Medea is back, and it grips like a mastiff. No ancient tragedy feels more modern, despite its extremity: maternal infanticide and divine reclamation. NT Live sends its tightly-wound new production into cinemas this evening.

How to account for a classic that clings? On the Paris Review website recently, Joseph Luzzi contrasted the currency of two 19th century Italian novels: Manzoni’s The Betrothed, once hailed as an imperishable epic, and Collodi’s Pinocchio, a children’s book that is still read and studied far beyond Italy. He suggests that Manzoni’s Christian determinism has worn less well than Pinocchio’s fraught journey through childhood, a journey which we all attempt, and which gives it greater universality. ‘The classic that keeps on being read,’ he argues, ‘is the book whose situations and themes remain relevant over time.’

Well, kinda. Sure, we all trudge towards adulthood, with varying degrees of success; but it is only in recent decades that children’s fiction has achieved cultural respectability: scholarly editions, curriculum status, adult acceptability. Childhood and its discontents is a territory of such increasing social and cultural anxiety that fictional works which address the subject have an added charge. Alongside, adults read children’s books without shame (thank you, JK Rowling): commerce and culture are making out. Pinocchio is still read not because it is universal, but because it is universal enough for this moment. That moment may end, or perhaps mutate.

Luzzi is more convincing when he talks, rather beautifully, of works that ‘read us as much as we read them, by revealing what is most important to our lives individually and our age collectively.’ A classic with currency takes a long hard look at its reader or spectator and finds dread and desire it can work with.

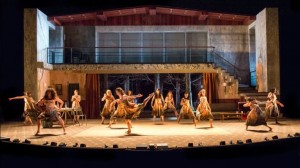

How universal is Medea? It probably depends on your universe. Carrie Cracknell’s production certainly has a feverish power – I sat in the second row on the edge of a panic attack, my chest tight, my breathing shallow. Movement director Lucy Guerin must take the credit for this jiggling unease: Helen McCrory and her chorus (a watchful throng in print frocks, ladies out of Pina Bausch and Katie Mitchell) move with tremors, shudders, thrumming discomfort, sending waves of palpitating reaction into the audience. Wonderfully designed by Tom Scutt, the set defines three different spaces – the swank wedding receotion, Medea’s not-smart apartment, the nightmare woods beyond – into all of which atrocity gradually seeps.

Medea’s particular anguish isn’t mine. I’m not a parent in extremis or an exile waiting to happen. Though who doesn’t often feel a bereft, panicky alienation, a bleary distress at a world without signposts? Or wonder what makes proper parenting, proper love, a sense of the foreign or of home?

These aren’t concerns of all time, all place. The only other Medea to leave a lasting impression on me was Fiona Shaw – like McCrory, a figure of desperate wit, but also a victim of the affluent having-it-all years, turning her Sabbatier comedy upon herself. McCrory is buzzsaw sardonic. She furiously keeps defying our grasp: you may gaze into the actor’s huge, mascara-smeared eyes but not read her thoughts, because she imagines the barely imaginable. With her director, McCrory doesn’t frame the character for sympathy, or understanding. She reclaims Medea’s dark places, the den she scrabbled into, ever deeper, until she doesn’t, can’t, emerge. That harsh particularity, in an age of over-sharing, may be the most compulsive aspect of an immense performance.

What did the original Athenian audience – mostly male, mostly privileged – make of Medea? Did they see their deepest terrors, or feel a secret thrill as the house crashed down about their ears? Did they see loss or possibility? Do we? Medea thrills us even as she scares us, and perhaps that’s her ‘universal’ challenge. Can we go where she goes? Should we even try?

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply