Part 6 of 6

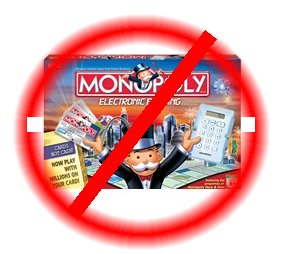

The monopoly of the past century was finished.

All seemed lost.

All seemed lost.

That year was a catastrophe.

As the months progressed, income plummeted for the organizations while the expenses continued at the same level as before. Again this was because the organizations tried to honor the promises they had made months earlier when they had announced their concerts, repertoire, and guests.

Finally, when the season ended they made drastic cuts.

Everyone hoped people would return to the concerts, but many didn’t.

They also hoped their donors would give again, but many were scared of losing their jobs, so they didn’t either.

The revenues were so low that, even with their recent budget cuts, the organizations continued to accumulate deficits.

Suddenly the gap was too wide for the organizations to stay in business without truly drastic measures.

Because of the implications of the next apocalyptic action, it was delayed until it was obvious that this final, most onerous step was necessary.

They spent the endowments.

Because there was no income to keep the organizations running, their endowments were raided in order to meet the expenses associated with their current obligations.

It is important to remember that, at the point the endowments were being withdrawn from their protected status, the financial markets were depressed. This meant that not only was the interest being earned from the principal already under projected budget levels, the actual principal was also depressed in value.

The cost of spending down the endowments was, therefore, much higher than the value of actual income generated, when measured against traditional valuations.

This was the worst of all possible worlds: spending long-term investments at discounted valuations for short-term needs.

Many savvy people worried that they would never see those endowments again funded at pre-crisis levels, but they had no choice. There was simply no other resource to use.

In effect, they spent their future to pay for their present. It was the only remaining way to stay in business.

Again, there is no need to assign blame. Looking back now, it is clear that there were no other viable options: The choice was to die immediately, or to live long enough to fight for the future. Anyone would have made the same choice.

The concerts during that time were particularly poignant, but the orchestras played for empty seats, and the donors didn’t have the resources to reverse the situation.

The writing was on the wall.

It was clear that all the predictions, all the precedents, and all the knowledge everyone had was entirely inadequate to the situation.

It took some time for the scenario to play itself out. During the next several years there was a tremendous upheaval in the field.

Many of the organizations failed during that period. They are remembered now with much veneration, since they made great art. Their recordings and much anecdotal evidence attest to that fact.

This decade effectively marked the end of the old model.

Things looked so bleak that few noticed, amid the ashes, that a new phoenix was arising.

Of course, as we know now, there was not just one phoenix rising, but many.

It was not the art that was flawed, and, thankfully, the art did not die alongside the business model.

Next: a postscript

Leave a Reply