They were in great danger, but they could not see it.

Of course, in the background were frequent economic expansions followed by recessions. The recessions were particularly tough on the organizations because their business model didn’t allow them to react quickly enough.

When the audiences and contributions would get smaller as a result of the temporary economic downturn, there would naturally be a deficit.

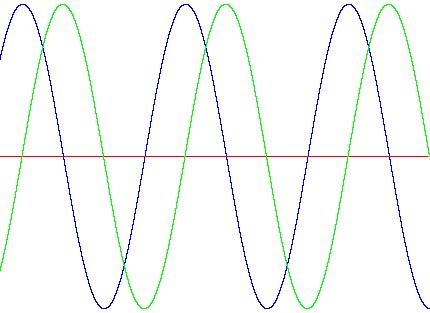

It was as if there were two slopes, similar in shape but one always a bit behind the other. The forward slope represented revenues, while the following slope represented expenses.

During economic downturns the organizations’ revenue slopes would plummet, although the expense slopes would always lag behind the revenue in dropping too.

During economic downturns the organizations’ revenue slopes would plummet, although the expense slopes would always lag behind the revenue in dropping too.

This occurred because the organizations wanted to keep their word about the repertoire and artists they had announced. They had already committed themselves and they didn’t want to lose their audiences.

If the recessions were lengthy, major cuts would be scheduled for the following season or even delayed and negotiated during the next round of contracts – sometimes several years later. This time lag in response to the downturns was critical in accumulating deficits.

Conversely, during times of expanding resources the organizations became optimistic so they looked for new ways to serve their community, enlarging their offerings. The new programs were then formalized and came to be expected each year. Naturally, the musicians were paid for the new offerings. This helped the musicians because they could count on predicable income at a higher level.

During the expansions the revenues would gradually rise again, but it was not common for the expansions to either last long enough to fully pay off the debts, or for the organizations to discipline themselves from growing their expenses.

When there would be another recession the newly-expanded offerings again worked against the organizations. Since they were in multi-year contracts with little flexibility, the situation kept them from responding quickly to the economic meltdowns by quickly cutting programs and reining in costs, as any other business would have done.

It is important to realize that assigning blame is useless here. The organizations wanted to serve the communities and to make great art. The musicians wanted to do the same and to make a living doing so. These were natural motivations.

To make matters worse, during the recessions the government would cut back on its arts support. Over a number of years, that support dwindled considerably and, in some cases, completely stopped. By the time of the eventual crisis, as a predictable resource for maintaining economic stability in the arts sector the government’s support had become irrelevant. It was simply too small to be a meaningful factor, except as one more missing element in the economic vacuum.

However, as long as the economic downs and the ups were in relative moderation, this model held up. This is because, although the model was flawed, it was run quite well.

Artistically the orchestras were so remarkable they could produce a remarkable result in very few rehearsals, and the managements did an incredible job of finding new sources of earned income and soliciting business and philanthropic support. Many audience members remained loyal, and there was a constant inflow of new audience members trying out the product. If they had returned consistently and in sufficient numbers perhaps things would have turned out differently. Just before the crisis many of the organizations focused on audience retention rates. Although they were late in noticing how important it was, we should note that they DID realize they had a problem and had begun to address it.

It is hard to believe, but although there were times of upheaval there were also periods of relative calm. It wasn’t a perfect world, but it seemed to work, although everyone always seemed to talk about how difficult it was to feel secure about the future.

Then the bottom fell out.

Leave a Reply