If you were going to get a pet

What kind of animal would you get?

A soft-bodied dog, a hen

Feathers and fur to begin it again

when the sun goes down and it gets dark

I saw an animal in a park

Bring it home to give it to you

I have seen animals break in two

You were looking for something soft

And loyal and clean and wondrously careful

a form of otherwise vicious habit

could have long ears and be called a rabbit

Dead died will die want

Morning midnight I asked you

If you were going to get a pet

What kind of animal would you get?

The Secret Language of Animals is not a secret. Instead, the exhibit of that title at the Tacoma Art Museum is almost entirely about us. Ever since humans stood up to look around, we’ve made images of animals as shipping containers addressed to ourselves. From the bull on the wall of a cave to the shark in a gallery, it’s a myriad-minded stream of us projecting into them.

The stream never ends, and neither does our interest. Through animal depictions, human consciousness parades. As a theme, it’s a hearty perennial, hard to kill. The good news is, Tacoma doesn’t. Curated by Rock Hushka, The Secret Language is, like his currently running A Concise History of Northwest Art, a winner.

Unlike A Concise History, however, The Secret Language is a baggy monster, drawn from the museum’s collection and beyond it, from the 19th century to the present. From its title to the structure of its categories arranged in zoo fashion, like with like, Hushka’s attempt to order his offerings fails to convince. What saves this exhibit are the objects in it. There are too many of them crammed together, but the grace and force of their diversity creates a gravitational pull of interest that sweeps the audience along.

There are three giant Deborah Butterfield‘s in one spacious gallery. Her horses are drawings in space. The best are lumbering but light, well bred from wreckage. These three are fine indeed. Why didn’t the museum give her the entire gallery? The small prints on the wall (Stubbs, Delacroix) are hedged bets. Hello Tacoma Art Museum: If you’re highlighting an artist, go ahead and give her the space. If she needs Stubbs to matter, she doesn’t.

Vanessa Renwick Longhorn, 2010

16mm to video loop

shot at Patty Pink Chap’s Ranch in Montana, from the Oregon Department of Kick Ass Renwick’s Longhorn is a rarity, a piece about an animal that offers nothing but the animal. Bill Viola’s buffalo breathing steam in the morning is an emblem of spirit, but Renwick’s shaggy star offers only itself. No meaning beyond its own adheres. With an economy of motion that makes sense in one so heavy-headed, it stares, turns, grazes and steps to the side, over and over in a repeating loop. It’s a massive utterance on a wide plain, and it has nothing to say to us.

Renwick’s Longhorn is a rarity, a piece about an animal that offers nothing but the animal. Bill Viola’s buffalo breathing steam in the morning is an emblem of spirit, but Renwick’s shaggy star offers only itself. No meaning beyond its own adheres. With an economy of motion that makes sense in one so heavy-headed, it stares, turns, grazes and steps to the side, over and over in a repeating loop. It’s a massive utterance on a wide plain, and it has nothing to say to us.

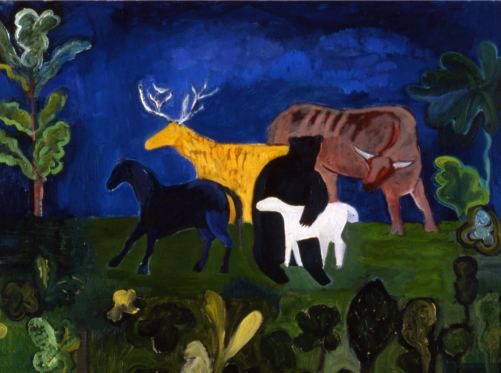

Elizabeth Sandvig‘s Peaceable Kingdom series was inspired, of course, by Edward Hicks. Unlike Hicks, she has no hopes of lions lying down with lambs, but she likes the lights and darks of their colored shapes and suggestive densities. Instead of family, the deer is as distant as the sun, and the black bear with a possessive paw on the flank of a sheep cannot be trusted.

Sandvig, Peaceable Kingdom at Night, 2003 oil/canvas 24 x 32 inches

Soaring past William Wegman’s dress-up dogs is Fred Muram‘s eating breakfast. The artist calmly dips his spoon around his dog’s lapping tongue and eats as if there’s nothing odd in doing so. He’s Buster Keaton who sees the train coming but doesn’t leave the tracks. Muram divides the world in two: those who know a train with a tail won’t hurt them and those who are fearfully freaked out.

Soaring past William Wegman’s dress-up dogs is Fred Muram‘s eating breakfast. The artist calmly dips his spoon around his dog’s lapping tongue and eats as if there’s nothing odd in doing so. He’s Buster Keaton who sees the train coming but doesn’t leave the tracks. Muram divides the world in two: those who know a train with a tail won’t hurt them and those who are fearfully freaked out.

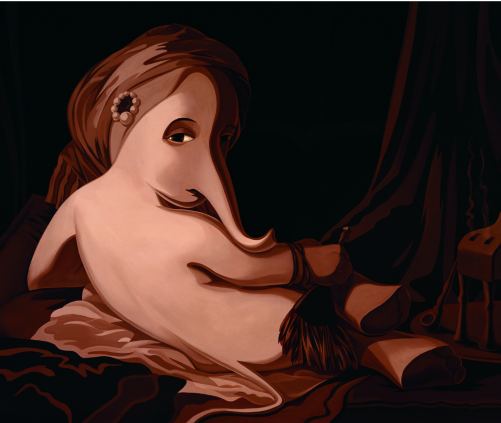

Muram Sharing a Bowl of Fruit Loops with My Dog, 208 Single channel video Dimensions variable In monochromatic sepia, Joseph Park‘s The Grand Odalisque takes

In monochromatic sepia, Joseph Park‘s The Grand Odalisque takes

Ingres’ boneless paintings of nude women (all flesh, little

structure), and sets not only the figure but the ground

around it in motion. Curtain, bed, tassel, turban, tail and trunk have a seamless flow. It’s a lost time looked at again with humor and a

strange, silky gravity.

Park, The Grand Odalisque, 2001 oil/linen 30 x 36 inches

I’m not sure that Malia Jensen‘s bronze bear would matter much without its title. With it, the animal is the epitome of a guilty party, confessing only when caught.

I’m not sure that Malia Jensen‘s bronze bear would matter much without its title. With it, the animal is the epitome of a guilty party, confessing only when caught.

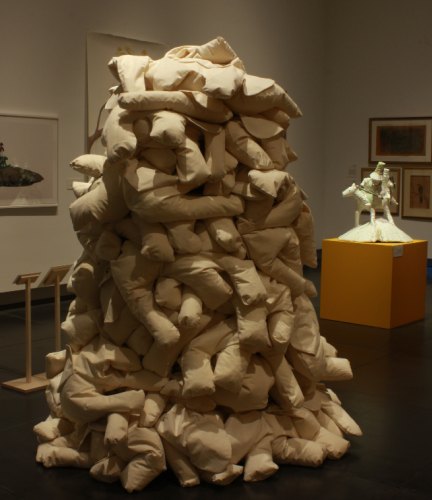

Jensen, Is This Your Cat? 2006 Bronze 22 x 14 x12 Hats off to Hushka for recreating Jeffry Mitchell‘s elephant pile from 1990, sewn by Tacoma Art Museum volunteers. Let’s hear it for battered hopes and dreams, for what goes soft and slack and lies discarded in a sweet heap.

Hats off to Hushka for recreating Jeffry Mitchell‘s elephant pile from 1990, sewn by Tacoma Art Museum volunteers. Let’s hear it for battered hopes and dreams, for what goes soft and slack and lies discarded in a sweet heap.

Mitchell, The Pile of Elephants, 1990 recreated 2010 Muslin and Styrofoam, 114 x 108 x 108 inches. (Claire Cowie’s Villagers on Horse, 2004-05 in the rear)

Richard Hart paints marsupial girls.

Richard Hart paints marsupial girls.

Hart The Poetic Truths of High-School Journal Keepers, 2009

Maki Tamura‘s painted paper constructions can be overworked. Not this one, whose image fails to do it justice. The incredible lightness of its being evokes Fragonard.

Maki Tamura‘s painted paper constructions can be overworked. Not this one, whose image fails to do it justice. The incredible lightness of its being evokes Fragonard.

Tamura Circus 2009 watercolor paper Geoffrey Chadsey‘s paintings cannot be reproduced. Missing is the queasy subtly of the shading, the face and chest whorled like diseased tree rings, the way the small dog is actually more of a rat resting on the root of a cadaverous man.

Geoffrey Chadsey‘s paintings cannot be reproduced. Missing is the queasy subtly of the shading, the face and chest whorled like diseased tree rings, the way the small dog is actually more of a rat resting on the root of a cadaverous man.

Chadsey Pet 2010 watercolor pencil on Mylar

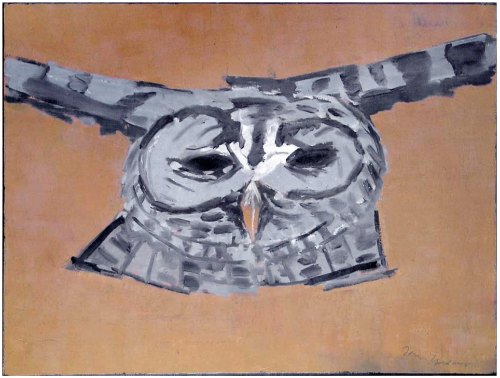

Air, desert, blue owl:

Air, desert, blue owl:

Joseph Goldberg Chaco 2005 encaustic on linen over wood 36 x 48 inches

Nice to see Justin Gibbens‘ birds hanging with one of Audubon’s, their source. Also worth the trip in this show are the Joan Brown’s, Muarizio Cattelan’s taxidermized dog sleeping in a chair (Good Boy, 1998); Morris Graves’ Walking Bird, 1943; John Baldessari’s Two Onlookers and Tragedy (With Mice) 1989; Kenneth Callahan’s dragonfly, late 1950s; Nole Giulini’s Mickey Mouse Organ, from 1994, several Claire Cowie’s, and Alden Mason’s Polka at the Public Market, 1987.

Nice to see Justin Gibbens‘ birds hanging with one of Audubon’s, their source. Also worth the trip in this show are the Joan Brown’s, Muarizio Cattelan’s taxidermized dog sleeping in a chair (Good Boy, 1998); Morris Graves’ Walking Bird, 1943; John Baldessari’s Two Onlookers and Tragedy (With Mice) 1989; Kenneth Callahan’s dragonfly, late 1950s; Nole Giulini’s Mickey Mouse Organ, from 1994, several Claire Cowie’s, and Alden Mason’s Polka at the Public Market, 1987.

Post to follow: the downside.

Leave a Reply