In a video at Western Bridge, one child reads from Bill Clinton’s welfare reform speech as others unwrap what prove to be empty boxes in a rapid-fire blur.

“Work organizes life,” observed Clinton, ringing the wrong bell.

“Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work will set you free”) was on a sign over a Nazi death camp.

Even without a Nazi echo in a piping voice, Clinton’s plan assumed a fantasy, as DailyKos noted, that “hard work stocking shelves will lead Wal-Mart to pay you more than $7.50 per hour.”

Maria Marshall’s President Bill Clinton, Memphis, Nov. 13, 1993 charts a Sisyphean cycle. Unwrapping nothing reverses into clean-up before rolling on again. Still, the idea that the work parents do (or don’t do) influences their offspring is undeniable.

Maria Marshall’s President Bill Clinton, Memphis, Nov. 13, 1993 charts a Sisyphean cycle. Unwrapping nothing reverses into clean-up before rolling on again. Still, the idea that the work parents do (or don’t do) influences their offspring is undeniable.

Marshall is part of Parenthesis, an exhibit that examines the connective tissue between parents and children. It’s art made from life’s glue.

Because Parenthesis is largely video, its curator (Western Bridge director Eric Fredericksen) worried that sound overlaps would produce a muddle. Instead of retreating to headphones, he hired theater designer Jennifer Zeyl to shape the space to contain individual sounds as well as enlarge the theme.

She created a house with the trappings of home, based on the upper-middle class tract version she grew up inside. (Photo via Best Of)

Before you enter, you’re already inside, having passed by Ann Hamilton’s video Still 3 from 2001 inset into a wall by the reception desk. Still 3 is small and easy to ignore, but once you stop, you’re hooked. It features a mother’s voice as she examines an ultrasound video of her baby.

Before you enter, you’re already inside, having passed by Ann Hamilton’s video Still 3 from 2001 inset into a wall by the reception desk. Still 3 is small and easy to ignore, but once you stop, you’re hooked. It features a mother’s voice as she examines an ultrasound video of her baby.

I think a lot of the very abstract quality of my work – and the literal

quality of it – is always dealing with a state or a place or an edge, a

border, a threshold, a place that’s in between. (more)

Behind the Hamilton are a cluster of terrific photographs: Kerry Tribe‘s Dad’s Books, My Film Equipment from 2006; Sally Mann‘s Burgers from 1988, when her children were young; Matthew Cox’s impenetrable Family Portrait, shot in 2008 on a digital camera with the lens removed, and Tina Barney‘s The Son from 1987.

Instead of Barney’s usual Upper East Side Manhattan wealth, she offers Upper West Side intellectuals, and yet the subject is the same: parents and children. (Image via) What could this kid have done to be subject to such heat? Missed an appointment with his S.A.T. coach?

Back

Back

to Zeyl: On the other side of Zeyl’s front door is a living room. In

front of a deep-dish couch is a video screen on a wide coffee table.

Playing on the screen are Neil Goldberg‘s My Parents Read Dreams I’ve Had About Them from 1998 and A System for Writing Thank-You Notes from 2001. Above on a wall is Goldberg’s nearly silent My Father Breathing Into a Mirror from 2005. (More about them later.)

Bert Rodriguez’s A Wall I Built With My Father (Western Bridge)

is almost impossible to see, as it is hiding in plain sight. It’s a

freestanding white wall with nothing on it. Rodriguez created it with

his dad to heal their rift and assert it. Builder Zac Young built the

WB version with his dad, also a builder, who came out of retirement for

this project at the request of his son.

Behind Rodriguez, Kerry Tribe’s two-channel, split-screen video, Here and Elsewhere

is playing in a separate, sound-suppressing gallery. Tribe adapted

questions from Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Mieville’s

FRANCE/TOUR/DETOUR/DEUS/ENFANTS from 1977, casting film theorist Peter

Wollen as the off-screen interviewer and his daughter Audrey as his

bright, trying-hard-to-please subject.

When Wollen asks her what an image tells her, she says:

When Wollen asks her what an image tells her, she says:

It depends

on what you want me to … what you’re expecting.

I

winced, but who could deny that such discussions with her

philosophically-inclined father about time, light and memory open the

world for this child? When he asks who she is in the video, herself or

herself playing herself, her eyes gleam because she has a good answer.

“Both,” she says. “I’m doing both.”

Jessica Jackson Hutchins‘ Sun Valley Road Trip

from 2006-2007 is a different approach to bringing up baby. Hutchins’

two-year-old is not in her car seat. Undoubtedly, she put her small

foot down at the prospect of being restrained during such a long trip.

Hutchins captures a parent’s fascination, tedium, love and fear.

Zeyl’s

massive staircase, steeper than scale, reflects the familiar through a

toddler’s eyes, when the ordinary act of climbing the stairs is an

obstacle. Upstairs is Guy Ben-Ner‘s video Stealing Beauty.

It’s Marx Brothers Marxism, played by Ben-Ner and his two

children.There is also a wall of portraits of the children of Western

Bridge founders Bill and Ruth True, chiefly by Alice Wheeler (joyously free-form) and Colleen Chartier (pristine).

Back to Goldberg.

Video

1: As an adult child, he’s in charge and his parents compliant. Because

he wanted them to be serious while reading his dreams about them, his

mother struggles to hide a smile behind her poker face. Neither looks

at him for fear of ruining his art.

Video

Video

2: After his mother’s death, Goldberg helped his father, an engineer,

write a list of sentences that could be recycled through many thank-you

notes, as appropriate.The order of the project highlights a chaos of

loss.

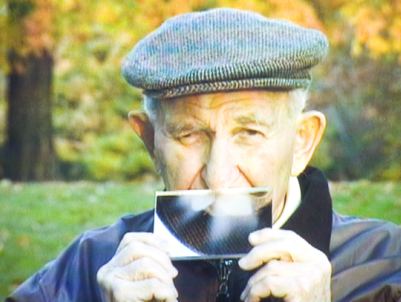

Video 3: My Father Breathing Into a Mirror, a one-minute loop, completes the the cycle. In it, his father stands in a park on a brisk fall day and lets his son film the

small hills of fog his breath makes, his eyes never leaving the face of

his son holding a camera.

Breath is proof that the father lives, at

least for the duration of the video. The proof that matters is the

evidence of love. Goldberg conceived this piece after his mother’s

death and while his father, now dead, was failing. By participating,

his father reassured him. The video is the father wordlessly proving

that he’ll be there, even after he’s gone, in every breath his son

takes. Look, he’s saying. It’s easy, and it will never end.

Leave a Reply