In my last entry I wrote the following:

In my last entry I wrote the following:

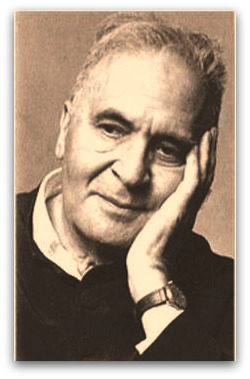

I want to start this series of blogs on personal artistic development and its relationship to building communities. Naturally, there are many interpretations of the word “community” – ranging from shared geography to any group with a shared interest. Recently, I have been thinking of the community which formed around Bruckner’s music – and of one conductor’s role in helping establish and foster it over a very long lifetime: Bruno Walter. I’ve come to understand more clearly what his personal journey entailed. As an interpretive artist Walter grew in understanding Bruckner’s music over a lifetime of study, and his own growth helped foster the community that would be formed around the composer.

Today I want to continue exploring the subject

Many hours of score preparation are done in silence.

You sit and stare at a page, imagining the sounds as you look at the notes, articulations, dynamics, tempo indications and all the other myriad details which attempt to indicate the moment-by-moment intricacies and actions of live music-making. To someone looking at you while you are studying, there is nothing to see. You appear as if you are resting, but your mind is active, and your inner ear is working as hard as it can to create a landscape of music that you’ll try to help come alive in rehearsal and then later, in concert. As you return to the score, day after day, you not only learn the music, but you begin to get new perspectives on the work as a whole. Sometimes yesterday’s question becomes today’s answer; sometimes you rethink a tempo or the dimensions of a ritardando, or how loud this forte will be compared to THAT forte.

For some musicians, the score is the only source they want to interact with. I know conductors who actively DON’T listen to other musicians’ performances of a work they are studying because they don’t want to be influenced, even unconsciously, by someone else’s ideas. I respect that viewpoint – in that they are trying to express the composer’s ideas, rather than a warmed-over version of Conductor A’s interpretation of them. The last thing you want to do as a re-creative artist is to create a Frankenstein-like interpretation, borrowing one moment from this interpretation and the next moment from that one – as if merging different views of a work together would make a satisfying whole.

For myself, after I’ve done enough work on my own, I love to listen to others’ views of the work I’m working on. I confess that sometimes they point out a detail I’ve missed, but more often, it is a way of “having coffee” with another conductor. You listen to how they approach a problem. You get to see if their answer “works” and you REALLY see their feet of clay when it doesn’t. Those moments are cautionary, because a master conductor’s failings are telling. You look at the score and think, “If THIS conductor can’t solve that problem, how am I supposed to???” And sometimes you hear a performance that, while successful, doesn’t represents a vision of the work that matches your own. Those can be fascinating experiences too. You say to yourself something like, “I would never conduct it that way, but it is totally convincing!”

Right now I’m preparing a Bruckner symphony. I’ve spent much of the summer in silence with it, and now I’m listening to a number of recordings – “having coffee” with the likes of Jochum, Haitink, Sawallisch, Klemperer, Tennstedt, Masur, Kubelik, Karajan, Abbado, Bohm, Celibidache, Chailly, Barenboim and others.

One morning not long ago, I spent 40 minutes on the first movement of Bruckner ‘s Fourth – “having coffee” with Bruno Walter. Actually, I spent that morning with TWO Bruno Walters.

The experience was revelatory, and it got me thinking about the subject of this series of blogs.

The first Bruno Walter was a middle-aged man. He was guest conducting in 1940 with the newly-created NBC Orchestra, and the orchestra created for Toscannini showed itself to be a truly virtuoso instrument. One of the interesting things about the NBC is that it was made up of extraordinary musicians, but each of the early broadcasts marked the first time THAT particular orchestra had played the work. Because of that fact you get a musical mix of seasoned musicianship and freshness. Walter’s recording of the Bruckner Fourth (on the Pearl label) is from a live radio broadcast, and I gathered from reading the CD booklet that the acetate from the radio broadcast, complete with audio pops and a rather “closed” sound from the infamous Studio 8H, formed the basis for the recording. You don’t buy this recording for the quality of the sound, but as a way of peering into a moment in time.

The second Bruno Walter I spent the morning with was an older man. In that recording (on Columbia Records) he conducts the Columbia Symphony Orchestra in the early 1960’s. The tempos are slower in this recording. Each movement is longer than the earlier performance, but there is more at play here than just speed. The later recording is grand. It holds together as a single unit. It isn’t simply the much improved quality of sound, it is the musicianship we experience. The phrases breathe, the a tempos seem natural, and the shape of the dramatic arch seems completely “right”. You don’t get jostled around listening to this reading. It has majesty to it and a kind of serenity that seems to match the world of the composer, the music itself and its interpreter like a hand in glove. It simply fits.

Like the NBC in the 1940’s the Columbia Symphony Orchestra was not an ensemble with a long history. Instead it represented some of the very best studio musicians in the business. Walter made a number of recordings late in his life with this group, and there are even recordings of studio rehearsals. Listening to those sessions shows him to be a gentleman on the podium at the same time that he demands a very clear musical result from his colleagues. His manner of addressing the musicians as “my friends” or even courteously by name was the model of respect from a musician whose storied history and enormous cultural background could have led a lesser man to a very different approach in dealing with his musical colleagues. It isn’t hard to love Bruno Walter, and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra’s recordings reveal him to be a musician in the center of good taste. The tempos are not surprising, nor are the climaxes overblown. The whole CSO series is consistently satisfying, and you would expect to look to others to surprise you with extremes of interpretations.

Or you could look to his 1940 recording of Bruckner’s Fourth with the NBC Symphony.

I’ll explore the surprises I found there in the next entry.

Mr. Dodson,

Enjoyed very much the insight into a conductor’s work.

Best wishes for your weblog.

While the CSO recordings are wonderful documents, it is easy to over-romanticize their connection to the musical otherworld. I studied with a horn player who played the sessions with Walter and Stravinsky, and he had a great story about the Firebird recording with old Igor. My teacher was playing 1st horn in the recording session, and when the Bercuse wound down and the glorious Finale began, Stravinsky just stood there with his eyes closed and arms outstretched! The hornist held the first note as long as he dared before realizing that Stravinsky would not give him any kind of beat. When he moved from the F# to the E, he had already established a slower tempo and had to stick with it. One take (that’s what the studio guys get paid for), one lousy conductor, and we have the “definative” interpretation directly from the composer!

Mr Dodson,

Thank you for this important article. I will foward to friends.

Thank you again,

Martha

That is a valid point about Stravinsky, but there is also an enormous valley between the abilities of Walter and Stravinsky on the podium. It is generally agreed that the latter was as often as not a terrible conductor, even of his own work, whereas I don’t know of anyone who discounts the talent and technique of Walter (especially by the time of the Columbia recordings).

I was that horn player mentioned. It’s a very true recollection of that moment. But, those were great moments that I cherish in my old age, that I was a part of this history.

I am trying to remember the Mozart symphony Bruno Walter conducted during these sessions. They are my happiest memories of being a musician. The producer asked him to take a minute from the recording as it would not fit on the LP as it was recorded. I couldn’t imagine taking a minute off of such a beautiful interpretation. He did and I can’t imagine wht happened to that minute, that take was just as beautiful as the first take.

What a meaningful post. I first learned to love classical music conducted by Bruno Walter. A wonderful, cigar smoking Jewish guy by the name of Max Schwartz started me on a life long journey by telling me about Bruno Walter. What followed was a collection built around his recordings. Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler, and especially Mozart. I eventually earned a MM from Juilliard and am now a chef instructor in a college, but have never lost my gorunding in his amazing recordings.

Throughout my life I always came back to his performances and am doing so again as I get older. Cramming for finals? There is a verity and spirituality in so much of what he recorded. The scope, understanding and all encompassing humanity that comes through have guided me through my life, in good times and bad.

And for Mr. James Decker, if you read this, please contact me. I have been looking for someone who actually worked with Maestro Walter.

Thank you for everything.

All the best.