The challenge with basing a ballet on Shakespeare isn’t, oddly, watching the words fall away. That’s a given. It’s how you mine the silences, the telling moments in which ambiguities cluster and on which the story turns. Christopher Wheeldon’s fascinating new ballet (for the Royal Ballet and the National Ballet of Canada) of The Winter’s Tale – the first recorded of that brilliantly strange late play – has frustrations but often responds in intensely ways to a story which turns on what isn’t clear, which gallops or soars leaving prosaic in its wake.

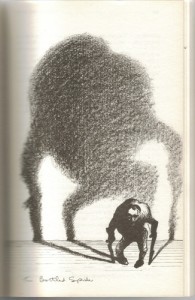

Actors’ bodies attempt to fall in line with their mouths, but dancers can embody metaphor without embarrassment. When Antony Sher seized on the image of Richard III as a ‘bottled spider’, he memorably deployed crutches, a roiling prosthetic back, looming shadows. Edward Watson portrays Leontes’ unforeseen spiral into the irrational without accessories. Without warning the king becomes convinced that he’s a cuckold, and compares this ‘knowledge’ to an envenomed spider lurking in his drink – ‘I have drunk, and seen the spider.’ In Watson’s version, his madly capering hand, fingers ascuttle, takes on a life of its own, spreads infected jitters through his body like a toxin through the bloodstream. His body becomes a stranger to itself – his fists pummel his head, his feet paw the floor like hooves, something inhuman possesses him.

Important wordless things that happen in this play – such as whatever unspoken thing tips Leontes over the edge. Shakespeare offers a bald stage direction (Hermione ‘takes Polixenes’ hand’) and suddenly the king husband is all, ‘Too hot, too hot!’ Wheeldon (pictured top in rehearsal by Johan Persson) finds a moment of potent intimacy – as Hermione’s baby kicks, and she presses first her husband’s hand, then his friend’s, to her belly.

When I interviewed Lauren Cuthbertson during rehearsals last month, the moment was slightly, but crucially, different. ‘We’ve all been dancing together,’ she explained, ‘and I feel the baby kick. I turn to Polixenes, just because I happen to be at that angle, and say, “Oh, feel the kick.” Then I say it to Leontes – suddenly there’s a freeze, and you see what’s going on in his mind.’ The reversal means that there’s no ambiguity about her intention – but the picture of the two men, each pressing a palm on the heavily pregnant belly, is compact with an uneasy intimacy. It suggests what Raphael Lyne, in his study of Shakespeare’s late work, describes as ‘spare energy’ – often in a sexual context – that spills over the romances, giving moments such as this a ‘disproportionate intensity.’

Zenaida Yanowsky finds something equally powerful in Paulina, the abused queen’s dauntless defender. There’s a comic note in what I often think is my very favourite Shakespeare character – she nags on the side of the righteous – which the ballet doesn’t attempt. But there’s also a sacramental force in this woman who gathers the tale’s unknotting into her keeping – ushering the fallen Hermione away, keeping her hidden for 16 years, stoking and soothing Leontes’ remorse until she is ready to reunite them. There’s a realistic explanation to her rough magic, but such behaviour leaves naturalism far behind (‘It is required/ You do awake your faith’) – in this semi-pagan theology, Paulina takes on a priestly air, which Yanowksy rives into her body from the beginning. Her albatross arms beat with sorrow and resolve; she arches her back and lurches forward as if burdened by mysteries which she will only gradually reveal.

These are things that a performance of the play would struggle to match. There are other things that Wheeldon doesn’t manage. Perhaps he didn’t have time – making a vast new ballet, without the benefit of theatrical previews – or simply he didn’t see them. His courtly first-act corps de ballet is not just dull but uncharacterised. What kind of regime is this? A formal court on the brink of tyranny? A cosy household unprepared for disaster? I love the quote (where does it come from?) that playing a king does not depend on how the monarch behaves, but on how everyone else treats him. These wafting couples don’t treat Watson like a ruler, but like a ballet principal – decorously getting out of his way, filling in the background. Only Yanowksy invests him with authority – when she raises an indignant hand, remembers who he is and drops into a reluctant curtsey (later she won’t hold back, and we register the shift).

A bardhead should probably be barred from Shakespeare ballet. The urge to lament lost moments is too strong. I truly regretted the rushed end to Act One: not simply an underwhelming bear from puppeteer Basil Twist, but more the shepherd’s too-brief discovery of the baby (here, a creepy animatronic doll waving its waxen limbs). You need a moment to register that the story’s course is turning from disaster to repair – a beat equivalent to the shepherd’s line, which slays me every time, ‘Thou met’st with things dying, I with things newborn.’ Frozen hope begins to run again.

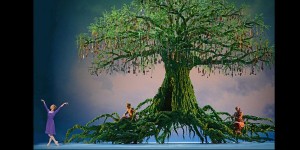

Wheeldon’s second act (act four of the play) is the most successful as ballet. Indeed, it’s pretty much a triumph. It’s the Bohemian sheep-shearing festival, which Bob Crowley sets around a vast and gloriously verdant tree – burstingly green from topmost branch to root, and hung with the community’s glinting tokens. Joby Talbot’s music here is richly unexpected, an invented folk tradition. As he explains in a programme interview, he assembles a ‘broken consort’ of ‘a bansuri (a type of Indian flute), dulcimer, accordion and some exotic percussion instruments.’ The score has rich, shadowy texture, as well as rambunctious energy, and lets the dancers wheel and leap. The opening moments – in which Sarah Lamb’s Perdita dances in solitary gravity to a haunting bansuri melody (feelingly played by Eliza Marshall), while Steven McRae’s besotted Prince Florizel watches from afar – form surely the most beautiful single scene in recent ballet. Time holds its breath and quivers with delight.

One character is decisively silenced in this version – Autolycus the travelling scam-artist, who fleeces everyone at the shearing. Wheeldon cuts him altogether – but his quick-thinking momentum remains in Florizel, who gets to be a more decisive, less entitled prince than usual, while his unscrupulous manoeuvres inform the score’s dark places.

Wheeldon’s last act returns us to Leontes’ court – where the grieving king nestles his head in Paulina’s hands, entreating her to carry his skull full of sorrows. The play’s final silence – one which most directors ignore, and only a few mine for discomfort – is Hermione’s. When she is revealed as alive, she speaks just once, to her newfound daughter. Her husband is effusive, but she says nothing to him. Wheeldon gives the couple a pas de deux, while everyone else sidles out to allow them some privacy, but he doesn’t quite nail why. Is harmony restored? Will scar tissue mar their marriage? In any event, when everyone returns, Hermione focuses on Perdita, and mother and daughter leave together. Paulina has to usher Leontes out after them, and may get her wish (denied her in the play) to lament her own losses like an aged turtle dove on a withered bough, ‘till I am lost.’

I left the ballet unresolved – torn between its insights and its absences. 24 hours on, I’m still thinking about it – wanting to see it again, hoping to see it grow.

The Winter’s Tale is at the Royal Opera House, London until 1 May, and will also be screened in cinemas.

Follow David at @mrdavidjays

This is the best most eloquent interlectual review yet!

It’s less about the dancers and how they interpret and more about how the play translates.

Could you give us your thoughts on how the dancers actually performed as your opinion would be valued.

Magda, thank you for the very kind comment. You are never sure how much the impact of a new ballet is due to the individual interpretations, so I will be interested to read about the Royal Ballet’s second cast. The opening night dancers seemed well cast – Edward Watson pushed Leontes’ twisty, torturous body language; Lauren Cuthbertson retained immense dignity as Hermione, especially in their dance ‘argument’. If their final pas de deux was less involving, that may be because the choreography was less developed. Zenaida Yanowsky’s Paulina was eloquently danced – while the second act took fire from Sarah Lamb’s sweetly serious Perdita and Steven McRae’s buoyant Florizel (plus the exuberant Valentino Zucchetti). If the ballet remains in the Royal’s repertoire, it will be fascinating to see how other dancers inhabit those roles.

Will you be seeing the ballet, either live or in the cinema? If so, do let us know what you think.