At the press preview for the Seattle Art Museum’s small but choice Wyeth exhibit, Remembrance, exhibit curator Patricia Junker said Wyeth was the figure whom the international crew of artists featured in Michael Darling’s Target Practice: Painting Under Attack (1949-78) had in mind.

Both exhibits open tomorrow. (Target Practice reviews to follow.)

Wyeth’s admirers try to insinuate him into the thick of things. For the artists in Target Practice, however, he wasn’t on the firing range. Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning. Andrew Wyeth? His name did not come up.

Wyeth backed himself into a corner of a particular place rooted in land and family and painted his fear of the world. With a desperate and dry exactitude, he documented every inch of what mattered to him. He aimed for sentimentality but didn’t get there.

Wyeth backed himself into a corner of a particular place rooted in land and family and painted his fear of the world. With a desperate and dry exactitude, he documented every inch of what mattered to him. He aimed for sentimentality but didn’t get there.

His idea of the beautiful is dead-on-arrival, but his depiction is the equivalent of Miss Havisham preserving her cake.

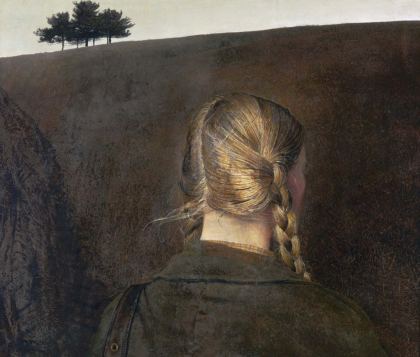

Take Farm Road, above. (1979, Tempera on masonite, 21 inches high by 25 1/4 inches wide. Private collection.) Rembrandt-light shines on the greasy hair of his model, gray and brown at its roots and brass in its braids. Is the farm road in the title the rigid path of her hair? There is no other.

The rusted iron ground that rises in front of her blocks her progress. She’s right where he wants her, under his surveil, every hair on her head counted. Above, where she isn’t looking, the flat light of another dull day rises against a horizon line broken by a cluster of trees.

Wyeth is the American version of Edvard Munch, literal where Munch is flowing but tapping into the same emotional territory. Wyeth’s scream is that there is no scream. He’s the painter of a vast suppression, what it took for him to pass for normal in the countryside.

I dunno.

Look at his portrait of Anna Christina (of “World” fame) – gnarly and present. And the Weatherside, which is a house-as-portrait of her.

I like your parallel to Munch – very on target.

So you don’t like Wyeth!

You write that his admirers “try to insinuate him into the thick of things.” Indeed we do. You may have been thinking of Patricia Junker, curator of the current Wyeth exhibition you mention. Well of course she thinks that he was the painter (or at least one of them) whom the avant-gardists featured in “Target Practice” had in mind. She hadn’t yet seen the show and may have been relying on curator Michael Darling’s observation that for them, “painting had become a trap, and they devised numerous ways to escape the conventions and break the traditions that had been passed down to them over hundreds of years.” Wyeth’s painting is largely steeped in those conventions and traditions, whereas work by those Darling cites—Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol—is not.

You complain that Wyeth “backed himself into a corner of a particular place rooted in land and family.” Put another way, he painted what he knew best—friends, family, and neighbors, and the land upon which he and they lived. Lots of artists, from the Lascaux cave painters to Vermeer, Millet, and Mario Andres Robinson have “backed [themselves] into corner[s]” rooted in the familiar. Nothing wrong with that. Some of those corners are pretty rich.

Wyeth painted “his fear of the world,” you say. That’s a pretty strong assertion, suggesting that fear permeates all or most of his paintings. Not so. Not even some. Where’s the fear in ‘Marriage’ (1993), or ‘Meter Box’ (1983), or ‘That Gentleman’ (1960), for example? (Readers can find these and other Wyeth paintings by searching at Google Images.)

You say that Wyeth “documented every inch of what mattered to him” “with a desperate and dry exactitude.” Another assertion you apply to most if not all of his work. Where is the “desperation” in the paintings I cite above, or in any others you might name.

In ‘Farm Road’ (1979), which you illustrate, you see no road, though there seems to be one on the left side. You see the ground as “block[ing] her progress.” I don’t. She appears to be lost in thought and is just facing in its direction. “She’s right where he wants her, under his surveil. . . .” Isn’t that where the model should have been if he wanted to paint that painting—“under his surveil”? You make it sound so ominous! Another dull day? Dull? Not to me! And how do you know the days before that one were not sunny? You don’t.

Wyeth is Edvard Munch? Munch?!

Louis Torres, Co-Editor, Aristos (An Online Review of the Arts)

From what I understood of Andrey Wyeth was his interest in our fear of being along with ourselves as we don’t often find ourselves in that situation any longer.

Wyeth is a popular target. He was the consummate craftsmen and not a careerist in the form of a Jeff Koons or Mark Kostabi. I guess this makes him suspect.

I see Wyeth as a painter who loved to paint. A fact that was obvious in his pictures. He loved his craft in the same way Stevie Ray Vaughan, Monk, Louis Armstrong, Marcel Marceau, Picasso, Jack Nicholson, Judy Dench, etc, loved theirs. His commentary/politics/motivations, whatever it is that seems to be missing for most people’s liking were too subtle maybe.He was no ephemeralist. His pictures, whatever they may be, won’t change for convention or timing. The Helga series wasn’t quite a fabrication in porcelain of Michael Jackson and his chimp or basketballs in a fish tank, they inhabited a different space. I believe there’s room for all.

Maybe I’m crude myself, but I like his pictures.

I appreciate the discussion.