Narratives encased in convention become fluid in The Old, Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art, inviting the audience to appreciate what Laura Lark called in her excellent review the “complexity of the iconic.”

Organized by Toby Kamps, senior curator

at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the exhibit opened there

in May, 2008, and debuted at the Frye Museum on Saturday. It features 18 young to mid-career artists interested in the roots of an American experience that extends from the Pilgrims to the Space Race.

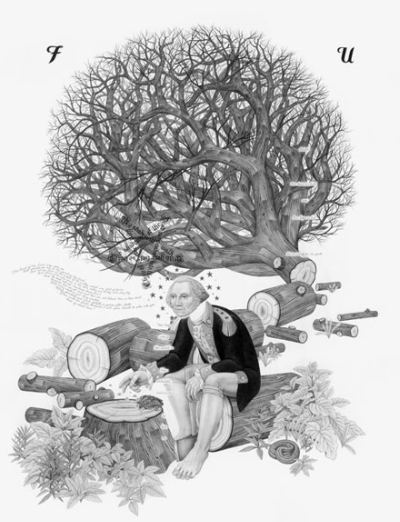

Eric Beltz, Fuck You Tree, (detail), 2007, graphite on board, 40 x 30 inches

Beltz gave the father of our country lovely feet. If he could stand, they could carry him out of this scene of morbid self-reflection. Instead, he sits on a log from his cherry tree with stars from the original 13 colonies ringing his face like mosquitoes, and his head detached from his body as if ready to be reproduced on dollar bills. The tree itself flourishes behind him as a rootless cosmopolitan, an entangling alliance.

Beltz gave the father of our country lovely feet. If he could stand, they could carry him out of this scene of morbid self-reflection. Instead, he sits on a log from his cherry tree with stars from the original 13 colonies ringing his face like mosquitoes, and his head detached from his body as if ready to be reproduced on dollar bills. The tree itself flourishes behind him as a rootless cosmopolitan, an entangling alliance.

The title of the show comes from the peerless Greil Marcus, who used it for his essay on Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, in which Dylan paid homage to American blues and country folk.

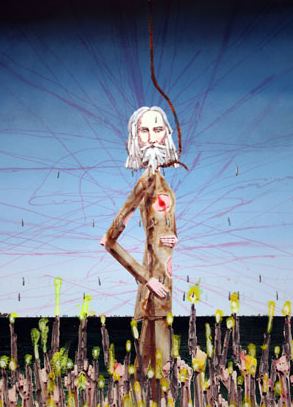

Barnaby Furnas’ paintings are a giant step up from Ralph Steadman’s illustrations, which could be a source. Where Steadman relies on endlessly repeated flat splatter, Furnas opens the splatter with electric Kool-Aid colors, scale shifts and the narrative detachment of video games.

When James Baldwin was asked in the late 1950s if there were a candidate he could support for President, he answered, “Yes. John Brown”. The guns firing at Brown’s feet are candles and also flowers reminiscent of Anslem Kiefer’s.

Furnas, John Brown, 2005, Urethane/dye on linen, 72 x 60 inches.

When heads explode, you can almost hear the “ping” of points scored.

When heads explode, you can almost hear the “ping” of points scored.

Strewn

Strewn

across the galleries are Allison Smith’s Civil War mannequins.

Exhausted or dead, all feature versions of the artist’s face.

Kara

Kara

Walker explores the metaphoric possibilities of shadow worlds. Since

her debut in the 1990s, they have become omnipresent, and yet their

internal rigor keeps their edges sharp.

Walker, Video still from 8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture, 2005

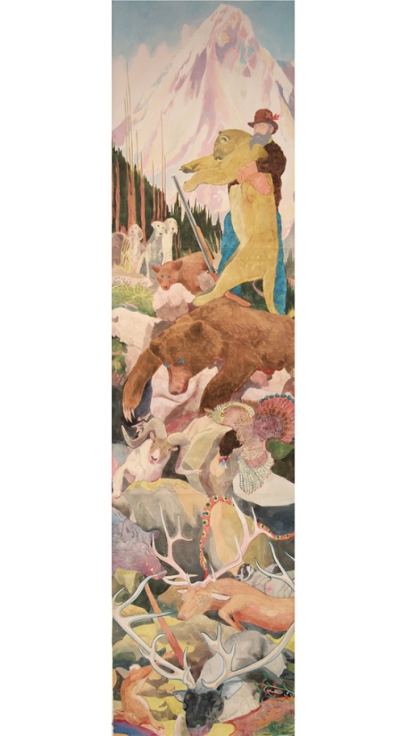

Space is accordion in the acrylic paintings of Aaron Morse, who turns the known world inside out.

Space is accordion in the acrylic paintings of Aaron Morse, who turns the known world inside out.

Morse, The Good Hunt (#2), 2006, acrylic, watercolor, pencil on paper, 90 x 22 inches

Deborah

Deborah

Grant’s hieroglyphic storyboards are a homage to the austere imagery of

former-slave Bill Traylor. He is her history, her tale to retell.

Grant, Where Good Darkies Go, 2006 acrylic/birch panel

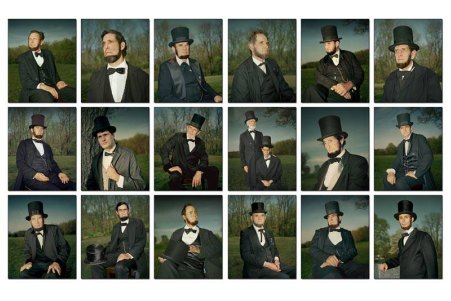

When

When

Americans look backward searching for light, many see Abe Lincoln.

Dissatisfied with the historical remove, some want to be him, as if he

were Elvis, forever coming back from the dead.

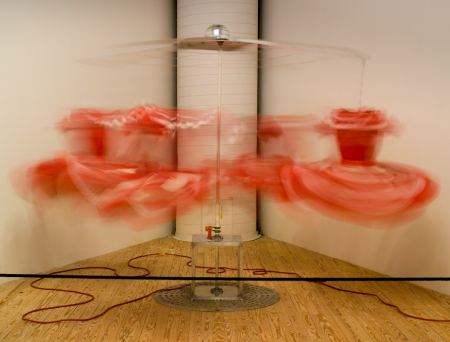

Greta Pratt, Nineteen Lincolns, 2005 Before

Before

they collectively took to their couches to watch Jerry Springer and Fox

News, rural Americans went dancing. Even as those who wore them aged,

dresses continued to flair over a frozen flourish of petticoats.

Cynthia Norton, Dancing Squared, 2004

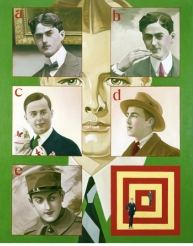

McDermott

McDermott

& McGough honor the dandy, the pioneering gay emblem who defied a

culture that considered homosexuality a crime by living well.

McDermott & McGough, Divine Fury, 1932, 2002, oil/linen, 60 x 48 inches

Charlie White, 1957, 2006, C-print, 44 x 56 inches

Charlie White, 1957, 2006, C-print, 44 x 56 inches

Appropriated

Appropriated

from a myriad of sources, including Norman Rockwell’s illustration of

Ruby Bridges marching into a segregated New Orleans school (that’s her

on the far left), White’s tapestry collage has a flat, unnaturally even

light, as if history, at this turning point, were holding its breath.

Also

terrific in this show are Jeremy Blake’s cloudy mixtures of memory,

guilt and loss; Matthew Day Jackson’s post-Rauschenberg book of

photographic imagery trailing across a wall like a diagrammed sentence,

and Brad Kahlhamer’s rush of signs and symbols hurtling across the

paper like a river intent on a flood.

Dario Robleto continues to elude me. Much is made of his ability to forge objects out of a cacophony of sources. His Rosary for Rhythm derives from melted and carved vinyl records of Jerry Lee Lewis’ and Little Richard’s “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.”

That’s

swell, but in the end what Robleto delivers are ….rosary beads. I’ve

seen them before. Lots of times. They rattle through my dreams like the

ghost of Christmas past. What has Robleto added? I’d say nothing.

Through

fetishistic processes he arrives at the commonplace, and his dainty

chests of drawers are not worth opening. (Boston Globe art critic Sebastian Smee disagrees, finding Robleto’s contributions to this exhibit “eye-popping” and “brilliant.”)

(Earlier post on Sam Durant’s contribution to this show here.) The Old, Weird America runs through Jan. 3. Free admission.

Great review. I’m ditto on Dario. So what if he uses the eye of a newt and the tongue of a dove? None of its flies.

You did a great review! Unfortunately it is over in 2010 ?