Andy Warhol considered himself a camera. He was more like a mirror. Into his mirror the culture gazed. Every little thing about the people in it – from the soup in their bowl to the money in their pocket – is art.

In my youth when visiting friends, a photo of the host on the wall was worrying but not conclusive, especially if some other person, place or thing shared the frame and could be considered the point: a favorite haunt, horse, child, lover, dead parent. Two or more photos of the host alone? No need to ask which way that wind blew – into a full-blown case of narcissistic personality disorder. I might wrap that person up but never take him home.

Today guileless youth post hundreds of photos of themselves on Facebook. They carry themselves in their phones and on their laptops, never far away from the chance to take more photos of the subject dearest to their hearts, as if they were each their own church, genuflecting at their own altar.

Someone peripherally involved with a struggling chamber orchestra recently confided that the problem is the music director. He tries to sell the idea that art is worth an encounter rather than the reassurance that the community already owns the art and has a home there.

Again and I know I’m being an old fart: For me the appeal of art was that it offered something greater than myself, and that by engaging it, I could find my way into the deep end of the pool.

Enter Warhol, whom I long resisted. I used to think he made the idea of the deep end obsolete, and I mourned its passing. In time I realized that he made the idea of the shallow end obsolete, that everything can open up and contain a world.

Now at the Seattle Art Museum, Love Fear Pleasure Lust Pain Glamour Death: Andy Warhol Media Works is Warhol at his most unguarded. He loved the people represented here, and they loved him. For him, they dispensed with the shellacked smiles of the camera ready, caught the mood of their moment and reflected it back to him.

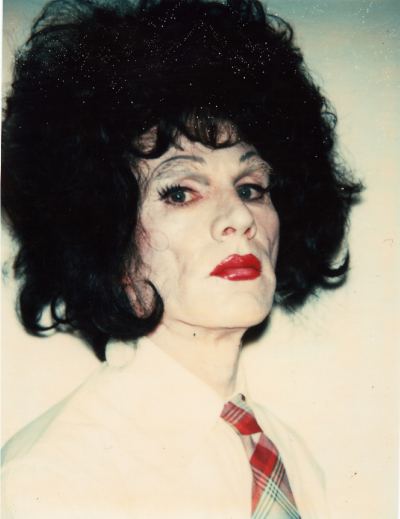

Himself he didn’t spare. Why is it that Warhol’s version of himself as an old drag queen has a Wife-of-Bath elan while Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits as aging matrons are dry at their root? Adrian Searle wrote of the series that Sherman’s work is “more durable than it looks.” Searle is brilliant, but what does that mean in the context of now? Like Oscar Wilde before him, Warhol taught us to judge by looks.

Curated by Marisa Sánchez, Love Fear Pleasure Lust Pain Glamour Death is a clean, straight shot of Warhol, including his Screen Tests projected large across two galleries, photobooth strips, sewn photos and Polaroids. The man who had a lot to say about being alone was almost never alone. These are his people, his team pre, during and post Factory. On the evidence of this show, despite being shot, being the subject of endless bad reviews and in possession of many personal foibles, it was great to be him.

Curated by Marisa Sánchez, Love Fear Pleasure Lust Pain Glamour Death is a clean, straight shot of Warhol, including his Screen Tests projected large across two galleries, photobooth strips, sewn photos and Polaroids. The man who had a lot to say about being alone was almost never alone. These are his people, his team pre, during and post Factory. On the evidence of this show, despite being shot, being the subject of endless bad reviews and in possession of many personal foibles, it was great to be him.

Only one quibble: the title. Why Love Fear Pleasure Lust Pain Glamour Death? Isn’t that title taken already? I refer of course to Bruce Nauman’s 1983 neon circle: Life, Death, Love, Hate, Pleasure, Pain.

Leave a Reply