But for him it was his last afternoon as himself, …

The current of his feeling failed; he became his admirers.

W. H. Auden

Poets matter to poets, musicians to musicians. Tributes to dancers come from other dancers. Rare are artists who inspire a legacy outside the arena of their endeavor.

Sixteen years after his death, the poet of power chords continues to matter to musicians, but the exhibition bearing his first name at the Seattle Art Museum isn’t about them. Curated by Michael Darling, it’s entirely about Cobain’s afterlife in visual art. Given the narrow theme, the breath of the work is astonishing: from robustly celebratory to tender, fierce to funereal, funereal to forensic. The exhibit opens with the artists who knew him, Seattle photographers Alice Wheeler and Charles Peterson. (Previous post here.)

Everyone else came after.

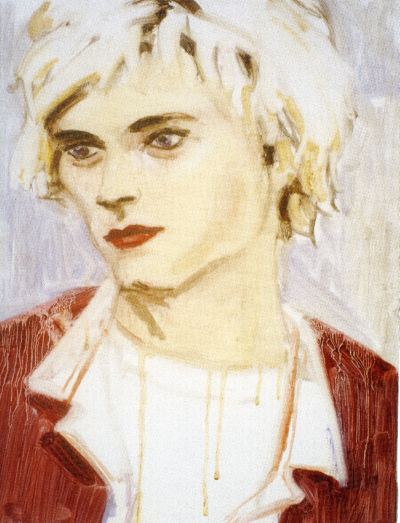

For Elizabeth Peyton, he’s a Russian icon remade in Oscar Wilde’s dandy mode: bloodless as an angel, lovely as a wilting wildflower. Cobain is her most consistent subject, and yet deliberately there is only one small portrait from her in the exhibit, a single piece given an entire wall for maximum impact. On it, painted silver, her colors glow. Derived from the thinnest of oils brushed onto heavily gessoed board and leaking in faltering streams, the painted molecules of her portrait appear ready to fall apart at the slightest touch.

If Peyton is the cooked, Scott Fife is the raw. His Cobain made of cardboard drilled with screws from a gun rests like a severed head on the ground.

If Peyton is the cooked, Scott Fife is the raw. His Cobain made of cardboard drilled with screws from a gun rests like a severed head on the ground.

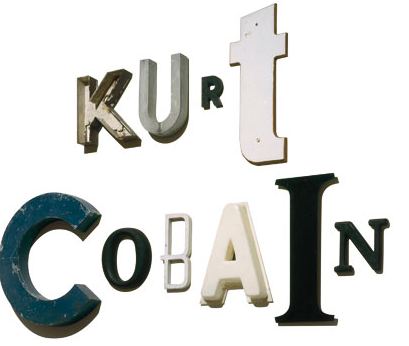

Jack Pierson offers the artist’s name in mismatched metal lettering, like a ransom note. (Kurt Cobain, 1994, 40 x 56 inches)

Jack Pierson offers the artist’s name in mismatched metal lettering, like a ransom note. (Kurt Cobain, 1994, 40 x 56 inches) The famous are their own tribe. They are interchangeable in their excesses and anonymous in their particulars.

The famous are their own tribe. They are interchangeable in their excesses and anonymous in their particulars.

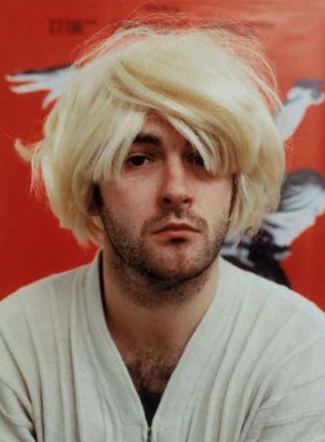

Douglas Gordon, Self-Portrait as Kurt Cobain, as Andy Warhol, as Myra Hindley, as Marilyn Monroe 1996.

From Heart-Shaped Box, the lyric, “Cut myself on angel hair and baby’s breath” inspired Joe Mama-Nitzberg and Marc Swanson‘s Untitled (Kurt Cobain), 2009. Wrapping the bouquet is part of a shirt from a French designer label Cobain favored after he hit it big. Turns out his flannel was not forever. Once the man had money, he wanted to look good.

From Heart-Shaped Box, the lyric, “Cut myself on angel hair and baby’s breath” inspired Joe Mama-Nitzberg and Marc Swanson‘s Untitled (Kurt Cobain), 2009. Wrapping the bouquet is part of a shirt from a French designer label Cobain favored after he hit it big. Turns out his flannel was not forever. Once the man had money, he wanted to look good.

Time slows around Banks Violette‘s Dead Star Memorial Structure (on their hands at last) from 2003. Why do brights lights insist on burning out? The sculpture is a drum-set wreckage shellacked in place, as if that wreckage were the point all along, the price to be paid for creating youth’s most haunting cri de coeur.

Time slows around Banks Violette‘s Dead Star Memorial Structure (on their hands at last) from 2003. Why do brights lights insist on burning out? The sculpture is a drum-set wreckage shellacked in place, as if that wreckage were the point all along, the price to be paid for creating youth’s most haunting cri de coeur.

Jordan Kantor is having none of that. His paintings of the death scene are both exact and unknowable. They chart the aftermath of violent death. Be it murder or suicide, fatal violence draws the cops. The people who bent over his body did not love it. For them, he was a professional puzzle to solve.

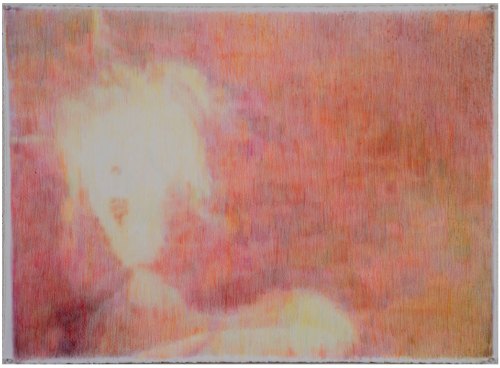

Drawn from Gus Van Sant’s Last Days as well as images from Internets, Gretchen Bennett‘s colored-pencil drawings have a bleached intensity, the subject drained in the spotlight’s glare, a private figure made of public moments.

Drawn from Gus Van Sant’s Last Days as well as images from Internets, Gretchen Bennett‘s colored-pencil drawings have a bleached intensity, the subject drained in the spotlight’s glare, a private figure made of public moments.

Jennifer West‘s film Come As You Are features her and her son jumping on a trampoline. Like Bennett, she’s interested in image decay as metaphor. Because for her Nirvana songs are all about expelling things from the body, she soaked her film in bleach, antacid, laxatives, mud and pennyroyal (all featured in Cobain’s lyrics) for a ruined celebration. (DVD

Jennifer West‘s film Come As You Are features her and her son jumping on a trampoline. Like Bennett, she’s interested in image decay as metaphor. Because for her Nirvana songs are all about expelling things from the body, she soaked her film in bleach, antacid, laxatives, mud and pennyroyal (all featured in Cobain’s lyrics) for a ruined celebration. (DVD

projection 16 mm film negative transferred to DVD. 2

minutes, 51 seconds)

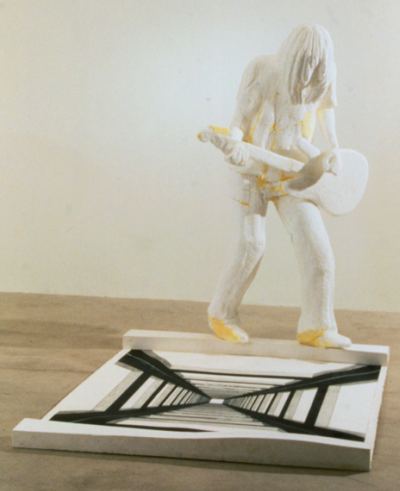

Evan Holloway‘s Left-Handed Guitarist, 1998, is made of foam, paper, plaster and graphite, but mostly foam. The figure bent over a guitar looks as if it’s made of Styrofoam that washed up on a beach. Cobain suffered from largely untreated back, stomach and intestinal problems. When he bent over his guitar in this posture, the intensity of the music was not the only reason.

Rodney Graham‘s unassuming slide installation, Aberdeen from 1998, plumbs the shallows of Cobain’s home ground, its bleak nowhere. The effect, slide after slide, is hypnotic. It’s a place where nothing will happen. The night will never fall, the car will never make it to the corner, and the kids who live there will not graduate from high school.

Rodney Graham‘s unassuming slide installation, Aberdeen from 1998, plumbs the shallows of Cobain’s home ground, its bleak nowhere. The effect, slide after slide, is hypnotic. It’s a place where nothing will happen. The night will never fall, the car will never make it to the corner, and the kids who live there will not graduate from high school.

And yet Cobain goes on. After his death, Alice Wheeler collected signifiers of his influence on the bodies of the young, including the dyed blonde guitarist kid who made his way to Seattle and pitched a tent on the outskirts of the city in 1999, wearing the flannel like a flag of his country.

Through Sept. 6.

Through Sept. 6.

Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,

And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections…