(*Corrections to paragraph begun with *below. plus added bit of Denby poem at the end)

You’d think ballet would be good at expressing the exhilaration of love, and it is, but only if it can cap it off with betrayal, tragedy, death! Consider Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, La Sylphide, Giselle, Scheherazade, La Bayadere–not to mention the moderns, Balanchine and Tudor in particular. (Ashton is more cheerful.) Maybe choreographers think it would be just too easy–too cheesy–to exult in love in dance, the native tongue of emotional exultation.

But we do have the Nutcracker, where a sweet girl not only gets to have her prince but eat a world of candy too. (I mean, it couldn’t be that she gazes upon mouthwatering delectables–dancing sugar plums, marzipan, Arabian chocolate, candy angels–for an hour and then doesn’t get to enjoy any of them, eventually, when no one’s looking, could it?)

The best love dance I know is Mark Morris’s for Drosselmeier’s nephew and Marie (aka Clara) in The Hard Nut, his version of the Nutcracker, and I don’t think it’s an accident that this is a modern dance. Marie does the plainest steps over and over, as if she’s trying to acclimate herself to this new amazing feeling, periodically lunging and flopping forward as if her infatuation had turned her body to jelly. The duet ends with her running up to the lad and kissing him, then running away so she can do it again–and again. It’s so sweet and funny–the giddiness so recognizable and that they kiss on every high note, as if romance always moved to the beat because it is inscribed on our hearts, whether or not we’ve experienced it in the world before. (There’s a Hard Nut video, but it doesn’t approach the live experience. I have that on others’ authority, too. Here, though is one scene, with the unisex snowflakes wearing icecream swirls for headdresses, which gives you some idea of the spirit of the dance.

.)

*[Musical references corrected.] To celebrate Valentine’s Day I’m guessing, the New York City Ballet gave us Peter Martins’s streamlined but otherwise full-length Swan Lake last week and now moves on to one of its inspirations: Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 (known for decades as Ballet Imperial, as it is still known in certain quarters). Balanchine heard the tragedy of Swan Lake in various Tchaikovsky works: in the “Diamonds” music, from Symphony No. 3, for Jewels (which ends the NYCB winter season, next week), and in Tchaikovsky’s Suite No. 3, from which Balanchine created a ballet of the same name. But I’m most eager to see his ballet to the piano concerto because the terribly sad ending of Martins’s Swan Lake alludes to the terribly sad middle of this Balanchine, where the–I was about to type mother, and there is something maternal about her–ballerina bends down to hug the lonely danseur before departing through a narrow gauntlet of women. I can’t remember whether in the Balanchine she bourrees backwards as she does in the Martins–keeping her eyes as long as possible on him. I think not, but we’ll see.

I strongly recommend the lovelorn All-Balanchine program this week: besides Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2, the equally emotionally illuminating–and trying–Liebeslieder Walzer.

Here is a chunk of my Friday review for the Financial Times on Martins’s Swan Lake:

New York City Ballet is distinguished not simply by brief and plotless dances, but by how transparent they make the operations of art. Illuminating and intensifying experience, the ballets – by Balanchine in particular – are like magic tricks that are all magic and no trick.

This season, however, Peter Martins’ renditions of iconic story ballets dominate. The balletmaster- in-chief strips story of connective tissue and thus sense. Balanchine kaleidoscoped a story’s layers into metaphor – poetry; Martins simply adds or subtracts elements.

Swan Lake, the season’s final story offering before we return to plotless Balanchine and Robbins, brings home the difference, because Martins has built his four-act ballet around Balanchine’s sublime two-act version. Rather than making him look worse, however, the proximity to genius makes Martins choreograph better. Swan Lake is his best story ballet.

Martins has good instincts but bad follow-through. His addition of a jester to the court scenes, for example, has promise: wherever protocol and hierarchy rule, there is room for a “licens’d Fool” to turn things on their heads. But this jester doesn’t even mess with the steps. And what Martins gains by enhancing the lustiness of the national dances that preface evil Odile’s seduction of the prince, he loses when he throws in a chaste shepherdess number and a plucky pas de quatre that seems to have flown in from fairyland.

In the Balanchine-indebted lakeside scenes, on the other hand, the steps mean many things at once, each of which deepens the drama. The swan corps shift places like a flock on the wing but also like waves on the eponymous lake of tears. As animals, these creatures live what they feel. In the Swan Queen’s final moments with Prince Siegfried, they curl up…

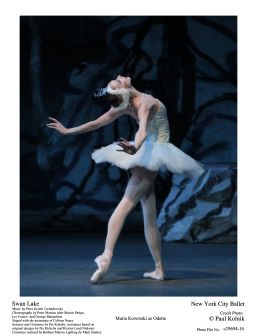

Isn’t she lovely? Maria Kowroski, swan.

Photo by Paul Kolnik for the New York City Ballet.

For the whole review, click here.

I am in the minority–among ballet aficionados and critics, too, I think (though I haven’t read all of the reviews)–in preferring Martins’s Swan Lake to his Sleeping Beauty, which played earlier this season. This isn’t to say there aren’t big problems with the Swan Lake, only that it seems less dully docile, and has sublimity and tragedy where you need it: in the promise-making and parting scenes by the lake. That is, whatever problems with coherence this Swan Lake has, The Sleeping Beauty‘s are more egregious.

As is often the case when one is alone in an opinion, this general preference depresses me, because it suggests that those who are really devoted to ballet care less about the integrity of a work than that it hit various high notes and/or give their favorite dancers longer in the spotlight.

I could understand their point of view if we weren’t talking the house of Balanchine, whose mission was to have the choreography be the star, which doesn’t mean the dancers don’t matter but only that they don’t matter more than the dance; Martins’s Sleeping Beauty doesn’t allow the dance to matter much. So who cares that it includes all the iconic moments like some greatest hits album–the Rose Adagio, the variations of the fairies, the Vision Scene?

Many viewers and critics who have admired this or that dancer in Martins’s production were appalled by ABT’s Sleeping Beauty a few years ago, about which I have gone on and on. (I’ve also gone on about the Martins version already) And, sure, ABT’s may have been a fiasco, but it was a mainly intelligent and brave fiasco–in which the choreographers largely understood the story and the characters (minus the storybook final act, which they so truncated as to make it hardly read), even if they hadn’t entirely figured out how to turn it into good dancing and good theater. For example, they understood that the story depends on some suspense.

This is how friend and Foot contributor Paul Parish put it to me in an email recently when I was complaining that the Martins production was making me forget why The Sleeping Beauty has been such a big deal for a century.

Paul starts with the final wedding pas de deux in which the Prince rotates Aurora back and forth in attitude (the crook-legged position) so we can see her from all angles.

That attitude based on a little figurine of Mercury you can hold in your hand and rotate— the statue itself is famous for how it continues to “compose” as you rotate it; there are three major faces and it is lovely in all the intervening ones — has this way of reminding you of the larger mysteries of the blind side: what’s going on that you’re not thinking of, what’s going on that you can’t see, who’s brooding resentfully that you’ve forgotten about altogether [for example, the evil Fairy Carabosse, left off the guest list for Aurora’s christening party] and the way that at the peak of your bliss the enemy can be waiting to attack. The music is full of alarms — all through, the most luxurious variation-music for the fairies has sudden outbursts of trumpets. But you should not get paranoid.

The ballet is really about faith and compassion. Many people say that there’s no suspense: We know the outcome, she’s not going to die. Well, they tell you things like this all the time: This operation is a piece of cake, you’ll just go to sleep at 11 AM and you’ll wake up at 1 with a knee that works again (or you name the procedure). Fact is, we don’t know; the suspense is still there.

Isn’t that a great explanation? Thank you, Paul!

So timing matters: you don’t have suspense without the suspension of action. In Martins’s Sleeping Beauty, one fairy is just completing her variation when the next barges in and waits in starting position for her turn. It’s very distracting and makes you feel that the first should hurry up and finish. Couldn’t we dwell for just a moment on each fairy’s unique gift? After all, it’s the combination of them that make Aurora beautiful straight through to her soul. And it makes the arrival of Carabosse the evil fairy more alarming.

And when Martins reduces the time for the hunting outing and the scary forest journey where Prince Desire hacks his way through the tangled Carabossian brush to get to Aurora’s castle, the effect is to turn our hero into a spoiled brat. The prince gets whatever he wants as soon as he wants it. He doesn’t feel like hanging out with his fellow aristocrats because he’s in a lousy mood? Fine, they’ll pack up their picnic baskets moments after they’ve settled down. He wants a princess to love? Not to worry, Lilac Fairy will deliver her so fast that we hardly register the kiss that brings her back to life after 100 years of slumber.

Why should I rejoice at their marriage when he’s such a pig–and she’s not so interesting either, as the gifts the fairies bestowed on her (serenity, courage, pluck, etc.) are a blur?

But critics and ballet forum posters didn’t seem to mind any of this, engaging in the usual archaic ballet talk–about what each dancer brought to the pas. This is why it’s refreshing to go to the ballet with people interested in other things. They immediately pick up on the holes in the story. I once took a friend to ABT’s Swan Lake. After the first act, he said, Wait, that’s the prince? The guy sitting in the corner? How are we supposed to care about him if he’s sitting there the whole time? Exactly.

I think people worry that they’d be giving up the “classiness” of ballet if they admitted that coherence mattered. I think they should admit it matters.

PS. Apropos of ballet fans in odd places, I just got this email from my friend Andy Podell, a fantastic playwright. (He was in the Samuel French Off-Off-Broadway Short Play Festival this summer and blew the competition out of the water. I had begun to feel that the assignment, to put on such a short play, was impossible, and then his “Mom Was a Carney”–about a lovely lost soul hungry for donuts–came on and in a delicate and pillowy way dug to the heart of mother-loss sadness. In 20 minutes. Amazing. Anyway…. Andy writes):

Went to Jim Carroll’s memorial next door at St. Mark’s Church and it turns out that Carroll, oddly enough for a punk neo-Beat heroin addict, was a big ballet fan and was friends with and admired Edwin Denby. Ever read any of his dance criticism?

Yep, sure have. Besides being a dance critic–preeminent–he was also a poet, and had this to say about our beloved underground:

The subway flatters like the dope habit,

For a nickel extending peculiar space:

You dive from the street, holing like a rabbit,

Roar up a sewer with a millionaire’s face.

To hear Denby himself read the whole of “The Subway” shortly before his death, at age 80, in 1983, click here.

Leave a Reply