Recently I attended several plays in New York and London. The most thought provoking, creative and arresting was the Carmen Disruption at the Almeida Theater in London. Written by Simon Stephens after suggestions by the director Sebastian Nuebling and the mezzo-soprano Rinat Shaham (who, according to the program, had played Bizet’s heroine 400 times), the piece received its premiere at the Hamburg Schauspielhaus last year. Michael Longhurst staged the work at the Almeida, to a design by Lizzie Chachan.

Recently I attended several plays in New York and London. The most thought provoking, creative and arresting was the Carmen Disruption at the Almeida Theater in London. Written by Simon Stephens after suggestions by the director Sebastian Nuebling and the mezzo-soprano Rinat Shaham (who, according to the program, had played Bizet’s heroine 400 times), the piece received its premiere at the Hamburg Schauspielhaus last year. Michael Longhurst staged the work at the Almeida, to a design by Lizzie Chachan.

In London, mezzo Victoria Vizin took over the singer’s part. A bare stage with the body of a seemingly dead life-size bull in downstage center, the whole surrounded by black walls, provided the physical ambience of the piece. Two cellos placed upstage right provided the only musical accompaniment. Carmen is a thin, intense and very overly and audibly sexual young man (Jack Farthing), Jose a severe, rather restrained woman (Noma Dumezweni), Micaela a verbally loquacious blonde who cannot stop talking (Katie West), and Escamillo (John Light) a very macho, handsome man who alone created a character similar to his Bizet namesake. The music only touched on Bizet’s Carmen—some of the Habanera, a very, very effective use of part of the Card Song, a bit of Micaela’s aria and a very recognizable Toreador song. The cellos played throughout, basically contemporary music, all of which was very much background to the play. Bizet was cleverly interwoven into what the celli played.

A free take on the personalities of the familiar opera characters as they might be in today’s world, the piece was riveting. Farthing (Carmen) never sang but projected an intense 2015 sexuality in words and actions that threatened to make him explode. Dumezweni, the Don Jose, conveyed an aloof frigidity. She was intense but often still, while West as Micaela played an irrepressible, hysterical older teenager who couldn’t be quiet. John Light, the most dressed up of the four, made a handsome, extraordinarily athletic Escamillo. The solo Chorus, Vizin, who does quite a bit of singing, had a costume that suggested the operatic gypsy, whereas the Singer (Sharon Small), who rarely sang, played a very uptight, attractively and somewhat stylishly dressed but very confused person from a different milieu.

The solo Chorus, Vizin, who does quite a bit of singing, had a costume that suggested the operatic gypsy, whereas the Singer (Sharon Small), who rarely sang, played a very uptight, attractively and somewhat stylishly dressed but very confused person from a different milieu.

The references to Bizet appeared during the 90-minute production at roughly where one would hear them in the Bizet opera, and related in a weird way to what was going on. Micaela’s “aria”, for instance, brimmed over with teenage terror. Making the story contemporary and at the same time surrealistic and only vaguely comprehensible created an event that proved totally fascinating. These characters existed in Carmen’s milieu in 2015.

Trying to describe the action is beyond me. A lot of unusual things happened, including the bull’s momentary vivification toward the end with his blood’s staining the Singer’s costume. One was caught up in each character’s personality when he or she was speaking. Sometimes they related to each other; often not. The reason Escamillo seemed the most familiar came from his truly amazing physical feats (climbing all over the back wall and striking seeming impossible physical poses), and his desire for Carmen even if he didn’t seem the type to pursue a male. That the Micaela annoyed me might have been intended or just the way I reacted to her. Every character offered a very different kind of person, and I’m sure every member of the audience found his or her own reading of each.

If all sounds confusing, it was, but it was also totally gripping, great theater, requiring and receiving complete concentration from the audience and intense dedication by the actors, all of whom gave brilliant performances. The play is running until May 23; the more times you have attended Bizet’s opera, the more fascinating Carmen Disruption will seem.

In most cases the lack of a narrative has become more and more a reality in Anglo-American theater, and I have to say that I usually don’t like it. I am not asking for a return to the well-made play, but unless the writing direction and acting is as brilliant as Carmen Disruption, the result becomes annoying.

I caught Airline Highway in one of its last Broadway previews. At first there again seemed to be little or no story line, but as the drama progressed the characterizations and the actions of all the characters captured the milieu of New Orleans today better than any piece since the great works of Tennessee Williams. A production from Chicago’s (to me) consistently interesting theater, Steppenwolf, written by Lisa D’Amour was directed by Joe Mantello whose cast included a tired Madam, a prostitute, a sexy ladies’ man who had left New Orleans and now returns with a young woman who is trying to interview everyone, plus drunks, dope takers, and a very strong willed and outspoken gay man. It’s the kind of play that didn’t come together until near the end, but when it did was more than rewarding.

I caught Airline Highway in one of its last Broadway previews. At first there again seemed to be little or no story line, but as the drama progressed the characterizations and the actions of all the characters captured the milieu of New Orleans today better than any piece since the great works of Tennessee Williams. A production from Chicago’s (to me) consistently interesting theater, Steppenwolf, written by Lisa D’Amour was directed by Joe Mantello whose cast included a tired Madam, a prostitute, a sexy ladies’ man who had left New Orleans and now returns with a young woman who is trying to interview everyone, plus drunks, dope takers, and a very strong willed and outspoken gay man. It’s the kind of play that didn’t come together until near the end, but when it did was more than rewarding.

Two other plays disappointed. A one-man show in New York labelled Churchill recycled all of his most famous quotes. The actor, Ronald Keaton, sounded a little like Churchill, but brought no unfamiliar material to his performance. An evening in London called Buyer and Cellar, a stint by a comic describing what it was like to work for Barbra Streisand had its moments. Funny for a few minutes, Michael Urie’s characterization of the actress and his reaction to her lasted for almost two hours, much too long and too repetitive. In all fairness, the sold-out crowd never stopped laughing uproariously at whatever he did.

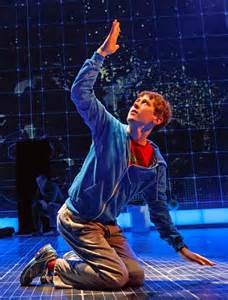

One totally gripping theatrical experience came from The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Because of my plane flight to London, I could only see Act One, but this was great theater, brilliantly acted, the story of the problems of a severely autistic young man. Alex Sharp, a young actor in his Broadway debut, created the character with shattering realism. Still apparently a teenager, he could convey the much younger boy’s personality, its changes, his problems and his wildness with astonishing, frightening reality. Francesca Faridany, the social worker asking him questions, explaining to the audience, dialoguing with the boy had just the right attitude and actions. Everyone in the cast was good as was the simple, largely empty stage that focused everything on the boy’s problems. The direction by Marianne Elliott gripped me for the start, and the largely empty set by Bunny Christie focused all attention on boy and his state.

Alex Sharp, a young actor in his Broadway debut, created the character with shattering realism. Still apparently a teenager, he could convey the much younger boy’s personality, its changes, his problems and his wildness with astonishing, frightening reality. Francesca Faridany, the social worker asking him questions, explaining to the audience, dialoguing with the boy had just the right attitude and actions. Everyone in the cast was good as was the simple, largely empty stage that focused everything on the boy’s problems. The direction by Marianne Elliott gripped me for the start, and the largely empty set by Bunny Christie focused all attention on boy and his state.

The Nether, a play that sold out its entire twelve-week run at the Duke of York Theater in the West End, created a happening in virtual reality that left me totally cold. A young girl apparently was abused and eventually killed but the onstage happening and what was going on in the conversations of never more than two people at one desk made little sense to me. At one point the back wall rose to show quite an expansive forest. I basically didn’t get it at all.

The Nether, a play that sold out its entire twelve-week run at the Duke of York Theater in the West End, created a happening in virtual reality that left me totally cold. A young girl apparently was abused and eventually killed but the onstage happening and what was going on in the conversations of never more than two people at one desk made little sense to me. At one point the back wall rose to show quite an expansive forest. I basically didn’t get it at all.

Leave a Reply