Friday, January 13, 2012

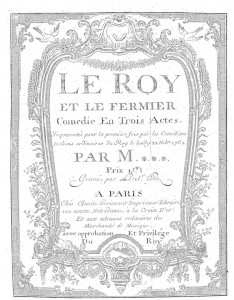

I’ll be spending the weekend in New York City at Chamber Music America’s annual conference. When I’m not playing the harpsichord, I serve as President of the Board of Trustees for this national service organization that tries in every way to make the lives of classical and jazz musicians who play in small groups, workable, acknowledged, sane! There is so much to keep me thinking and on my toes surrounded by people doing important work brilliantly. Clouding my focus however is that Monsigny score on my music desk. If only preparation involved dreaming about Versailles, looking through my old pictures of the chateau and calling up memories or enjoying expectations. There is that score and I have to face the music.

For me, it means going over each measure of the opera and figuring my part. This is a strange image so I’d better explain! The harpsichordist who plays at almost every moment of the opera needs to have a “cheat sheet” of the bass line and a series of figures (numbers) under the bass notes that indicate what harmonies are called for. Often in the 18th century, the composer led from the harpsichord and had no need of clues. After all, he wrote the piece. But I need clues and before I take my place in the orchestra, those figures need to be written in. Now most of the harmonies are simple but we keyboard players need to look over the entire score, the strings, the oboes and flutes, and make sure we are not playing the perfectly WRONG note. I could rely on my ears and work out the figures in the first rehearsal, but I’d rather be more responsible and come on top of the game.

For me, it means going over each measure of the opera and figuring my part. This is a strange image so I’d better explain! The harpsichordist who plays at almost every moment of the opera needs to have a “cheat sheet” of the bass line and a series of figures (numbers) under the bass notes that indicate what harmonies are called for. Often in the 18th century, the composer led from the harpsichord and had no need of clues. After all, he wrote the piece. But I need clues and before I take my place in the orchestra, those figures need to be written in. Now most of the harmonies are simple but we keyboard players need to look over the entire score, the strings, the oboes and flutes, and make sure we are not playing the perfectly WRONG note. I could rely on my ears and work out the figures in the first rehearsal, but I’d rather be more responsible and come on top of the game.

Two of our string section leaders, cellist Loretta O’Sullivan and concertmaster Claire Jolivet have their own obligations to the first rehearsal as well. They have gone through every page, every phrase and every note, not only to know what their fingers need to do, but to bow the parts for the entire string section. The bassoons also rely on these indications. Bowing the parts is important work and central to the success of the performance. What does that mean, bowing all the parts?

When playing a note, you can either run your bow from bottom (frog) to top (tip) or visa versa, from top to bottom. The first motion is known as a down bow, the latter, an up bow. Because of the weighted nature of a violin or cello bow, down bow is usually a stronger gesture and up bow, more delicate and less assertive. In a way, the sounds that result resemble the strong and weak syllables or feet in a poem. Is THIS the FACE that LAUNCHED a THOUSand SHIPS? The caps get down bows. The string section leaders have to go over each phrase and make sure each violinist, violist and cellist is accentuating in the same way, speaking with the same balance. The coordination of the bow movements is much more than visual neatness and this applies across the board from Mahler’s 7th to Suzuki’s Twinkle!

Ryan has arranged several mini performances of excerpts of the opera and much of this work has been done months ago. Stretching the burden out makes it lighter and the string leaders come to the first orchestral rehearsal more than ready to be the leaders of the band. Now let me focus on Chamber Music America.

[…] a van as I usually pack a harpsichord. # But today I’m on a train, thinking I can get some of the figuring work done that I haven’t completed, and I’m thinking about what and who I leave at home for two […]