works: Molière’s Tartuffe (1969), in which characters stepped down from their own portraits, and The Master and Margarita (1977), produced although the full text of Bulgakov’s novel was still officially prohibited. Lyubimov dismissed the clutter of realistic scenery and make up (‘most often nonsensical and quite repulsive’); his theatre lived through music, design, imaginative chiaroscuro lighting and choreography as much as text, achieving a disruptive, fragmentary collage. At its best, the speedy synthesis was both dazzling and powerful – Michael Billington described The Master and Margarita as ‘a breathtaking Meyerholdian production that I would rank amongst the theatrical experiences of a lifetime.’

The dominant images, especially in Borovsky’s designs, burned with concentrated force. A giant pendulum suspended over the stage in Rush Hour; giant alphabet blocks in Listen!; the door to the flat where Raskolnikov commits murder in Crime and Punishment, moving around as if in his waking nightmare. An autocratic and tempestuous figure, Lyubimov manoeuvred his actors like a choreographer, demonstrating precise gestures and intonations, and rehearsed numerous variations of particular scenes (including 17 versions of Hamlet’s encounter with his father’s ghost). He even signalled with a coloured flashlight during performances (red was bad; green was good; white suggested something needed work). Even so, his actors were noted for their dynamic relationship with an eager, questioning audience, who craved a locus of independent thought and covert dissent. ‘Nobody,’ wrote Nick Worrall, ‘will ever forget emerging from the tiny theatre off Taganka Square feeling that this is what theatre is all about.’

Speaking covertly paradoxically allowed Lyubimov to speak to his contemporaries with audacious force. Billington, visiting Moscow in 1983, reported a throng of over 300 young people outside the Taganka, hoping for returned tickets. But that same year, in London, Lyubimov publicly criticised the ban on his productions of Boris Godunov and VV. Retaliation was swift – he was stripped of citizenship, and although his productions continued to be played, his name was removed from posters and programmes.

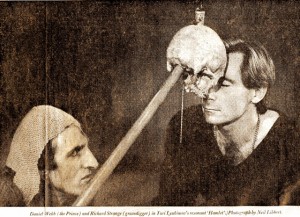

Lyubimov accepted an Israeli passport and did not lack offers of work. In Britain during the 1980s, Crime and Punishment (with Michael Pennington as Raskalnikov) was followed by The Possessed with Harriet Walter and a retread of Hamlet with Danny Webb. However talented the collaborators, they couldn’t reproduce the crackle of his own ensemble and its highly-charged, coded theatrical language.

International opera was also inviting, and Lyubimov’s expressionist productions included Boris Godunov at La Scala, and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and Jenufa at Covent Garden. His designer on Tristan and Isolde in Bolgona (1983), Stefanos Laziridis, marvelled, ‘it was like moving house, because I suddenly discovered all the things I did not really need on stage.’

Having spent years negotiating disapproval at home, Lyubimov didn’t always find creative freedom across the iron curtain. A projected Ring cycle for Covent Garden was abandoned after the opening Rheingold was dismissed as old-fashioned, while Rigoletto for Florence in 1984 caused a furore. Lyubimov and Lazaridis made the duke’s jester a collaborator in a vicious state; the warehouse set was crammed with dummies dressed as clowns and dictators (Hitler, Stalin, Mao), The conductor, Giuseppe Sinopoli, walked before rehearsals began; Piero Capuccilli withdrew from the title role before opening night.

In 1989, his citizenship was restored, but his return proved a curiously deflating triumph. Lyubimov’s best work was produced under the pressure of dark times – under glasnost, its fervour melted (one of his actors became Gorbachev’s minister of culture). In 1989 he directed The Suicide, Erdman’s previously banned tragicomedy, demanding that the cast act as if they might be closed down at any minute, but urgency was impossible to manufacture. Even Dr Zhivago, from the once contentious Pasternak novel, passed without scandal. ‘The audience now sits rather as though it had been hit in the head with a bag of dirt,’ he lamented.

If new freedoms stripped his theatrical language of some of its force, so did a baffling new materialism. The appeal of his theatre had always been as much spiritual as political, a candle glowing in the darkness, and this element now became yet more pronounced, frequently heightened by emotive music. He marked his 80th birthday with an adaptation of The Brothers Karamazov, and The Master and Margarita achieved its 1000th performance in 2002. By 1993, his declawed status was confirmed when the Taganka Theatre was divided into two companies, and a deteriorating relationship with the actors prompted his resignation from the Taganka in 2011; earlier that year he had grumbled ‘working here was never great fun, and now it’s simply impossible.’ He had kept the faith, yet to some it seemed, as critic Anatoly Smeliansky sighed, that ‘the once glorious, the real Taganka, had faded and died with the period in which it was born.’

Main photo via Ria Novosti. Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply