My first experience of Jon Vickers was as Siegmund in Die Walküre at the old Metropolitan Opera House on February 9, 1960. His earlier appearances as Canio and Florestan had been well received, but that night the theater came close to exploding. With Aase-Nordmo Lövberg as Sieglinde, he created a passionate, involved, intense Siegmund, equal in both lyricism, drama and voice to the live recordings of Lauritz Melchior. Reports vary about the number, but I remember seven solo curtain calls after Act I. They were not just curtain calls but screaming responses to his impassioned Wälsung. At intermission all one heard was the name Birgit Nilsson, because everyone was convinced that within a few days Vickers would join the great Swedish soprano in Tristan und Isolde. Sadly, it didn’t happen for fourteen years (because Vickers wanted really to be ready for Tristan), and then, at least at the Met, for only one performance, January 30, 1974. But that fantastic January night is as alive in my memory as though it were yesterday.

My first experience of Jon Vickers was as Siegmund in Die Walküre at the old Metropolitan Opera House on February 9, 1960. His earlier appearances as Canio and Florestan had been well received, but that night the theater came close to exploding. With Aase-Nordmo Lövberg as Sieglinde, he created a passionate, involved, intense Siegmund, equal in both lyricism, drama and voice to the live recordings of Lauritz Melchior. Reports vary about the number, but I remember seven solo curtain calls after Act I. They were not just curtain calls but screaming responses to his impassioned Wälsung. At intermission all one heard was the name Birgit Nilsson, because everyone was convinced that within a few days Vickers would join the great Swedish soprano in Tristan und Isolde. Sadly, it didn’t happen for fourteen years (because Vickers wanted really to be ready for Tristan), and then, at least at the Met, for only one performance, January 30, 1974. But that fantastic January night is as alive in my memory as though it were yesterday.

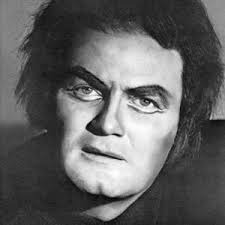

Vickers, the great Canadian heroic tenor, sang a large number of roles over the course of a more than quarter-century career. I enjoyed almost every one—a blazing Canio, a multi-faceted Florestan, the most thoughtful Otello conceivable, a slightly Hobbsian, overwhelmingly powerful and agonized Peter Grimes, a tortured Don Jose (not just the big dramatic stuff but a breathtakingly lyrical duet in Act I with Micaela), only once a memorable Erik in Der fliegende Holländer, a passionate and totally afflicted Samson, a crazed Ghermann in Pique Dame, a heroic, loving Aeneas and the most inspiring Parsifal I can remember. Vickers was such a vivid and individual artist that what he did burned his many interpretations into my memory. I only wish that I could have presented him after I became General Director of Seattle Opera, but it was too late.

What made him so great? He had a large, individual voice of as many colors as a rainbow, enormous power, dramatic intensity that made one feel that he was never acting but living a role (I have always wondered how anyone agreed to play Silvio in Pagliacci with Vickers as Canio because his rage and the knife stab always seemed so real that it was terrifying), a sublimely expressive piano or pianissimo when he needed it, and an unbeatable ability to convey literally a meaning of every word he sang. With him one could believe that he thoughtfully and logically came to the conclusion that Desdemona was having an affair with Cassio, that Jose could easily have been acquitted for temporary insanity, or that his brown-eyed Wälsung was really the hero he was meant to be.

Vickers was as memorable off stage as on. I had the opportunity to interview him quite a few times and to get to know him. He was mercurial. In the midst of a pleasant lunch he could explode if something was said with which he disagreed. He was also funny, very kind, loving with children. Deeply religious, he had violent opinions about pretty much everything. It really doesn’t matter what area one can mention; he was intense in all of them.

My last encounter with him took place in 1983, a few months before I became General Director of Seattle Opera. He came to Seattle to sing Peter Grimes; the Internal Revenue Service had ruled that he owed money; his managers had settled the suit, but the Service hadn’t received the word and notified Seattle Opera to garnish his performance fees. Vickers was beyond fury and said he wouldn’t sing. My predecessor, Glynn Ross, was out of town; I was in Seattle with no authority to do anything. Jon came to me and said, “I don’t know anyone else here, but I know you and I’m furious. You have to do something or I’m out of here.”—this said forte in his unforgettable voice with the edge that could cut through any orchestra ever assembled. I who had seen him like this before, said, “Jon, it’s a mistake. We will straighten it out.” I begged him for a few hours. He gave me two grudgingly. A few calls to Washington eliminated the problem. I called him and said, “Jon, the IRS acknowledges that you have paid. It’s all over.” He said, “OK, good. Goodbye.” Completely calm and happy. The mercury ran up and just as quickly down.

That is the best way I can describe his amazingly volatile personality, and there is not a General Manager or Intendant of that period who can’t tell similar stories. But it was all worth it. There never has been in my seventy years attending opera an artist who more completely lived out onstage what makes opera what it is. He has suffered with Alzheimer’s for a long time. I am deeply thankful that he is released. His memory will live on vividly to those of us who saw and heard him and to everyone else through those recordings that capture his individual, unforgettable art.

What a wonderful tribute to Vickers. Thank you for sharing such personal memories.