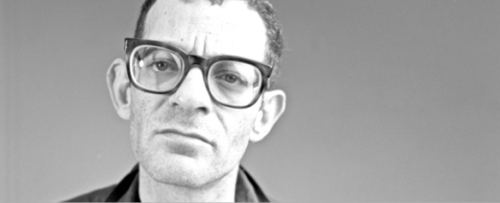

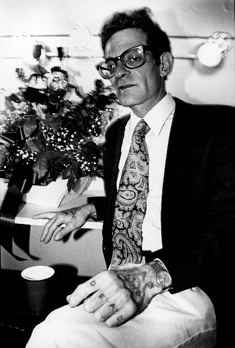

Speaking of himself in the third person, Jesse Bernstein once noted that he was “unemployed until the age of six; since then he has worked as a seeing eye dog for the spiritually impaired and as an emergency storm drain.”

Poet, performance artist, playwright, actor and friend of what he called the expendable people, he killed himself in 1990 in Neah Bay at age 40.

Photo Alice Wheeler

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Most of his friends remember him not for his tragedy, which included mental illness, alcoholism and drug addiction, but for his talent, his generosity, his steadfast loyalty and gleeful charm when the debilitating fog of illness lifted.

Small with bow legs and tattoos running up his arms, Bernstein had a

gravelly voice that became slurred when he neglected to put in his teeth

for his late-night phone calls to many willing and semi-willing

listeners.

They rarely needed to say anything. On the phone he said it all, ranging

across the history of poetics, the crimes of the Central Intelligence

Agency, the need for cheaper breakfast cereal and the search for a

sustaining form of God’s grace.

A well-edited collection of the range of his best work has yet to appear, although a posthumously released Sub Pop CD titled Prison briefly lit up the charts after selections from it played over the open sequence of Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers.

Peter Sillen’s recently completed documentary on Bernstein, I Am Secretly An Important Man, opens at The Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in North Carolina on Friday. It will screen as part of a Creative Capital film festival at the Museum of Modern Art on May 15 & 27. Sillen is still working on a Seattle release.

More Noise Please!

I live on a street

where there are many

many cars

and trucks

and factories

that pump

and bang and

grind all night

and day.

It is a miracle

that I can write poetry

or sleep or

talk on the telephone

or that

my lover will

visit me here.

There is

so much noise.

Every few minutes

a jet comes in low

or a prop job

swings down like

a kamikaze.

There is an airport

at the end of my street.

The new age people say

that you choose

all these things –

choose the cars

and trucks and

airplanes – me and

all of my neighbors.

Maybe this is true;

maybe we can’t live

without

all this goddam noise.

Maybe I need the noise

to write poems

make love and eat.

I’m going to hang a sign

out my window

that says:

More Noise Please!

or:

Thank You For Making Noise!

Maybe we are the kind of people

who need to have

what we don’t want

just to get along,

to do the basic things.

Myself,

I could not sleep

last night,

and I could not

close the window,

either. I tried

to tear the window

out of its frame

and put it

in a closed position,

banging and ripping

with the hammer

and a screw driver,

standing on the window ledge

in my socks

three stories up.

But, the window

wouldn’t come out

and the factory was screaming

and the trucks were rumbling

and the whole world

was praying for silence

and it was up to me

to shut the window

and I couldn’t

get it down.

I was just making

more noise.

A jet went by

and all the people waved.

Thanks, I yelled

as the shifts changed

without a lull in production

at the big plant

across the street.

The workers lined up

at the bus stop

watching me with my hammer

in the window.

I put sponge stoppers

in my ears,

but I can’t stand those things

for more than a few minutes.

Finally,

I put my head

between two pillows.

It is the same

every night.

I love it

I need it.

Without you I could not live,

I would not have written

this poem,

I yell,

the window dangling

half on half off.

Been listening to Prison while out on a road trip around the western states, he is missed, greatly…and loved eternally…