The other day one of the excellent character artists in opera wrote me that he was going into another business: he likes to perform in the United States, but many companies, both large and small, have stopped engaging mature performers and were using young artists instead. This could be much more a disaster to opera than it might seem.

Great opera is not cheap, and since the birth of opera in the early 1600s it has needed high quality casting throughout–and generous donors to support it. A classic example, as a matter of fact, is Lucano in Claudio Monteverdi’s Coronation of Poppea, the first truly great opera. He doesn’t have much to do, but he does sing with Nero in one of the most engaging and significant duets early in the opera. Nero is rejoicing over the suicide of his tutor, the philosopher Seneca, and believes that no one now can criticize his pursuit of Poppea. In most productions the duet involves athletic, happy action between the two men; whether that happens or not, it’s very complicated to sing. If less than an experienced, first-class singer and actor is used for Lucano, the duet will not have either the dramatic or vocal importance it deserves.

Some character roles demand mature voices and could easily harm young and still settling voices. Take the five Jews in Salome, four of whom are tenors. Strauss created some of the most difficult small roles in opera for only a few minutes for each because he believed opera would always take place in repertory opera companies where there were plenty of singers who could ideally fill the roles during an eleven-month season. That was the case, certainly in Europe, in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Our current American system in which everyone in the cast is assembled from scratch in almost all of our opera houses never occurred to him. The fact remains: if any one of the Jews can’t handle the difficult vocal line, it harms the whole, and these are parts that should not be sung by developing voices.

In most cases the problem is knowledge of the intricacies of language and the stage, the first a problem with many young Americans, and the second the kind of artistry and command that comes only with experience.

Charles Anthony and friends in 2004 on the 50th anniversary of his Metropolitan Opera debut. Credit Chang W. Lee/The New York Times

A few vivid examples might suffice. Charles Anthony, who filled a wide number of character parts, retired from the Met in 2010 after 56 years and 2928 performances. The unforgettable Alessio de Paolis, who over the course of 26 years from 1938 to 1964 at the Metropolitan made even such very small character roles as Iseppo in La Gioconda memorable. Character women singers don’t have as many roles, but the contribution of Thelma Votipka in her 1422 roles over 31 years from 1935 until 1966 added much to so many operas. Catherine Cook and Dale Travis, both of whom currently singing for San Francisco Opera, have contributed much to that company’s success, and at Seattle Opera over the last seventeen years Doug Jones has created memorable vignettes. Also at Seattle Opera Archie Drake in his last twenty years moved from a lead artist to an invaluable character artist, a vital vocal and dramatic presence until a few days before he died. All of them worked in many other companies as well.

If someone says that the people come to hear the music and the principal singers, that may be what much of the public may think, but the reality is that character artists in many cases create the milieu in which the principals perform.

Take the subtlety of language. Everyone who has any familiarity with

the plot of Tosca knows that Cavaradossi’s death by the firing squad is a shock to Tosca. In the preceding scene Scarpia, in order to have his wicked way with Tosca, calls in Spoleta and tells him that he is changing the death command for Cavaradossi and that her lover will go through a mock execution as did Count Palmieri. Spoleta repeats Scarpia’s words– in Italian, “come Palmieri” or “like Palmieri”–and leaves. At least 75% of any opera audience, maybe more, knows what Tosca doesn’t know–that Palmieri died by a firing squad as will Cavaradossi. The trick is that the artist playing Spoleta must sing the phrase in a way that will not alert Tosca to Scarpia’s duplicity, while conveying to the audience that he knows what Scarpia means. This is not easy, and it takes acting ability, comprehension not only of the words, but the way to respond properly to the Scarpia of this performance.

As for stage savvy, the character actor must instantly be ready to adjust to surprises from the principals. Take this example, which happened not long ago. An Elisabetta in Don Carlo was staged to move upstage as she was singing the farewell to the Countess Aremberg. Her page was rehearsed to exit downstage and in front of where she had been singing. In the premiere the page started to move; the soprano changed her mind, walked into the page’s path, and could have literally collided with the page. Fortunately the page was experienced, saw this coming, and withdrew quickly, moving behind the soprano. No one noticed a thing. One may say from this description, big deal. Not so. A person with very little stage experience and nervous will often do exactly what he or she has been rehearsed to do, devil take the hindmost. And in this case there could have been a collision.

Or take La fanciulla del West, Puccini’s American gold-rush opera. It is literally loaded with character singers–a bartender, a minstrel, a miner who cheats at cards, lots of cowboys who in a good production are made into individuals. Some of them can easily be performed by young artists, but most of them need experienced performers who can form the milieu so crucial to the opera. In other words they must do their parts in such a way that an American audience, very hard to please in this opera, will not see them as opera singers trying to be cowboys, but the real thing.

Many roles, such as Borsa or Marullo in Rigoletto, Valzacchi and Annina in Der Rosenkavalier, the first Prisoner in Fidelio, the Dancing Master in Ariadne auf Naxos, Trabucco in La forza del destino, Falstaff’s cohorts Pistola, Bardolpho, and Dr. Caius, and many other roles demand language and experience. Each of them adds greatly or detracts from a performance.

In some cases young American artists either because of their inherent ability or great coaching can do them well, but many young artists green to the stage and not really knowledgeable in the language of the opera are only ready for these roles if there is extensive coaching and a director who will take time with them, time that is not always available in a three- or even four-week rehearsal period.

In short I am not arguing against ever using young artists in character roles, but if experienced character singers are finding no work and leaving the business because all these parts are given to young artists, the quality of opera performance is injured. What is needed is to continue the American tradition of blending the young and the experienced character artist.

This is a sorry thing that is happening. Comprimarios such as the great Charlie Anthony, Joseph Frank, Anthony Laciura, and so many others have added wonderful color and drama to their roles. This is experience that will not be easily replaced by novices. However, it seems to me that this is not only happening with the “small” roles, but major roles, too. Mature artists are being replaced by younger and less experienced artists because they “look” more the part (and who cares if they can sing it or should sing it!) or because they get paid less.

It must be a nightmare to try to run an opera company in the US these days. But don’t shot yourself in the foot trying to balance craft vs funds.

Amen. I see it happening all over the place. It also belies a certain naiveté and lack of education of the public, as they accept less than what a performance could be, because they hear beautiful music and, not knowing what a mature and experienced artist can do with it, accept a mediocre reading of divine music as if it were divine. …Simply because the music is gorgeous. So you get young artists debuting in huge houses in roles that used to be given to artists who had cut their teeth and learned the ropes in less important theaters. Instead of a real artist finally making his/her debut in a role he/she had already done after years of working up the LAYERS it takes to bring a rich performance in performance after performance, you have a young (telegenic?) singer (not artist) singing pretty arias with a superficiality and banality which impoverishes the entire art form. And yet the music carries the day, so an ignorant public goes home, thinking they have heard the most beautiful thing in the world because they don’t know any better (and the music is gorgeous even if it’s just sung), not knowing it would have been life-changing if they had heard/seen a great artist perform the same thing. It’s great to have a “discovery” of a new artist every now and then, but there has to be SOME experience on that stage!! 🙂

Opera is indeed a team sport, and performers and performances benefit from ‘old pros’, who not only do their jobs superbly, but also inform younger colleagues by example from the minute they come to rehearsal or the dressing room to how they breath or handle themselves onstage. They give conductors and directors deeper material to work with as well. Ours is an aural, oral and kinetic tradition and while great teachers and coaches can do a lot, there is no substitute for the kinetic, imitative experience of being onstage with great and experienced artists, whatever the role.

The Met, San Francisco, Houston and Seattle (in my experience) have been striking the right balance in casting Young Artists or more experienced character actors. Let’s hope these companies and others see the value of both types of performers and give work to all of them.

Loved reading about Archie drake.

Thank you for writing this!!!

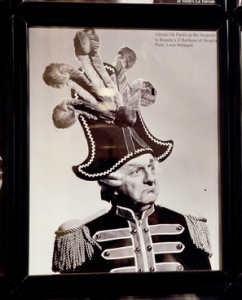

A very interesting article! However, taking nothing away from the illustrious careers of character singers, the photo labeled as character tenor Alessio de Paolis is actually a publicity photo of baritone Martial Singher as Dapertutto. As far as I know, Mr. Singher sang only principal roles during his long career–I played for Mr. Singher in his vocal studio for six years and looked at that photo every day I was in that studio at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, CA!

You are 100% right. I had another photo to use, which will go up immediately. It was a mistake. Thank you for noting it.

Speight Jenkins

Thank you for this important entry. Experience and knowledge of language are invaluable tools for an opera singer. However I fear that money is playing a great role in preventing companies from hiring experienced singers (in comprimario and sometimes leading roles). Some larger North American companies can still afford to hire more experienced singers. But many regional companies simply can’t and will use young artists. I don’t know whether there is a solution for this.

Oh, well said! Sadly, the same is happening in Europe too. I was recently talking to a young singer who admitted that without the sage advice of the older and more experienced members of the cast, he would have utterly wrecked his voice; these are the singers who are being replaced by younger, cheaper artists.

Thank you, Mr. Jenkins, for addressing this vital issue in print! As you are greatly respected in the industry, perhaps people involved in casting will read this and stop to consider the value of mature, experienced singers to a show. We can only hope!

Wonderful article and agree heartily. It is a pleasure when companies can blend the young with the experienced in creative and exciting productions.

But I do have to wonder if these aging singers who can’t get work are refusing to work at smaller companies in smaller roles as time affects all. But that is another article for another time I’m sure…

The whole point of the article and discussion is mainly about character singers, many of whom have been singing this repertoire their entire careers. They are experts in their fields, and are getting sidelined because they’re using young, greenhorn singers to do these roles. I also lament the mature (in the true sense of the word, not some kind of code for “old”) artist being elbowed out and deemed “too old” because the powers that be want someone new and young because they seem to think this is the only way to attract a younger audience. A good mix is always the key. In an art form that relies on SO MANY years of training, it is almost criminal to be rewarding youth over experience. And it does impoverish the art form. I do agree that time affects all, but it used to be a VIRTUE to still sing beautifully after 20+ years of career. Now, nobody really cares. They seem to just want the next voice to chew up and spit out. I find that aspect of the business sad. And I fear that most of it is not even an artistic choice or even an aesthetic choice, but just a financial choice to use the cheapest singer they can get.

^^ Laura said pretty much all I wished to express here. Except speaking as one of those older singers, I don’t know ANYONE who has turned a role down on the grounds that it was beneath them. Agents may sometimes do so on our behalf, but without (necessarily) our knowledge. I wish it were otherwise!

Tito Gobbi, the great Italian dramatic baritone, wrote admiringly in his autobiography of “the ‘Comprimarios’ with a capital C, the king-sized ones who can split a demi-semi-quaver in two, true masters of rhythm and diction. They are precise in stage action, always well-dressed and faultlessly made up. They are the ones on which you lean in moments of uncertainty.” By the time the second or third cast of principals take their places, it is often the comprimarios or character singers that are the only link preserving the concept of the original production. My great friend and teacher Andrea Velis was such a performer who was brought into the Met by Faust Cleva to succeed the retiring Alessio de Paolis in 1961, At the time of his death in 1994 he had performed over fifty roles in over 1693 performances a the Met. Always dependable and impeccably prepared, he was loved by audiences and also by his colleagues. Many a time from my seat or from the wings I would see some of the most glamorous stars “lean” on him in moments of uncertainty. Whether audiences realize it or not, these are the performers who often give the production depth and a sense of reality. The photo that appears with the article is indeed Alessio de Paolis in the role of the Sergeant in the old Met’s Berman-Ritchard production of “The Barber of Seville.”