Note: Seattle artist Matthew Offenbacher publishes a quarterly newsletter titled, La Especial Norte, now at issue #4, featuring essays by Seattle artists and reprinted essays from artists from elsewhere. It’s free but not online. Offenbacher likes print, although by the next issue, he promises to have an article archive on the Web.

His essay titled Green Gothic is in the current issue, reprinted by permission. Emily Carr’s and Gretchen Bennett’s images from the article. Other images (and the links) added by me.

I saw Twilight the other day, the teen vampire movie set in Forks. Local vampire Edward falls for the new kid at school, a pretty transplant from Arizona with the unlikely name Bella Swan. Edward is an unusually urbane vampire. He lives with his family in a Northwest modernist dream house in the woods. He drinks only non-human blood. Deer, mostly. He is sort of like a vegetarian in the vampire world. Oregon scenery (standing in for the Peninsula) co-stars. Whenever the camera can tear itself away from the lovers’ tortured faces, the screen is lit by a million shades of green.

(Glenn Rudolph, Via)

In Gothic stories landscape is destiny. A character’s inner life is reflected by their surroundings. In one scene, the young lovers go on a field trip with their biology class to a greenhouse and gaze into a wormy bin of compost. This is an everyday lesson in the damp, decaying, riotously fecund Northwest: the decomposition of dead things is what allows new life to grow. Why is Edward and Bella’s romance accompanied by the lush Northwest landscape? Maybe it is because Edward is a different sort of monster. Vampires are undead, a death which feeds on life in order to obtain a semblance of life, an anti-ecology, a reversal of the nitrogen cycle. Edward struggles to reconcile this existential horribleness with his sense of morality. Bella, meanwhile, is attracted to his dark, freakish, supernatural strangeness. The dilemmas Edward and Bella face echo those of much of the art which engages the history and ecology of the Northwest landscape.

In Gothic stories landscape is destiny. A character’s inner life is reflected by their surroundings. In one scene, the young lovers go on a field trip with their biology class to a greenhouse and gaze into a wormy bin of compost. This is an everyday lesson in the damp, decaying, riotously fecund Northwest: the decomposition of dead things is what allows new life to grow. Why is Edward and Bella’s romance accompanied by the lush Northwest landscape? Maybe it is because Edward is a different sort of monster. Vampires are undead, a death which feeds on life in order to obtain a semblance of life, an anti-ecology, a reversal of the nitrogen cycle. Edward struggles to reconcile this existential horribleness with his sense of morality. Bella, meanwhile, is attracted to his dark, freakish, supernatural strangeness. The dilemmas Edward and Bella face echo those of much of the art which engages the history and ecology of the Northwest landscape.

What do you do if you love a monster? What if you are a monster, an ethical and moral creature who happens to be an abomination?

(Glenn Rudolph, Via)

Perhaps the most obvious example is Mark Dion’s Neukom Vivarium, a massive decomposing hemlock log parked inside a green-glass building at the Olympic Sculpture Park.

Perhaps the most obvious example is Mark Dion’s Neukom Vivarium, a massive decomposing hemlock log parked inside a green-glass building at the Olympic Sculpture Park.

In an interview for PBS, Dion had this to say about it:

In an interview for PBS, Dion had this to say about it:

In some ways, this project is an abomination. We’re taking…an ecosystem–a dead tree, but a living system–and we are re-contextualizing it….We’re pumping it up with a life-support system. So this piece is in some way perverse. It shows that, despite all of our technology and money, when we destroy a natural system it’s virtually impossible to get it back.

The Vivarium log is like the Beast from Beauty and the Beast, imprisoned in a magic castle, waiting for Belle to fall in love with him. How do you deal with an abomination? You imprison it (and it will become an abomination partly as a result of the imprisonment) and wait for love to redeem it.

If the Vivarium applies a wishful strain of romantic thought to the problems caused by the destruction of natural systems–a monster in a glass cage to prick our consciences–Gas Works Park, the park designed by Richard Haag for the north end of Lake Union, is more pragmatic.

This comment, from the initial Environmental Impact Statement, gives a sense of the challenges Haag faced:

In the course of industrial, utility, mining, and forestry

works [the land for the park] has been degraded, soiled, polluted,

fouled, defaced, made odious, besmirched, and clogged with filth.

Gas Works’ most striking features–the towering tanks, pipes, and walls

left from the old gasification plant –are like the decomposing

medieval churches John Ruskin cultivated an appreciation for in the

mid-1800s. By preserving and studying these ruins he hoped to find a

way to mediate some of the dehumanizing effects of the industrial

revolution. The ruins at Gas Works Park evoke a powerful nostalgia

for–and mark the passing of–a not-so-distant time, when the enormous

resources of our natural environment were harnessed to build a great

civilization.

That this harnessing did not come without great cost was address by

the other part of Haag’s plan, which called for “cleaning and greening”

the site. This involved removing toxic sludge, mixing it with filler

and stockpiling it in a huge burial mound; introducing microorganisms

to digest organic waste, and plants to leech heavy metals and minerals

out of the topsoil. This was one of the earliest attempts at

bioremediation, using the natural agents of decay and re-growth to set

an ecological cycle spinning in a healthy direction.

(Matthew Offenbacher, Via)

That this sort of remediation is imperfect is something I think Haag acknowledged in another great work, the Bloedel Reserve on Bainbridge Island.

That this sort of remediation is imperfect is something I think Haag acknowledged in another great work, the Bloedel Reserve on Bainbridge Island.

Bloedel is the site of an old logged second-growth forest, transformed

by a timber industry family over the course of fifty plus years into a

series of bucolic gardens. Among Haag’s contributions is a moss garden,

where damp, lush, electric green mosses and lichens are set against

massive, blackened, upturned tree stumps. You can see on the stumps

evidence of the cuttings and lashings afflicted by long-ago logging

machines. The mosses and the logs are delicately balanced between

preservation and remediation.

Bloedel’ s mosses glacially devouring the evidence of

clear-cutting, the tar which still occasionally bubbles up through the

green lawn of the burial mound at Gas Works –these are clearly

monstrous sites–but there is this sense that they are monsters

struggling with their monstrosity. Haag wants to find a cure for the

Beast’s condition, but he is also suggesting we love him for his

betweenness, his twilight struggle.

The symbolic and practical uses of decay, its productive and

potentially redemptive force, seems to be on quite a few artists’ minds

these days. A few examples: Eli Hansen and Joey Piecuch’s show

earlier this year at the Helm in Tacoma featured a variety of

hand-blown glass stills, spiked with native plants and fungi, poisons,

and stuff taken from famously disturbed Northwest sites (“soil from

Lewis and Clark’s Cape Disappointment camp site, concrete from Boeing

plant in Everett”). This was an attempt at redemption by one of the

oldest forms of useful rot: fermentation. Corin Hewitt’s current show

at the Seattle Art Museum also hinges on the redemptive power of

vegetative decay, in this case in an attempt to remedy some of the

toxic aspects of the culture of photography, art production and

circulation. John Grade has

been working in this territory, subjecting his sculptures to cycles of

exhibition, decomposition in natural areas, and then exhibition again.

(Grade – detail)

This interest in decay, industrial sites, and redemption is not a recent development. A painting by Emily Carr from 1935, Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky, shows three crazily spindly pine trees rising over a clear-cut.

They are almost all attenuated trunk, just a little cap of dark green

vegetation at the top. The composition echoes traditional pictures of

Golgotha, with Jesus hanging from one of three crosses. The closest

tree almost spans the entire canvas’ height, just left of the center;

the other two recede in sharp perspective towards distant, glowing blue

hills. The luminous rain-heavy sky frames the closest tree with the

kind of radial-light-projecting-through-the-clouds bit that, growing up

in Oregon, we used to call the ‘god-light.’ The ravages of heavy

industry have passed, people and machines have hauled off everything

useful. Left behind: the shunned, the freakish, the not worth taking. Scorned as Timber

is not a picture of abomination in confinement, or abomination in

remediation–it is a picture of survival because of abomination. This

is a radical move. It says, in effect, forget Belle. This beast does

not need to be redeemed.

(Allison Schulnik, Via)

I think it is significant that this proto-punk gesture by Carr does not

depict a single survivor, but a small group. Survival as a freak

requires community, or at least others nearby. This is something Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, Guy Anderson,

et al. understood. They were bohemians, esthetes, pacifists, and gay.

The gothic flavor of their work is an expression of the great

alienation they felt in Skagit county in the 1940s and 50s.

That many of them, like Carr, looked to the natural environment to find

a way to talk about their situation should not be surprising; this

commingling of insides and outsides, of psychic and physical

terrain–and, especially, of industrial and personal trauma–has been a

consistent feature of art produced in our region. Graves 1944 gouache Bird Sensing the Essential Insanities

shows a flattened little owl in a submissive position, crouching on

what might be a boulder, looking like it was just stepped on.

A skeletal Wounded Gull from the next year is beginning to

decompose on a tar-like shore. These birds have suffered grievous

threats and injuries, but they survive. Eventually, in paintings like

1969’s Bird Experiencing Light, where a very odd-looking bird is awash in a glorious mass of yellow, purple, magenta–they triumph.

Which lands me at the work which got me thinking about these things in the first place: Gretchen Bennett‘s show Hello

last year at Howard House. Gretchen has consistently investigated

notions of place, psychology, and the Northwest landscape. This is why

some people were startled by these nine colored-pencil drawings based

on video stills related to the band Nirvana and, especially, Kurt

Cobain. Most of the stills were from old music video and concert

footage posted on YouTube. A few were captured from the movie Last Days,

Gus Van Sant’s fictionalization of the end of Cobain’s life. Gretchen

made the drawings by projecting the images onto paper and working

directly over them, trying to capture the luminous effects and odd

visual distortions of the found video.

The drawings from Hello pull together many of the strands I’ve

been talking about here, in an exceedingly delicate and direct way.

What is the ethical approach to sites of industrial exploitation

(imprisonment? remediation?). How might decay and rot be used as agents

of redemption? How can you learn to love an abomination? How do you

survive being an abomination yourself? Gretchen’s innovation was to

reverse the usual direction of landscape metaphor–the direction which

Ruskin once called “the pathetic fallacy”–which projects the personal

out onto the landscape, personifying the natural world. Instead, the

Hello drawings project the landscape back onto the personal. They

portray Cobain as a landscape, a landscape we all inhabit.

In the drawing Have a Hangover (above), Gretchen chose

a moment where the camera was directed at Cobain standing directly in

front of a stage light. The top half of the drawing is blasted with

light; body, guitar and microphone are rendered by shivering halos, and

distorted by concentric lens flares. The way Gretchen draws Cobain

here, and in many of the drawings, has obvious parallels to Grave’s

birds and Carr’s trees–the spectral god-light is in full glorious

evidence. Also, like in Carr’s painting, the Hello drawings depict a

site of industrial exploitation (a music video is, after all, a

commercial for a record company). There is a similar, peculiar

combination of violence and hushed stillness. This is the moment after

the violence is over. We are witnessing the survivors, triumphant and

transcendent.

There is a tenderness to the drawings’ fidelity to layers of

distortion caused by cameras, and then the further decay caused by

YouTube’s compression algorithms. This tenderness is like Haag’s at Gas

Works and Bloedel . Gretchen is involved in the remediation of a former

industrial site, searching for a remedy, a way to put decay and

decomposition to work. The Hello drawings manage to simultaneously show

the Cobain who was different, and scorned, and made art from that

experience, and then, suddenly, improbably, with great force, became a

very valuable industrial site, and then–in the end–and this is why

there are images from Last Days –the ultimately devastating

toll this exploitation took. In a typically subtle move, one which sent

tingles up my spine when I realized it, the drawings were shown without

glass in their frames. This act of opening up, of making vulnerable, is

as clear a sign as any of Gretchen’s desire to remediate the many

layers of mediation between us and these images–to create a productive

state of decay, to understand redemption as continued and ongoing

struggle, and to recognize Cobain as the monster he was, as the

monsters we are too.

(Matthew Day Jackson, Via)

Offenbacher ‘s Notes:

Offenbacher ‘s Notes:

My editor told me I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the archetypal good vampires Angel and Spike from the TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

For anyone with an interest in the theme of the redemptive power of

love on vampires, these characters–especially Spike–are infinitely

more complex and interesting creations than Twilight ‘s Edward. The landscape they inhabit, however, is much more typically Gothic.

The interview snippet with Dion is from a 2007 episode of the PBS television series Art21 focusing on art and ecology.

Surprisingly little has been written about Richard Haag’s work. I’ve

been influenced by an excellent essay Elizabeth Meyer wrote for a

monograph edited by William Saunders: Richard Haag: Bloedel Reserve and Gas Work Park

(Princeton Architectural press, 1998). The public comment from the Gas

Works EIS was written by Benella Caminiti, as cited by Meyer.

For more on Ruskin’s idea of the Gothic, see chapter VI The Nature of Gothic from The Stones of Venice (1851-53).

The terms he uses to describe Gothic architecture are: savageness,

changefulness, naturalism, grotesqueness, rigidity, and redundance.

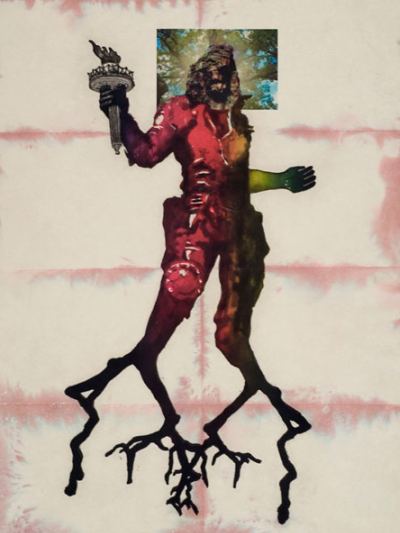

For more on the gayness of the Northwest School, see Matthew Kangas’ Prometheus Ascending: Homoerotic Imagery of the Northwest School, from his 2005 collection of essays Epicenter .

That’s it. Thank you for reading all the way to the very end.

Leave a Reply