I met Julia Kurtyka in winter.

She had worked to invite me to guest conduct an orchestra that she was involved with, the Birmingham Bloomfield Symphony Orchestra, just outside of Detroit, in a special concert that would feature her protégé, violinist Caroline Goulding, in a performance of Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5.

Julia had been the concertmaster of the Adrian Symphony Orchestra long before I became its music director. Since then she had moved on to other projects, but we shared mutual friends and that led to the invitation to guest conduct the orchestra she was deeply involved in.

When I finally met Julia she was suffering from cancer, but you would have never known it. She was feisty, strong, opinionated and still full of life. She was quick to smile, held people accountable for their actions, honest in her assessment of others, unusually gracious. Tough, soft: opposites you could respect.

A few months after that concert, Julia was honored by the BBSO for her many years of dedicated service. By then, she was in a wheelchair, but when we spoke together at intermission, she retained that radiant sense of joy that I had already come to treasure. Clearly her health was failing, and, as I left the hall, I already sensed that it would be the last time I would see her.

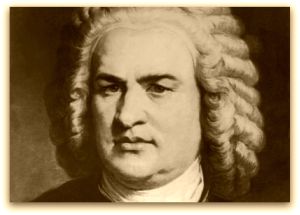

So, when I was asked to speak at this year’s Lexington Bach Festival north of Detroit, Michigan, I knew I would accept because I knew that this project was Julia’s “other love”. A dozen years old, the festival brings together some of the region’s very finest musicians to perform all kinds of music, always including a connection to Johann Sebastian Bach. Lexington is a small town that looks out on Lake Huron, and the intimacy of the church locales renders a kind of familiarity that is truly rare among such festivals. People know each other in Lexington.

They knew Julia. They remembered her, and they felt a sense of loss.

The 2011 Lexington Bach Festival felt like a joyous funeral, an elegy with surprisingly few tears. Julia was nowhere to be found, but her spirit pervaded every moment. She was every second sentence.

Her brother was there, and as we chatted together our voices would quiver with a sense of loss, or rise up in strength as we talked about this extraordinary woman and the life she had led as a teacher, performer, administrator, and friend.

During one of the festival’s programs, there was a beautiful, quite poignant work performed. It was written by a very fine musician, a conductor/bass player/composer named Clark Suttle Over a meal before the concert, he displayed a wry sense of humor, telling me that Julia was a very forgiving person. “I was once 45 seconds late to a rehearsal,” he told me. “Three years later she forgave me.”

Clark’s memorial to Julia was a composition called The Last Kiss, a reference to a practice in Julia’s spiritual tradition in which the mourners kiss the forehead of the deceased as they pay their final respects.

Julia’s brother gave her The Last Kiss.

As I drove away from Lexington after the last notes had faded away, I thought about what remains of our lives after we are gone. Is it the protégé we nurtured? The memory of the music we made? The friendships we formed? The family members we helped along the way?

Or is it the mantle that others choose to take up?

One of the highest compliments to any endeavor, large or small, is that it can outlive those who helped form it. Without Julia’s presence this year, others had to step in to fill the void. It was hard work, and I imagine that several times they must have wondered how it was that Julia had been able to get everything done while making it all look so easy.

You may have never heard of Julia Kurtyka, but I wish you had known her. And even if you don’t know of this particular series of concerts in a small town in Michigan, you can take it from me that the Lexington Bach Festival is still making beautiful music.

And that is a testament to all of those people like Julia who labor behind the scenes. It makes you realize that every institution we revere probably began as a conversation across a cup of coffee, and that perhaps the ones who sat there dreaming have already been long forgotten.

Many of them who may have worked the hardest never once took a bow.

Leave a Reply