First sad sack: We were raised in a corridor. We longed for a room.

Second sad sack: We longed for a corridor. We were raised on

a road.

Not since 17th-century Chinese painters focused on the fluid connectives between forms has empty space been as riveting a subject as it is now.

Rachel Whiteread is crucial in this context, but by the time she began to explore the space between legs of a chair, for instance, Bruce Nauman had already been there and gone. (The peerless Peter Schjeldahl described their relationship as Nauman’s Chuck Berry to Whiteread’s Beatles.)

In Seattle, Leo Saul Berk has his own version of the theme: empty space as landscape narrative. In his exhibit at Lawrimore Project, Deep, Dark, he maps the volumes of famous undergrounds, including the hole in which Saddam Hussein unsuccessfully sought refuge after the U.S. invasion of his country on trumped-up charges.

Spider Hole, 2009 Fiberglass, foam, resin and glass. 6 x 4 x 10 feet.

Berk gives volume to the photos, schematics and renderings of the box-cave trailing a partial tunnel that the U.S. military released to the media. Hanging from the ceiling and painted yellow to mirror U.S. ridicule of the sole occupant, Spider Hole is a positive projection asserting itself with a phallus, snake, tongue and weapon.

Berk gives volume to the photos, schematics and renderings of the box-cave trailing a partial tunnel that the U.S. military released to the media. Hanging from the ceiling and painted yellow to mirror U.S. ridicule of the sole occupant, Spider Hole is a positive projection asserting itself with a phallus, snake, tongue and weapon.

Who’s weapon? Not the butcher of Baghdad’s. Glass beads ordinarily used for roadway strips give the piece its disco glitter.

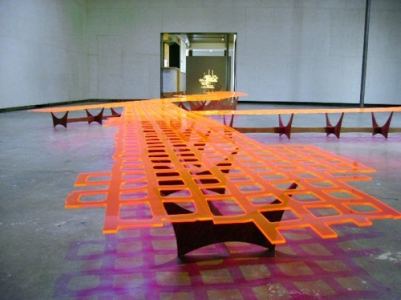

Quecreek Mine, 2009 Acrylic and walnut. 30 x 2.5 x 22 feet.

The

Quecreek Mine collapse came after 9/11 and during the build up to the

Iraq War. Nine men trapped 240-feet underground managed to run to the

highest point of their three-to-five feet high coffin and find a bubble

of air as water roofed the structure.

Thanks to the miners

themselves and the rescue crew of engineers who did everything right,

everybody got out alive. There was only one side to be on during the

78-hour ordeal. When that side won, it was a rare piece of good news

for a rattled country. For a moment or two, everybody ignored the

inherently flawed nature of an industry tearing up the earth and using

humans as disposal parts.

Orange acrylic dips and rises as it tracks a layout through an echoing grid of purple shadows. Cracked in spots and porous throughout, the piece is tapped out, with empty squares where earth used to be. As Chinese landscapes move from earth to sky to water, Quecreek Mine also metaphor for the river that ran through it.

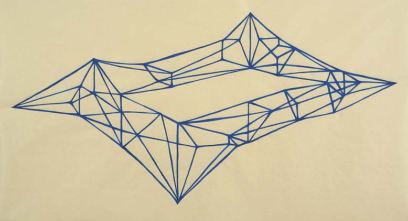

Dark House, 2008 Detail of a multi-panel drawing

Dark House

Dark House

is a computer-generated drawing made with a jellyroll pen beloved by

teenage girls for its shine. It tracks the interior a Mayan cave, Naj

Tunichat, long closed to the public. A couple of years ago, because

Berk’s brother was getting married and hiking through the Guatemalan

jungles as a last hurrah for his single life, he bribed the guard to

let them enter.

Down they went. Berk followed his brother into

deep time and re-emerged with an image in mind of a fragile space

battered by duration.

Tora Bora, 2009 Wood. 60 x 60 x 40 inches.

proved fanciful. Their unreality parallels the battle there, during

which Afghan soldiers allowed the mass murderer to slip away after U.S.

forces had routed the Taliban and al-Qaeda defenses.

Berk

stuck to the original model. He carved its dimensions in wood, leaving

room for the hydro-electric dam that wasn’t there, giving form to a

James Bond, bad guy fantasy.

Deep, Dark

delves into the psychology of the underground man. Real or not, all are

spaces envisioned to hold him. Working on this show, Berk said he was

thinking about the work of Victoria Haven, another magician of the earth who renders solids into fluids and back to elusive solids again.

Haven, IF ALL IN ALL IS TRUE, 2009 Watercolor/paper 32.25 x 57 inches, image via Greg Kucera Gallery.

Lawrimore Project has never looked this good.

Leo staggers me. This show is sick, sick good.