Polite. Agreeable. Well-behaved. These are not terms that should come to mind when you evoke the seamy edges of Jacobean drama, but they were the impression left by The Malcontent, John Martson’s swingeing tragic-comedy, originally written for a company of child actors, and now revived by Shakespeare’s Globe Young Players.

Marston was 26 at the play’s premiere. He was enmeshed in the combative, scurrilous, authority-tweaking world of wits who were reared in the law and swaggered at the theatre. Marston was a gratifyingly wild child and a trial to his lawyer father, who despaired when John failed to follow in his professional footsteps. Dad even left son a pointed legacy of his law books – a draft version of the will said tartly that they were going to ‘him that deserveth them not, that is my wilful disobedient son, who I think will sell them rather than use them.’

It says something that a man like Marston and his involved, spiky plays suited the repertoire of the children’s companies. These are the ‘little eyases’ – nests of young hawks – that Rosencrantz tells Hamlet are stealing all the best gigs from the adult troupes and winning fashionable audiences. Shakespeare didn’t write for them, but many others did, including Jonson, Chapman, Beaumont and Fletcher (Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, previously at the Wanamaker, was also performed by a children’s company).

What would it have been like to see these original actors? Ben Jonson’s comedy Cynthia’s Revels gives some idea – in the play Mercury and Cupid disguise themselves as page boys, and say they will ‘act freely, carelessly and capriciously, as if our veins ran with quicksilver, and not utter a phrase but what shall come forth steeped in the very brine of conceit, and sparkle like salt in fire.’ A stage full of smart-talking little dazzlers – no wonder the young hawks were popular.

Lucy Munro’s study of the most enduring company, the Children of the Queen’s Revels, can only hint at the boys’ companies in performance. Lacking contemporary evidence, she constructs a picture from moralists’ attacks and the plays themselves, and explains that ‘children’ is an elastic term – especially as actors grew up with the company, the age range may have stretched from 10 into the early 20s, giving scope for sophisticated writing and performance.

Like the early-modern adult companies, these were all-male ensembles, and critics of the young actors fixed – or rather, fixated – on sex (remember how Graham Greene described the ‘dubious coquetry’ of the young Shirley Temple?). One troupe was described as ‘a nest of boys, able to ravish a man,’ while another claimed that spectators sitting on the stage at an indoor playhouse ‘may (with small cost) purchase the dear acquaintance of the boys.’ It was even rumoured that the dowager countess of Leicester had married a young actor. The plays themselves raise the miasma of troubling or inappropriate desire, especially through cross-dressing characters. Munro highlights the page Lionell in Chapman’s comedy May Day, who turns out to be ‘a woman disguised as a boy disguised as a woman; complicating things further still, this character was originally, of course, played by a boy.’

Highlighting the sexual allure of school-age performers would be – to put it very mildly – uncomfortable these days, but there are less dodgy ways to unsettle an adult audience. There’s a dash of cross-dressing in The Malcontent, too, which is a very adult play – political intrigue, government riddled with corruption, marriage as the merest cover for infidelity, assassination as a legitimate political manoeuvre. Malevole, the malcontent himself, is a deposed duke who disguises himself as a thorn in the side of the court.

It’s adult in matter, but wonderfully adolescent in sensibility – utterly disenchanted, written with eye roll, huffing bad temper, most its characters having the horn or the hump, or both. It should be perfect for a cast of smart, glowering, hormone-surfing young people. Adult audiences might have felt like parents unflatteringly mocked by their merciless teenagers.

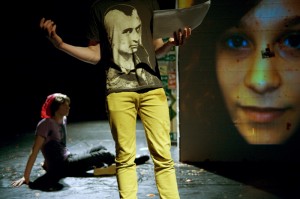

That’s not what we get at the Globe. It’s hard to see how much support the cast of this intrepid first venture at the enchanting Wanamaker Playhouse (all aged 12-16) have received from their director, Caitlin McLeod. The rambunbctious final jig insists on their cheeky energy – but for most of the previous 150 minutes, they recite rather than perform, are nice rather than entertainingly obnoxious. There’s no wit, no swagger. We can’t expect the alarming assurance of Jodie Foster’s nightclub siren in Bugsy Malone, but the Globe might look to the confrontational young casts of Belgium’s Ontroerend Goed, who in shows like Once and For All We’re Gonna Tell You Who We Are So Shut Up and Listen are unpredictable in their wit, attack and vulnerability.

Many child performers are required to present the acceptable face of childhood – the intrepid innocence of Harry Potter, the indomitable Little Miss Sunshine, or the endearingly arch Manny in Modern Family. Although casting them as vile adults, the Globe has tamed its young actors rather than released them. Some of them have some admirably intractable moments, but the only person who gives a properly eye-catching performance is Sam Hird, who drags up as the match-making hag Maquerelle. Hird rocks his farthingales, dispenses dating tips, paws a nervous servingman, and with evident dismay is eventually banished to the suburbs. It’s a terrific turn.

An attack of the polites can overtake the best of people. Marston himself, for all his naughty city ways, eventually left London for a career as a clergyman. His father, who wished that John would ‘forgo his delight in plays and vain studies and fooleries,’ would have been delighted to find that his son became a Hampshire clergyman, later preventing his name being attached to an edition of his mucky, scurrilous plays. Any hawk can lose its claws – but surely it deserves a chance to fly.

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

[…] Published 2014-04-22 Institute for Advanced Study AJBlog: Sandow | Published 2014-04-22 Little hawks AJBlog: Performance Monkey | Published 2014-04-22 Small-Frame Vignettes AJBlog: Dancebeat | […]