From an anonymous source going by the name of Not Buying It in response to the post titled, Mary Henry – artists hidden in plain sight:

Neglected abstract geometric artists are plentiful? Are you talking about painters who deserve to be well known? Name five. Not just anybody, but somebody who has created work that could stand up to international attention. The artists at the top aren’t there by luck. They are better than the obscure. I’ve never heard of Mary Henry. Her work looks pretty good online, but online is nowhere as you must know. There must be a reason why it doesn’t fly when seen in person. If not, it would have.

Ordinarily, I don’t single out comments from someone who chooses to be anonymous, but I like this issue, if only because the idea that there are only three or four artists who matter in a generation is gaining ground. (The Onion‘s disquisition on the theme here.)

Jerry Saltz, lamenting it:

… instead of the love spreading and everyone becoming “famous for 15 minutes,” by decade’s end art-worlders fixated on a tiny clique of mostly male, mostly high-priced artists: Murakami, Hirst, Eliasson. Warhol’s dictum was infernally inverted to “In the future, only 15 people will be famous.”

You don’t need a weatherman to know that some people don’t like to go outside. Anybody who believes a handful of artists represents the world doesn’t care about art. If a focus is narrow enough, the only thing visible through its aperture is hierarchy. Art is about invention, possibility, rigor and surprise. Artists who rise to the top have all that and something else besides: the luck of the draw. For their representations of their place and time, they manage to become visible, frequently due to circumstances beyond their arranging.

My favorite fall-into-fame story is Charles LeDray‘s, which I’ve told before, here. To recap: He was born in Seattle in 1960 and raised here. His mother taught him to sew at age 4. By the time he was 10, he could sew, knit and macrame with a skill that staggered his elders. He took at the craft classes he could at the Queen Anne Community Center and endured the sexual taunting frequently hurled at boys who’d rather sew than play hoops or hang out at arcades.

LeDray, Grey Area, 2009

After high school, he took a couple of painting classes at Cornish College of the Arts but didn’t complete them. He worked as a guard at the Seattle Art Museum in the mid-to late ’80s and had a single exhibit of paintings at the Broadway Espresso in 1983. That’s it, aside from the time he tried to show tiny figurative collages on the sidewalk during Pioneer Square’s First Thursday Gallery Walk. The police, seeing gay porn, told him to pack up and leave. If anyone else noticed, there is no record of it.

After high school, he took a couple of painting classes at Cornish College of the Arts but didn’t complete them. He worked as a guard at the Seattle Art Museum in the mid-to late ’80s and had a single exhibit of paintings at the Broadway Espresso in 1983. That’s it, aside from the time he tried to show tiny figurative collages on the sidewalk during Pioneer Square’s First Thursday Gallery Walk. The police, seeing gay porn, told him to pack up and leave. If anyone else noticed, there is no record of it.

The silence surrounding him in Seattle was resounding.

In 1989, planning to try his luck in New York, he asked SAM’s director of exhibition design, Michael McCafferty, to write a recommendation. Bear in mind that LeDray was a guard, not even a part-time member of McCafferty’s design crew. Nevertheless, McCafferty whipped out a piece of museum stationery on which he scribbled a note to the effect that LeDray was a valuable member of his team and recommended him unreservedly.

After dropping his duffels at a friend’s apartment, LeDray headed over to the Museum of Modern Art, where he presented McCafferty’s introduction. That afternoon, he was handling MOMA’s Van Gogh’s.

When, years later, I asked McCafferty about this incident, I wondered if he sensed LeDray’s latent potential. Did he think LeDray had the makings of a major artist, in other words?

No, said McCafferty. Back then, I thought of him mainly as a collector of Space Needle memorabilia.

McCafferty believes in recommending people. They ask, he says yes.

Back to LeDray. The freelance job at MOMA led to a job as art handler at the Jack Tilton Gallery. One day he noticed the objects in an upcoming exhibit had a link with what he made on his own at home to relax. Gallery director Janine Cirincione told him to show her. He brought in a bear in a jacket. She told him she couldn’t use the bear but the jacket would do nicely.

Hours before the show opened, she added LeDray, whose career took off.

Obviously, he had to be remarkable to turn McCafferty’s blind recommendation into a career, and LeDray is. He’s now a leader in what could be called the “Revenge of the Maker” movement, a corrective to the equally valid Call-It-In School. Without a series of fortunate accidents, however, would he have had the opportunity to be heard or would he have been the fabled tree whose fall in a forest attracted no witnesses and therefore made no sound?

Not Buying It asked for five artists who have worked in the abstract geometric vein and deserve a wider audience.

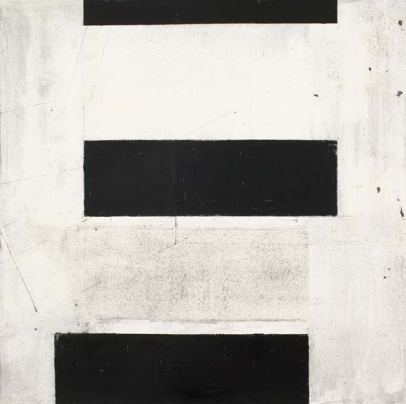

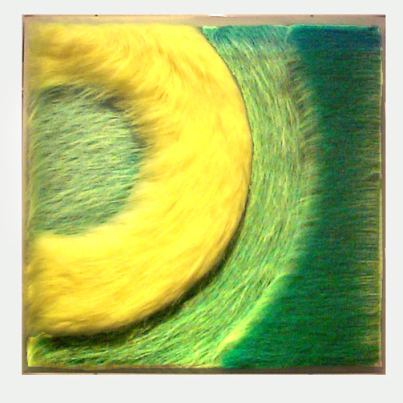

1. Robert Yoder (Low Tide, 2004)

2. Yunhee Min (FP(—)a, 2008)

2. Yunhee Min (FP(—)a, 2008)

3. Lauri Chambers (Untitled, 2008)

3. Lauri Chambers (Untitled, 2008)

4. Sean Duffy (Untitled, 2001)

4. Sean Duffy (Untitled, 2001)

5. Peter Millett (Purple Window, 1991)

5. Peter Millett (Purple Window, 1991)

That designer at the museum did Charles LeDray a good turn. One good turn leads to another. The reverse is true too. It comes down to who you know and who you can count on. After that, it’s who you are and what you do. Whether people like it depends on whether they’re primed to like it, whether it makes sense in terms of their lives. If artists don’t have the right friends or patrons or whatever you want to call them, it doesn’t matter what the work is.

What about Carmen Herrera, recently featured in the NY Times? http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/20/arts/design/20herrera.html?scp=5&sq=abstract%20geometric%20painting&st=cse

Hi Heidi: The post you read was a response to an earlier post on this blog about Carmen Herrera, http://www.artsjournal.com/anotherbb/2009/12/mary-henry—artists-hidden-in.html