Consider your stinking carcass. What if, in addition to the options of burial and burning, you could condense yourself into colored air, hover for a moment to amaze the multitude and disappear?

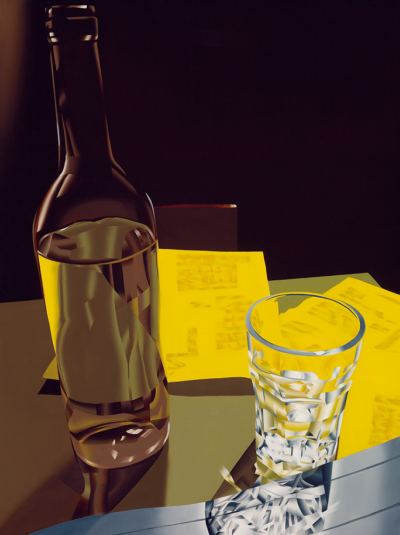

The subject of Joseph Park’s Absinthe is, most obviously, a homage to Degas’ Absinthe Drinker and to Picasso’s Arlequin, but the subject of references is not his root subject. Park deals with the world that paintings make: how they can be constructed like crystallized

The subject of Joseph Park’s Absinthe is, most obviously, a homage to Degas’ Absinthe Drinker and to Picasso’s Arlequin, but the subject of references is not his root subject. Park deals with the world that paintings make: how they can be constructed like crystallized

growth clumps or shards to accumulate over an image.

With his immaculate surfaces, tightly controlled tonal range, fluid brushwork and ability to animate empty space, Park brings an

embalmer’s gifts to his cultural critiques. The first impression he makes is of vitality. The second is vitality strangled.

It’s that sinister backbeat coupled with an undertow of bleak beauty that moves us in the end.

Park’s facility can be off-putting to those committed to more rugged representations. About Park’s current exhibit at the Portland Art Museum, Chas Bowie wrote:

The critical hazard of making dazzling artworks, of course, is that you

fall so in love with your refined flourishes that you fail to notice

that you’ve drifted into the unseemly realm of razzle-dazzle. (more)

Why is facility an unseemly realm? Fragonard put up with this sort of thing towards the end of his career. But who today looks at The Swing and sees only a razzle-dazzle version of an upper-class, covet dalliance? No, it’s the slipper crafted on earth that floats in the air, pink rising above the larger pink of a desirable women to claim a place amid the artist’s lights and shades.

Art requires the facility it requires, different in every case.

Waiting for Claude: (The Claude to whom the title refers is worth the wait.)

Still Life: Loaded

Still Life: Loaded

complexities of family life. Those are his shoes inside his

grandmother’s sealed in a glass table top, the past always present in

the mind of a maker, maker’s tools above them.

p leonilla:

p leonilla:

The touchstone is a 1843 portrait by

Franz Winterhalter. The sky is gift wrap, as if she were the Candy Kiss

at its center wrapped in a ribbon. She fingers her necklace, a tribute

to what the hand creates, every inch of space.

Machinist:

Machinist:

Again, what is made, the surface of a cluttered world orchestrated into

a perfect sheen, a memory of trying to build go-carts as a child, via Thomas Ruff’s photos of dark and meticulous machines.

Still Life:

Still Life:

Visible brush stroke on the left with what looks like a roll of damp toilet paper,

disappearing into the dark polish on the right with a gesture, through

a child’s puzzle, to his earlier work. Note that the puzzle is incomplete.

Through Nov. 15.Curated by Bruce Gunether, PAM’s chief curator; proposed by Jennifer Gately, former PAM curator of Northwest art.

Through Nov. 15.Curated by Bruce Gunether, PAM’s chief curator; proposed by Jennifer Gately, former PAM curator of Northwest art.

Leave a Reply