Everybody’s got something to hide ‘cept for me and my monkey.

– John Lennon

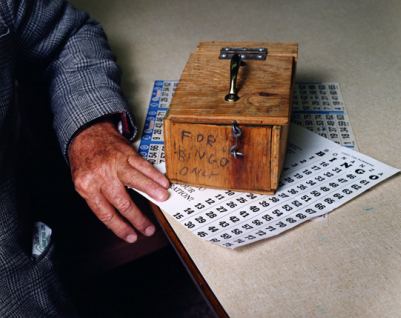

Andrew Miksys:

Miksys won his first bingo game at 11, collecting $280. In high school he delivered a newspaper his father published, Bingo

Today, to veterans halls, fraternal associations, churches and sports

clubs in Seattle.

He knows the people he photographs in bingo halls, most of whom are dead and don’t know it. The routine of the game keeps them in a pretense of motion. They

stare are their cards the way the empty eye sockets of skeletons stare

into eternity.

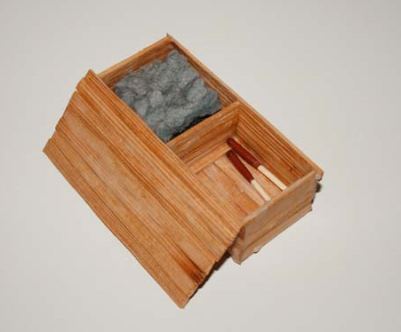

Below, their stash.

Politicians infantilize the audience by reducing its members to first

names and jobs, as if everybody is a waiter in a cheap restaurant,

always on duty.

(Joe the Plumber.) Artists do the reverse. Instead of gassing up a stereotype till it

rises like a parade float, they use absurdist intensity to bring it to ground where it can be examined, ridiculed, celebrated and/or fractured into

the particular.

Take Matt Browning, who explained himself in his debut exhibit at Seattle’s Crawl Space late last year:

Men typically engage in bizarre competitions and intrepid

behavior during their lives as a means of bolstering machismo and

camaraderie. Instituting male pedagogy, identity and peer acceptance in

suburban America can, for example, take the form of climbing the

tallest tree as a child, asserting athletic prowess in adolescence, and

winning reckless drinking competitions in early adulthood. My work

illustrates the simultaneous presence of lunacy and beauty in these

types of testosterone-laden behaviors.

He digs to the root of male desire and

finds it wrapped in baseball, beer, pot, skate boarding and the blunt end of taking things

apart:

Leave no trace, review here.

Liz Magor:

Liz Magor:

When she was a child, she liked to slip into a forest near her

home in search of a kid-size weasel hole. She thought if she lived

there with a dog and a bag of potatoes, the silence of the natural

world would replace the ruckus in her head. Her work is about the folly of aspiring to be in a hole, and the cultures that become one.

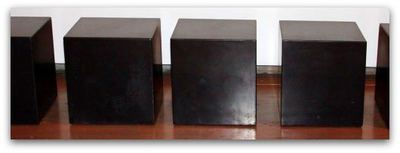

Inside a series of small black boxes Daws sealed a variety of drugs, from crack cocaine and crystal meth to ecstasy, heroin and LSD.

Partially, they are a tribute to Robert Morris’ box sculpture from 1961, Sculpture With the Sound of Its Own Making, as well as Charles Ray’s Ink Box from 1986, which wasn’t a box but a vat of black ink. Those who touched its surface expecting something smooth and hard came away with a record of their infraction on their fingers.

Daws’ infraction is an inside job. Who is in possession of the drugs, and who is the pusher when no one can lay hands on the substances in question (assuming they’re really there) without destroying the art?

Felony Sculpture

Fritz thinks inside the box, where she finds fragments of your inner life. When you were otherwise engaged, what was private became public and subject to experiment. Her merger of science and art involves video, mechanical contraptions, cast-polyester molds and a tendency to surround images with thick slabs of silence.

Like Larry Bell, her boxes are all about light, but unlike his spare volumes that trap light on their surfaces through a variety of coated films, her light needs the light in the larger room shut off to be seen at all.

In the dark, when her fuzzy and uncertain pulses are the only illumination, they slide around you and take you in. In Section 4, a cat’s shadow appears inside a box, lit by the milky glow of her video screen. The cat hesitates at the locked door and bows its head.

Section 4

Leave a Reply