Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed

citizens can

change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

Margaret Mead

When I met Chris

Jordan, he was a Seattle lawyer representing a now-defunct pipe line company. Its product had

ruptured on June 11, 1999, allowing 236,000 gallons of gasoline to pour

into the Whatcom and Hannah creeks near Bellingham, turning them into fireballs. Two

10-year-old boys playing by the riverside were killed. Jordan’s job was

not to help anybody deny guilt. That trial was over. His more limited goal was to keep his clients out of jail. He did not succeed.

Some lawyers are able to recover from a case like that, and some have

nothing to recover from. They are, after all, just doing their jobs.

Haunted by the deaths and the river on fire through human negligence, however, Jordan didn’t give up his cushy corporate job and switch to the other side. He withdrew completely, never to practice law again.

But while he was still on the

case, he cold called me to introduce himself as a lawyer, not an artist. When he

couldn’t sleep, he said he liked to take a 4-by-5 camera on the streets

of his Belltown neighborhood late at night to photograph the trees. I don’t ordinarily do studio visits with lawyers who happen to pick up a

camera. But there was something compelling about him, even over the

phone.

Here’s part of the story I

wrote in 2001, the first in what is now a long and international list.

With no flashes or other lighting equipment, Jordan uses long exposures

to take advantage of the light that’s there: traffic signals, street

lamps and neon signs.

Granted, city trees have tough lives. That’s what interested Jordan in

the first place, their circumstances and secret beauty.This is their secret: Stranded in urban jungles, they are still able to shine. Neon light gives them a

gorgeous glow. In his photos, royal blues and jittery yellows, magentas and

silver-gold bathe long trunks, clustered leaves and twisted

branches in an artificial radiance.

“Planted in straitjackets of nutrient-poor, compacted soil, surrounded

by asphalt and haphazardly pruned to protect buildings and phone lines,

they struggle to live,” said Jordan, 37.

“Yet at night,” he continued, “the colored glow bathes them in wild

colors. They could be modern dancers on stage.”

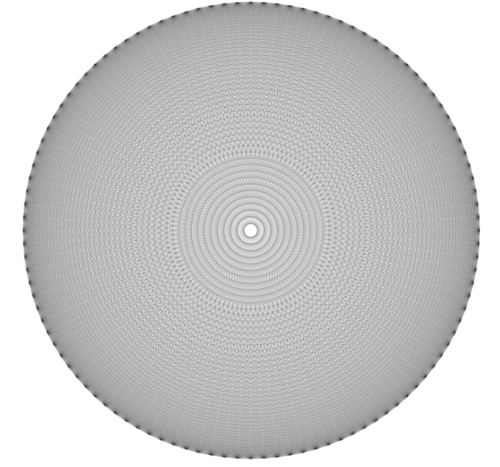

Jordan’s most recent project is E Pluribus Unum, 2010 24×24 feet, laser etched onto aluminum panels

From his website:

Depicts the names of one million organizations around the world that are

devoted to peace, environmental stewardship, social justice, and the

preservation of diverse and indigenous culture. The actual number of

such organizations is unknown, but estimates range between one and two

million, and growing. To decode the strands, click here and click on the image. (Via Eyeteeth)

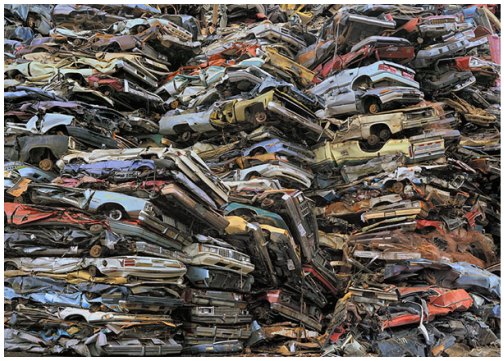

In 2004, Jordan photographed in a Seattle scrap salvage yard and printed the results large, 4 feet by 6 feet, aspiring to the kind of scale he’d admired in Andreas Gursky.

In 2004, Jordan photographed in a Seattle scrap salvage yard and printed the results large, 4 feet by 6 feet, aspiring to the kind of scale he’d admired in Andreas Gursky.

In Jordan’s mind, he was still following the thread of color bursting from trees.

His friend and fellow photographer, Subhankar Banerjee, saw the new print and said, “This is a portrait of America.”

The idea turned on the lights in Jordan’s head. From it came his giant prints of consumerist waste products. Rivers of cell phones. Mountains of crushed cars. Circuit board moonscapes and sawdust cathedrals. Worlds of scrap metal.

But even after the breakthrough, he was still just a guy with a camera.

But even after the breakthrough, he was still just a guy with a camera.

After trying unsuccessfully to get noticed in Seattle, he self-published a book and distributed it to every curator and gallery dealer he thought might respond. One did, Paul Kopeikin Gallery in Los Angeles. In 2005, at a dinner arranged by another dealer, Jordan found himself sitting next to New York Times editor and photography writer Philip Gefter.

In 2005, Gefter’s essay on Jordan’s work appeared on the front of the Sunday Arts and Leisure section, with a photo taking up nearly a third of the page. Jordan was a classic outside who created opportunity where there wasn’t one, but the force and clarity of his work, the audacity of the manipulated printing process, carried him into the future, documenting what he calls the “slow-motion apocalypse” of a use-and-discard society.

The drive behind his environmental subject matter is a memory of two boys turned into living torches by the side of river. His challenge is to avoid didacticism, and if he can’t, set it aflame. E Pluribus Unum catches him in a quiet and entirely celebratory mood. It won’t last.

Leave a Reply