Hat hip to New York Times’ critic Ken Johnson for his Viola Frey review, which challenges conventional opinion by pretending it isn’t there. Why not? It’s his review. He can use all his space for what he’s thinking.

Viola Frey’s giant ceramic sculptures of men and women are among the underappreciated wonders of late-20th-century art. Rising 11 feet and higher, wearing business suits and ties and nondescript dresses, they have a spookily imposing physical presence and a clunky, cartoonish ugliness.

Roughly glazed in strident colors and made in sections that fit together like blocks in a stone wall, they could be mistaken for a species of Outsider art. Because of their size and their blank or seemingly angry expressions, they may remind you of what it was like to be a child among grown-ups troubled by incomprehensible problems. (more)

I share the conventional view, that her work was the same thing over and over, that she was a kind of folk artist living in the eternal present. Viewed in the context of mainstream contemporary art, she had nowhere to go and didn’t manage to get there.

Although he calls her a “true original,” he locates her among her peers, where her work falters. On the other hand, besides the artists mentioned below, he throws in Joan Brown and Robert Crumb.

Although he calls her a “true original,” he locates her among her peers, where her work falters. On the other hand, besides the artists mentioned below, he throws in Joan Brown and Robert Crumb.

Robert Crumb? I’d love to see Crumb and Frey together in a gallery. Crumb would be the kind of excellent sideman who makes a questionable soloist look good. Johnson’s review doesn’t change my mind, but thinking about the Crumb-Frey combination begins to. Stranded in her own company, she’s like a lonely person talking to a mirror. (No was all she said.)

A resident of San Francisco for most of her adult life, Frey belonged to a generation of artists who made ceramic sculpture a force to be reckoned with in the 1960s and ’70s. Peter Voulkos started the revolution in the late ’50s with his raw, nonrepresentational clay works made in the spirit of Abstract Expressionism. Robert Arneson’s jokey narratives and Ken Price’s small, adamantine abstractions expanded the field.

Putting her work in a room with that of the endlessly inventive Robert Arneson or the “adamantine” (good word) Ken Price would do her no favors. Who else in West Coast clay from the 1960s and 1970s could use the Crumb assist?

Not the Rabelaisian Howard Kottler. He belongs with Robert Arneson, who would not be able to wipe the floor with him. (Image via)

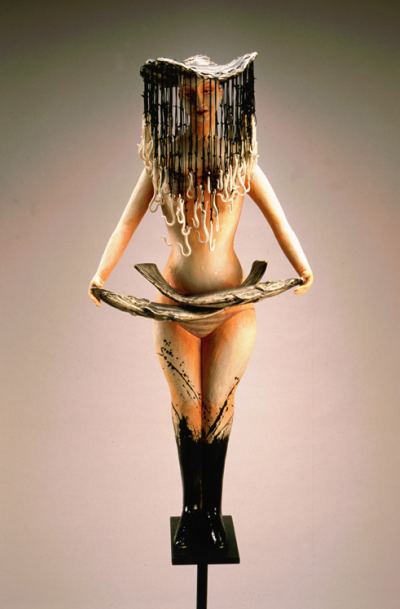

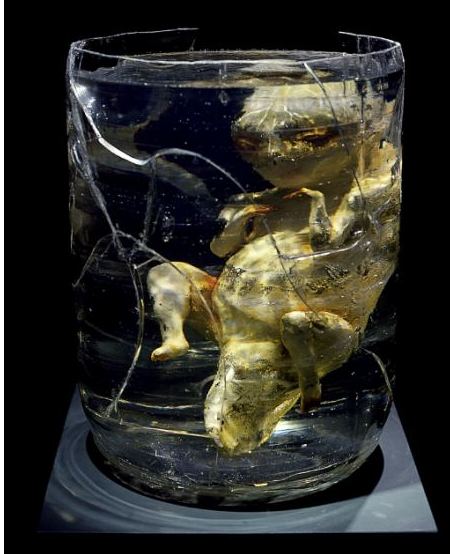

To Crumb and Frey I’d add Patti Warashina…

To Crumb and Frey I’d add Patti Warashina…

And Lauren Grossman. (Like Warashina, at Howard House.)

And Lauren Grossman. (Like Warashina, at Howard House.)

Grossman was just starting out in the 1970s, but she would not only shine in a Crumb-Frey-Warashina exhibit, she’d make the others shine too. She’d bring out both the mournful melody of the collective theme and the relish in its depiction.

Grossman was just starting out in the 1970s, but she would not only shine in a Crumb-Frey-Warashina exhibit, she’d make the others shine too. She’d bring out both the mournful melody of the collective theme and the relish in its depiction.

Some artists do best alone. Others need a crowd. Most need the kind of curatorial and critical attention that allows them to be the best version of themselves, to make the case that they do not deserve to be forgotten. In seeing past the opinions of others, Ken Johnson has begun the work necessary to keep Frey’s legacy alive.

perhaps Red Grooms would make another informed comparison within the context of her work and others mentioned too.

Erin. Yes. Red Grooms and Viola Frey. You’re hired to curate.