I’ve been fretting about memory this summer. How fragile it is. A snapped synapse, a broken connection, and it’s as if a shelf of books and photo albums has fallen away, leaving only a phantom sense of loss. Cultural memory is equally vulnerable. There is something so haunting in the notion of what survives. Wisps of endurance swirling through the tempest of history.

It’s mind boggling to imagine what has been lost, the sheer random nature of survival. Take classical Greek tragedy, which remains the bedrock of the repertoire (Medea has just opened at the National Theatre). But these plays revered as the keystones of western literature – the Oresteia, Oedipus Rex, Bacchae – have survived by happenstance, while others have vanished or left only odd lines. They were not even the tragedians’ best known, best loved works. In her survey of Greek Tragedy, Edith Hall notes that the mighty tragedians were famed for Niobe (Aeschylus), Tereus (Sophocles) or Telephus and Andromeda (Euripides), all lost. After all this time, turns out we value them for the wrong plays.

Who knows what else has been lost? And is the real question not what survives, but what succeeding generations make of it? Hall describes the fragments of antique tragedy as ‘a tiny textual window on a multimedial ancient event; a few words hacked out of both their performance environment and their literary context to speak – sometimes eloquently – across the centuries.’ They resonate even in their trauma.

As several fine writers have observed, London’s most discussed plays in recent weeks have concerned the way stories survive, and what we need from them. Idomeneus by Roland Schimmelpfennig plays like notes towards a lost Greek tragedy, assembled from splinters scudding through the collective memory. Classical myth marinates in a bucket of poor life choices: Idomeneus secured his safe return from Troy by vowing to sacrifice the first creature he encountered on shore. Cue a welcome from his son. Schimmelpfennig makes a canny choice of story; although woven into the fallout from Troy, the ethical murk of competing loyalties, there’s no extant tragedy on the theme. Mozart’s solemn opera is the most lasting treatment.

In Ellen McDougall’s teasingly fine production at the Gate, everyone is chorus – her five actors narrate, enact, dispute the story. They begin politely, hovering at the edges of a glossy set; during the ensuing hour they increasingly plumb storylines of splatterfest retribution, hornbucket fantasy, bereft and lurid versions of the story that ripple far from the original premise.

What would the Athenians make of it? Without the music, the masks, the web of civic structures in which ancient tragedy was created? Our versions of classical tragedy, Shakespeare, even My Fair Lady are as far as the wine dark sea from the resonance each work might have had for its original audience. We take what we need from the past; or, beachcombing, we salvage what we can and use it how we need.

Anne Washburn’s jaw-dropping Mr Burns – performed with fretful vim in Robert Icke’s production for the Almeida Theatre – shows a traumatised society grabbing a single pearl from the cultural wreckage. Could have been Shakespeare or Hitchcock, but instead it’s Groening. Not even a box set of plenitude but a single half-hour episode. Cape Feare is a classic slice of Simpsons irreverence – tripping up canonised culture (Scorsese, Gilbert and Sullivan), gobbing in its ear, running with it to create something new-minted.

Why this story? Because it’s there. Lodged, more or less, in everyone’s head. In a time of trauma, freighted with miserable significance, it’s a reminder of ‘meaningless entertainment’, even if people are too apprehensive or battered to express delight. The survivors in Washburn’s first act stumblingly reconstruct the episode – the pleasure is in remembering something that isn’t this irredeemable present.

We see the survivors working the episode up into a touring theatre act – people fall ravenously on memories of The Simpsons – while in Washburn’s final act, set in a distant future, the familiar cartoon has been repurposed into a dizzyingly rich and strange opera-cum-ritual. It’s like an Oberammergau yet to come. The strangeness is amplified because we don’t see how the audience receives it: with awe, delight, derision? We can only imagine what they take from it, why they need it.

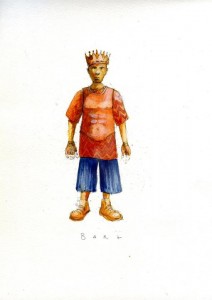

It’s a marvellous text of scraps and mutant fragments. Throughout, you catch snatches of Danny Elfman’s skeetering Simpsons theme tune, its glee turned into sacrament. A cartoon is without consequence – almost 26 years and over 550 episodes in, and the Simpsons remain as blessedly unimproved a family as America can offer. Each episode, as the title sequence demonstrates, resets the family to zero. However, in the future Washburn imagines, every irreverent throwaway detail has become laden with meaning. Bart, a character without conscience, is niw the emotional fulcrum of an epic endeavour, bravely asserting the value of human life. Amid a dizzying range of textual, musical and design references, It’s nice that Bart’s poopdeck confrontation with Sideshow Bob – played as a lordly Captain Hook figure – recalls Peter Pan, another adventure story that mutated into a mawkish theatrical ritual.

The Simpsonites of the future create a dazzlingly strange new culture out of their fragments. It’s a beautiful, baffling thing. And, as our fallible rustbucket memories fumble their connections, it’s what we all do. Take the fallout from that great loss, the destruction of the great library of Alexandria which snatched from posterity a huge swathe of antique literature, including countless Greek tragedies. ‘How can we sleep for grief?’ exclaims Tom Stoppard’s young heroine in Arcadia, aghast at the loss. ‘By counting our stock,’ replies her tutor. ‘We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind.’

Follow David: @mrdavidjays

[…] Published 2014-07-24 Managing expectations AJBlog: Sandow | Published 2014-07-24 Survivor stories AJBlog: Performance Monkey | Published 2014-07-24 What is Creative Placemaking? AJBlog: Field […]