In her 30s, having destroyed all student work, Fay Jones started painting tiny, folkloric scenes on her kitchen table. She used tempera for a while, tried oil paints and didn’t like them.

In a 2005 interview, she explained her preferences for acrylics and watercolor.

What other people like about oil I don’t. It dries slowly. Others like the brush against the canvas. I hated to wait for the paint to dry. My paintings were mud. There’s no romance to acrylics, but they’re fast and worked for me right away. Oils have a life of their own. With acrylics, you have to mix them to get good colors. For me, watercolors are a sensuous experience. They are as close as I come to romance in the process.

By the late 1970s, she began painting larger than her hand’s span but continued to work on paper. She made the leap to life-size figures after she realized she’d figured out everything she needed to know to work small.

I wanted to go beyond what I knew. I don’t plan my work in advance. I figure it out as I go. The formal qualities that make the painting click I find as I’m working. When a painting is larger than I am, I have to keep moving. Everything changes. The eye stays in motion, and I feel freer.

My paintings are weightless. When they’re weightless, they’re mine. I could roll 10 years worth of painting in a tube and carry it.

In the 1980s, Jones was the most influential painter in the Northwest.

Her weightlessness ruled the region, supplanted in the 1990s by Darren Waterston (organic goo) and Robert Yoder (battered geometries). Followers come and go, but these three sources continue to flourish.

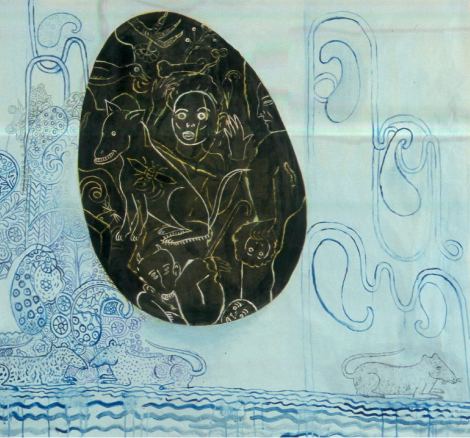

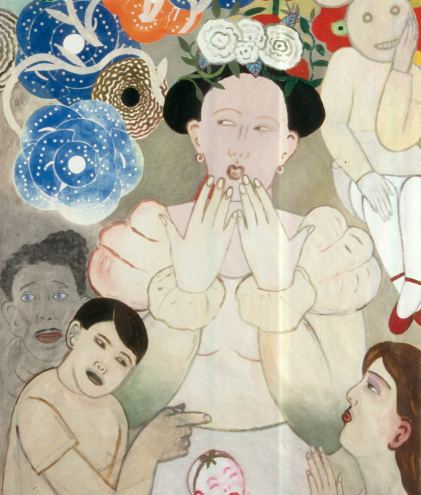

Now on view at Grover/Thurston,

Jones has continued to whittle away at her narratives. She still has a

storyteller’s heart, but what’s left are emblems of those stories, as

if birds had eaten the breadcrumbs leading out of her narrative forest.

Men continue to be missing even when

they’re there. They are ghosts, distractions and victims of

tunnel vision: long darks for women to whistle through.

Her new

work is all about hands. Supporting her cast of women in charge and men

in shadow, her losses and love of the mutable world, are a chorus of

hands. They signal her own approach, how she finds her way into each

scene, not with a plan but the plan her hand reveals as she makes it.

Through Dec. 19.

Through Dec. 19.

Are you suggesting Fay Jones’ influence waned after the 1980s? I don’t think that’s true. I moved to Seattle in the late 1990s and saw imitations of her everywhere.

No, I’m not. But by the middle of the ’90s, imitations of other painters were also noticeable.