Robert Colescott (1925-2009) was a trim, soft-spoken man with a halo of white hair on his handsome head. His manners were courtly, his eyes appraising. He could walk into a room and take everything in. He knew the dirt and failed to hold a grudge.

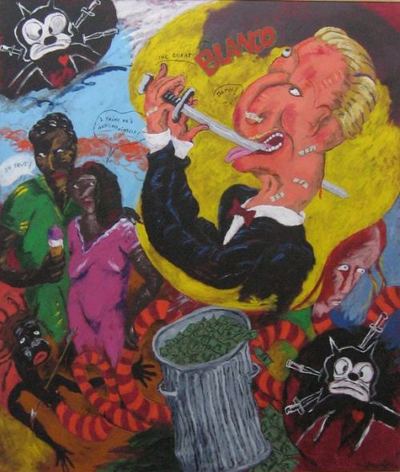

Ode to Joy (European Anthem),1997

(Via NYT)

As a young painter, he lived in Seattle and found it comfortable but provincial:

As a young painter, he lived in Seattle and found it comfortable but provincial:

Influences came in slowly but didn’t mature and go back out again.

He had just graduated with an MFA from UC Berkeley and had spent a year in Paris studying with Fernand Leger.

Married, Colescott had a young child and another on the way.

While white graduate students at the time easily secured employment at colleges and universities, nothing turned up for him.

I was in a sense more qualified than my peers. None of them had studied with Leger. Why wasn’t I hired? There’s the obvious reason, but I wouldn’t want to guess.

After coming up empty on the college level, he papered the country’s high schools and junior highs with teaching applications. A junior high in West Seattle finally called. Eventually, he taught there and in a junior high on Queen Anne.

I was a mail-order bride, shipped to Seattle.

Although he felt isolated and could never get used to the damp weather, he made a number of important friendships here, especially with the late painter William Ivey.

I hate to talk about him in the past tense. Bill and I sat up nights thrashing out issues of representation. He may well have been as much of an influence on me as anybody.

When Colescott left, it was to teach at Portland State University in Oregon for nine years.

He was probably happiest in Arizona on his own five acres of desert, the proud father of five children.

I hope when they think about me, they think about what I’ve been able to do against certain kinds of odds.

For most of his career, being black in the art world was like riding a bicycle in a swimming pool. No matter how good the swimmer, it’s tough doing laps on a bike.

When the issue came up at all, curators, dealers, collectors and critics could be counted on to affirm their high-minded commitment to quality in art, regardless of the race or sex of the maker.

And yet in overwhelming numbers, the artists in the forefront continued to be white males. White females came next and people of color far in the rear.

Even though white is no longer always right in art circles, Colescott made his reputation before that change.

What’s more, he achieved a position in New York during a time when being from the West Coast was almost as bad as being black.

I had the idea of the moment. I worked it out in Seattle and it took me places.

That idea was straightforward.

He combined expressionist brush strokes with a narrative content (and

love of comics) that pushed people out of comfort zones. With fluid but

dizzying shift scales, he packed his picture plane and turned a search

beam on the unmentionable.

In 1970, when he opened his first show in

New York in a now-defunct space on West Broadway called the Razor Gallery, he drew crowds.

The minimalist aesthetic held sway, but people were looking for something else.

Philip Guston

provided it in 1968, moving from Abstract Expressionism to drawings of

fat guys smoking cigars with KKK hoods over their heads. Hilton Kramer

called him a “mandarin imitating a stumblebum.”

Instead, Guston was changing history, providing a path for a generation

of painters, and Colescott was with him.

But Colescott was more of a satirist than Guston.

Even people who loved Guston’s second wind had a hard time with Colescott’s first.

He made his mark by reveling in stereotypes. His canvases are

full of dizzy blondes and the black males who salivate over them:

frenzies of jungle fever. Kara Walker wouldn’t be possible without him, nor would generations of artists who are not afraid to be both funny and offensive.

Colescott painted sore spots with humor, rancor and compassion.

In The Sword Swallower,

a white man holds a slippery center stage. He’s a tornado in human

shape tearing holes in his throat.

Behind him a black couple half his size appraise him sympathetically.

“I think he’s hurting himself,” the woman says, her words rendered in

stringy letters encased in a comics-style bubble. “It’s true,” her

man replies. A fast, fleet-footed painting, it’s full of hot lights and

sheltering shades.

Ridicule is a way to break things up. Think Dada. It’s a tool, a weapon and a basis for structure.

His central interest was the shifting relationship

between abstract and narrative elements, which he said he picked up

from Leger.

Like any good communist, Leger wanted

to share what he knew. He thought abstract art didn’t communicate with

the people. He had a beautifully monumental simplicity about his

figures, and he plugged the necessity of a narrative.

Colescott began as an abstract artist, and his later work was increasing abstract.

Art

is a spiral. If you keep painting long enough you come back to where

you started, but not quite. You bring the baggage of all you’ve

learned. As long as I’m willing to let something new happen, the work

continues to develop. If not, it’s a disaster.

About representing the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1997, one of contemporary art’s genuine pinnacles:

I’m

working my way through it. Like the bumper sticker says, `I’d rather be

surfing.’ It’s an honor, a privilege and a pain in the ass.

(Quotes from a 1997 interview in the now demised Seattle PI)

Cue the chorus – obits:

Richard Lacayo (Looking Around) here.

Roberta Smith (NYT) here.

Suzanne Muchnic (LA Times) here.

Richard Nielsen (Arizona Republic) here.

Charlie Finch (Artnet) here.

Emily Langer (Washington Post) here.

DK Row (Oregonian) here. (Too brief, but promising more.)

Regina, thank you for this. I just recently got into Colescott because the Henry has his Cruise to Southern Waters (1988) on view. I love the vivid colors and loose brushwork. But what I love most about the painting is that the peachy-toned white people have shades of brown and black in their skin, and the chocolatey-toned black people have shades of peach in their skin.

Check this out @ 3:25 Thelma Golden on TED