When the Metropolitan Opera rises to its own standard, no opera house in the world presents more engaging, exciting, or satisfying performances. On November 5 the new production of Alban Berg’s Lulu fulfilled every aspect of the composer’s complicated and difficult work. Anyone who comes to New York during its run should try to attend a performance.

When the Metropolitan Opera rises to its own standard, no opera house in the world presents more engaging, exciting, or satisfying performances. On November 5 the new production of Alban Berg’s Lulu fulfilled every aspect of the composer’s complicated and difficult work. Anyone who comes to New York during its run should try to attend a performance.

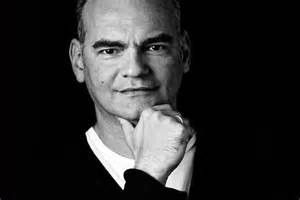

William Kentridge had a signal success a few years ago with Shostakovich’s The Nose, a production that I missed. What he did with Lulu can only be called inspired, but much was expected. The surprise of last night to me came from the brilliant conducting of Lothar Koenigs, a recent replacement for James Levine. I had not had the opportunity to hear Maestro Koenigs conduct before (he is the Music Director of the Welsh National Opera), and his work was revelatory.

Just as Levine in 1974 opened remarkable new aspects to Berg’s Wozzeck (and later to Lulu), Koenigs brought to the work a sensuous, romantic sound that the opera often lacks, while never sugar-coating Berg’s score. The sheer beauty of so many orchestral passages in this opera have never before in my hearing been so moving. Mahler hovered in the wings at the premiere, and the analytical, almost clinical approach favored by many German conductors vanished. The Metropolitan Opera orchestra, one of the world’s greatest, has never sounded more expressive or varicolored. Musical moments occurred that I certainly had never imagined before.

One intriguing aspect illuminated by Koenig’s conducting was the slight difference in the section of Act III composed from Berg’s notes by Friedrich Cerha four decades ago. Just as Suessmayr’s recits in La Clemenza di Tito and Ernst Guiraud’s recitatives in Carmen do not have the brilliance of Mozart or Bizet, this section, though beautifully performed, did not quite have the musical quality of the rest of the opera.

Kentridge’s production, with Luc De Wit as co-director, Sabine Theunissen as set designer, Catherine Meyburgh as projection designer, Greta Goiris as costume designer, and Urs Schoenebaum as lighting designer, told the story, expanded one’s imagination, never failed to fascinate, and made the almost four-hour evening pass in a flash (To indicate how great it was to me, I came to Lulu three hours after arriving from Paris so the performance began at 1 AM on my personal time clock.).

The dynamic stage picture kaleidoscopically portrayed the plot. One great innovation came from the titles. They were displayed on the Met’s normal system, but because the whole opera was played on a slightly elevated platform, they were also flashed on the elevated section, in one act on one side and in the next on the other. These subtitles kept one’s eyes fixed on the amazing goings on. There was a grand piano onstage, first on downstage left, then on downstage right, theoretically played by a young woman who took many varied athletic poses seemingly added for an effect I cannot explain. The back drop, a wall that had many different openings in it was plastered with posters, drawings, and many extraordinarily apt projections. There were also at different times large words, some in German, some in English, projected on the wall. In the second act on stage left the wall opened to reveal a high staircase; in Alwa’s apartment in Act III the confines of his living room were indicated. Nothing was totally specific, but there was never a moment when what one looked at was uninteresting. The coordination of projection and lighting could not have been improved. The costumes were striking. Dr. Schoen was most of the time dressed in a bright green suit, and Lulu wore most of the time wore a white dress, always revealing her shapely legs, sometimes a lot more than others.

Marlis Petersen has created her Lulu in nine other productions, none of which I have attended. But I have heard a fair number of Lulus since my first in Santa Fe in 1964. No one has ever surmounted the incredibly difficult role so accurately and with such ease. Her frequent high notes that can sound like a scream always were hit straight on and accurately. Her Lied had particular emotional weight. Her acting throughout made her character completely believable. Reputedly, this is the last time Petersen will take on the role; anyone who can experience her live should do so.

The whole cast was solid and completely in command of the difficult roles. Daniel Brema in his Met debut as Alwa sang with firm, strong voice, while his father, Dr. Schoen, found the German bass-baritone Johan Reuter an ideal interpreter. He looked right; he acted superbly, and his voice had an ideal color. The role of Lulu’s father, Shigolch, received a properly run-down, lower class realization by Franz Grundheber, and Paul Groves made a believable, extremely well sung Painter, Lulu’s second husband. Everyone in the cast lived up to their roles’ demands, but a particular notice should be given to Elizabeth DeShong, whose diminutive size allowed her visually to portray the School Boy even with her adult voice.

The remarkable Susan Graham enacted the Countess Geschwitz, a crucial though fairly short role. Before I have often seen this Lesbian character played as a caricature of sorts; she played her intensely, with feeling, and with predictable, extraordinary vocal grace.

This was a great night at the Metropolitan Opera, filled with superb singing, a great conductor, and visual magic.

After Kentridge’s brilliant contribution to THE NOSE last season, I was looking forward to seeing what he would do with LULU. Some of his visuals were interesting. But the continuous, often frantic, changes of imagery I found distracting. LULU is excellent theatre with startling music. It was often hard to concentrate on what the people were doing or saying because of the myriad images being flashes before us. Nonetheless, I agree that the singing and conducting was of the highest standard imaginable. I aw LULU ion Santa Fe in the 70s and in Houston around the same time. Houston used enormous projections of appropriate photographs that set the scene without being a distraction. I wish Kentridge had done the same.