The art world is always saying next, please. I’m bored with your dead tiger shark and live nudes, your singing museum guard and your fallen Pope. The shark that is never dead is the art world itself, which, as Woody Allen explained in Annie Hall, has to keep moving to stay alive.

Those who work in that world shovel the present into the past as a kind of necessary clean-up. For market reasons disguised as aesthetics, key power players determine who among the previously celebrated remains a live wire. The rest will be regulated to the heap of has-beens, to be humiliated and disappeared. Only live wires make the market hum.

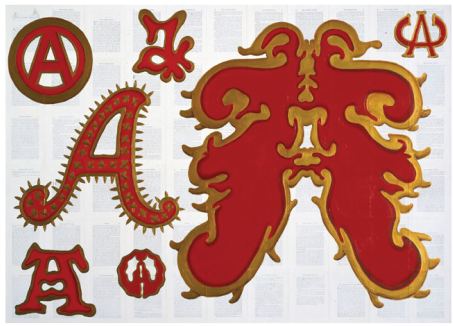

Even as they rose like surface to air missiles to art world’s stratospheres, Tim Rollins and K.O.S. lived with an undertow of detractors, those who thought somebody was being exploited here and it could well be them for taking this project seriously.

How could it be taken seriously? The odds against it are impossible.

In 1981, when collectors were drinking pink champagne out of glass slippers at the Mary Boone Gallery, a serious student of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., John Dewey and Joseph Kosuth stepped off the subway in the South Bronx to the smell of the burning garbage.

In 1981, when collectors were drinking pink champagne out of glass slippers at the Mary Boone Gallery, a serious student of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., John Dewey and Joseph Kosuth stepped off the subway in the South Bronx to the smell of the burning garbage.

From James Romaine, an essay in the catalog for Tim Rollins and K.O.S – A History:

Rollins

walked the four-and-a-half blocks to the school through a decimated

landscape of burnt-out buildings and vacant lots strewn with trash and

urban rubble, roamed by packs of wild dogs, with the remains of

Santeria animal sacrifices in front of crack houses. He also saw

mothers walking their children to school.

His job

became teaching art in special education classes at I.S. 52. Special

education, in this case, turned out to be a dumping ground for

discipline problems and dyslectics. One of the reasons there are so few

girls in the K.O.S. relates to this original structure. Discipline

problems are boys, and so are dyslectics. Once Rollins was established,

the dumping ground premise still operated for educators making

referrals. The students who were failing their classes but drew

imaginary worlds in their notebooks were male.

Rollins:

We

had three or four girls, but the boys created an environment that was

sometimes hard for the girls. This is not the Brady Bunch and in that

particular machismo culture, it was sometimes rough for them. Their

parents also put more constraints on the girls that the boys didn’t

have.

On the first day of his first class, Rollins

told the students that they were going to make art and also make

history. Nearly 30 years later, they are still at it, generations of

them becoming teachers and artists themselves and Rollins, the maestro,

still conducting this unlikely orchestra into greatness.

What

What

Rollins continues to demonstrate is not that a few individuals can beat

the odds. No, what he proved is that the art world is not a shark. It’s

a sea in which sharks and other forms of life move. He and his

students, current and former, invite us to join them in this wider

realm.

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. – A History

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. – A History

was organized by Ian Berry of the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum

and Gallery at Skidmore College. Robin Held brought a choice portion of

it to the Frye Art Museum, where

it continues through March 21. If you’ve ever been depressed about the

possibilities of positive social change and/or the exclusionary

structure of the art world, see this show, buy the catalog and watch the documentary. Up and at ’em, people. Up and at ’em.

Leave a Reply