A container is not the thing contained. It’s a prop instead of an essential, except in the work of Brooklyn’s Jennie C. Jones.

Jones:

My practice is both a comment on and a continuum of the conceptual ideology of jazz, an honoring of the deep radical legacy of its experimentation, of hybrid modernist forms, of wit, of riff — the turning of a phrase onto itself.

Her sculptures and drawings are improvisations on the cassette tape, transistor radio, boom box, Walkman, from intimate long play to the impersonal present. In her hands, old style records with their pop and fizz beat the immaculate conception of new style downloads. You can’t hold a download in your hands. Downloads move from computer to ear bud without taking your body into account, your care or disregard, how you treat your cultural legacy.

Formally, her work is subtle, with a wit that does not translate online. There, her work becomes one thing. In person, it’s myriad-minded.

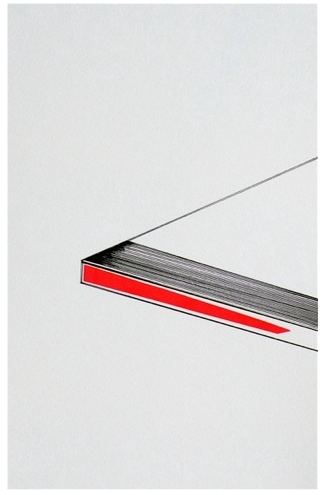

Top 100 jazz Lps 1969-79, (2010)

Paper, cassette cases, plywood, album list presented as title card.

18 x 24 x 3 in.

Top 100 jazz Lp’s 1969-79

Top 100 jazz Lp’s 1969-79

has a one-two punch. First, it’s a primary structure – Donald Judd-like with a backbeat of the domestic. A second look delivers the literal. It’s a homage to cassette tapes, a mimicking of their form for abstract effect. Online, the piece looks like a photo of an industrial kind of window shutter.

Holland Cotter called Jones’ installation, Homage to an Unknown Suburban Black Girl, one of the highlights of Freestyle at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001.

Cotter:

Based on a found snapshot of a young black girl sitting in what looks like a suburban interior, the piece focused on how two different strands of African-American history coexist in a single picture.

One history is of assimilation, implied by the middle-class setting. The other, suggested by the girl’s Afro hairstyle, is of Black Power politics, which arose in response to a racism that integration alone could not change. In short, in Ms. Jones’s reading, the photograph was a document of people who remained, consciously or not, tolerated guests in the house — American culture — that they had helped to build.

In the same review, he described Jones’ sculptural foray into Bebop at Artists Space as “even subtler.”

Cotter:

This time the document she presents is aural: the sound of Charlie Parker’s music as informally recorded by another saxophonist, Dean Benedetti, who was obsessed with Parker’s life and art. The tapes surfaced in 1988 and were regarded as treasured relics despite their poorly recorded and distorted sound.

In the gallery, an edited version of the recordings plays from two large speakers, and small collage-drawings by Ms. Jones hang on the wall. At first glance, the drawings are classic Modernist-style abstractions composed of squares and rectangles. But wirelike black ink lines that emerge from the geometric forms turn them into something else: clusters of tiny microphones or speakers.

Positioned around the room, they seem to be at once recording and projecting Parker’s music, music that is, Ms. Jones seems to suggest, not a distorted ghost from the past or the obscure object of someone’s desire, but the very sound of Modernism itself, loud, clear and everywhere.

Common objects she burnishes into relics, like slivers of the True Cross:

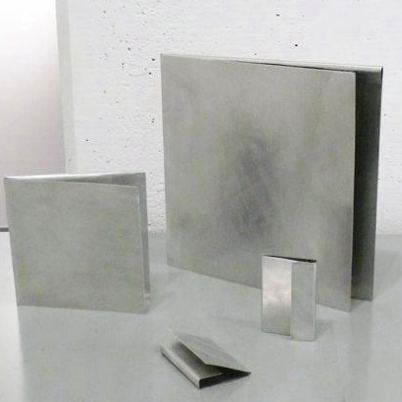

Blanks (45, LP and cassette liner notes), (2007)

Hand-brushed aluminum Artist Proofs.

To be editioned in stainless steel with an additional 8-track sleeve.

What is the shape of musical memory?

What is the shape of musical memory?

from Blank series, 2009-10, collage and ink on paper

To March 27 at Lawrimore Project.

To March 27 at Lawrimore Project.

/Im down with Jennie C Jones, Great Show/