Mary Mattingly, from her series, Nomadographies, just closed at Robert Mann Gallery.

A lot of Mattingly’s images look like photo shoots for a fashion magazine, which is not the insult it used to be. Art worms its way into contexts that were once excluded, partly because they were once excluded. Plus, within the glamorously provocative, Mattingly has that extra element, a subtle and toned-down version of Matthew Barney. She goes for the myth but leaves pomp and circumstance to others.

A lot of Mattingly’s images look like photo shoots for a fashion magazine, which is not the insult it used to be. Art worms its way into contexts that were once excluded, partly because they were once excluded. Plus, within the glamorously provocative, Mattingly has that extra element, a subtle and toned-down version of Matthew Barney. She goes for the myth but leaves pomp and circumstance to others.

(Mattingly is a key contributor to the Waterpod Project, which opens Saturday in New York City. (More info from Artforum and the New York Times.)

Ford Gilbreath has no relationship to the world of runway glamor. In spite of the pellucid clarity of his photographs, he’s happy to work in the mud and is best known for hand-painted gelatin silver prints shot on the Duwamish in Seattle, a river long abused by heavy industry. It has the distinction of having one of the lowest oxygen counts in the country.

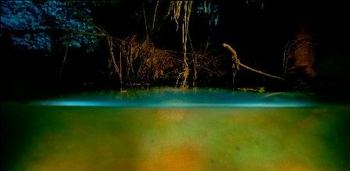

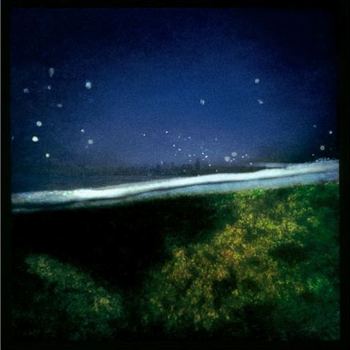

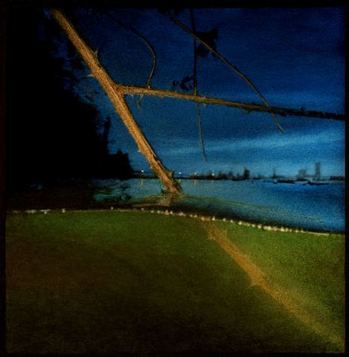

Gilbreath slogged through the river’s heavy-metal murk in chest-high waders, pushing his camera in front of him in a half-submerged aquarium. With flashes attached above and below the waterline to his Hasselblad camera, he produced a simultaneous look at two worlds: air and water divided by a fluid seam or horizon line. He added density to the stark, flattened effect achieved by the camera by painting the prints in layers with transparent oils.

Gilbreath slogged through the river’s heavy-metal murk in chest-high waders, pushing his camera in front of him in a half-submerged aquarium. With flashes attached above and below the waterline to his Hasselblad camera, he produced a simultaneous look at two worlds: air and water divided by a fluid seam or horizon line. He added density to the stark, flattened effect achieved by the camera by painting the prints in layers with transparent oils.

In his stagnant shallows, scum shines and greenish-brown depths

In his stagnant shallows, scum shines and greenish-brown depths

glow. He gives the drooping clumps of dead grass that hang over unnameable, watery masses scale and force beyond their size and importance. They are monuments in ruins, as graceful in their dying fall as the ruins of Greece and Rome.

Gilbreath on the moon here. His stereoscope images in the woods (here) are the only ones I’ve seen that don’t immediately ring the William Kentridge bell.

Gilbreath on the moon here. His stereoscope images in the woods (here) are the only ones I’ve seen that don’t immediately ring the William Kentridge bell.

Leave a Reply