An elderly man entering a hospital for tests is asked about his food

preferences. “I eat anything,” he responds, which turns out to be

untrue. He eats anything within the narrow range of what his wife

serves him.

The unexamined life may not be worth living, but it’s easier on the digestive tract.

Art

critics say they make aesthetic judgments about art, not about whatever

political content might serve as its subject matter. This stance is

easy for the typically leftist critic, because virtually all art with

overt political content comes from the left. It’s against the usual

negatives (war, racism, sexism, concentrated wealth, wasteful carbon

footprints) and in favor of the usual affirmatives (civil rights, human

rights, economic justice, social diversity and so forth.)

Happily I proceed, unchallenged, until considering the work of Charles Krafft. (Or, recently, nostalgic/romantic art

about Boy Scouts.) In both cases, I find that I am not as open-minded

as I think I am; that when it comes to political content, I am not

open-minded at all.

Krafft is having an accidental career survey at a resale gallery known as Seattle ARTresource, with a dozen paintings from the 1980s onward and 18 hand-painted ceramic plates from his Disasterware series.

Seeing

a fair sample of Krafft’s plates together for the first time in years,

I was struck by their secret narrative. They are an extended version of

the artist’s self-portrait, featuring the prickly ground of his

compulsion to offend.

To a Nazi-loving skinhead who told the artist he was his hero, Krafft replied,

I can’t imagine why. I’m making fun of you people.

More accurately, Krafft is making fun of everybody, including himself.

In 1992, when he had his last exhibit in a mainstream Seattle gallery (Davidson), Sam Davidson told me he was troubled by his own insistence that one of Krafft’s Disasterware plates not be in the show. After taking a look at the censored plate, I said, “Good call.”

I

use the word censored lightly. It isn’t censorship for a dealer to

decline to exhibit a particular artwork within a show featuring that

artist. It’s called curating. But curating to avoid giving offense

rightly troubled the dealer.

Created on the heels of the Rodney

King verdict and the Los Angeles riots, the piece struck me as

unbelievably racist. I didn’t write about it, being stumped as to what

to say and how to phrase it for placement in the PI. There was no way

the PI would have reproduced the image unless it were accompanied by a

ringing denunciation.

(Click images to enlarge.)

What

What

if instead of an African-American minstrel who plays the sax as LA

burns, the figure is a self-portrait, a slighted caricature of a

marginalized group – those who make art as the world goes to hell?

What

if the hostility is directed at himself? At the time, he was a Seattle

artist approaching middle-age with little hope of a wider audience;

passed over, ignored, full of rage, wicked glee and self-loathing. What

does the plate “mean” in this context?

What did it mean when Philip Guston began drawing himself

as a member of the KKK? However startling, it wasn’t controversial to

be sick of self, sick of America and in despair about the Viet Nam War.

Art. What is it good for? In order say “absolutely nothing,” Guston had to continue to make it.

During

a studio visit in the mid-1990s, Krafft put the plate below in my lap.

Immediate unease overcame me. He said he modeled the figure from a

photo featuring a Jewish victim of Nazi experiments. The man was not

not high. He’s dead.

I

I

told Krafft to get this thing off me, as I didn’t want to touch it.

Being Pop jaunty about mass murder didn’t work for me. It worked for

Mel Brooks, but he didn’t have images of actual victims on stage. Try

to hum Springtime for Hitler while looking at this plate.

Krafft

is the outsider son of an affluent and right-wing Seattle family. While

his father saluted the flag, Krafft took drugs and got kicked out of a

high school. In response, his dad was not above expressing parental

frustration with his fists. If Krafft is the model in the center, the

text makes sense.

AIRPLANE GLUE INTERESTED US MORE THAN AIRPLANES AND THAT DIDN’T GO OVER WELL WITH DAD.

Below, Krafft’s version of a commerative plate. His dad would have liked the original.

Krafft was midway in the journey of his life when he found himself

Krafft was midway in the journey of his life when he found himself

lost in a dark wood. He was painting in the mystic tradition of the

Northwest School after the school had closed. Mark Tobey was dead. Morris Graves was holed up in his Northern

California retreat. Guy Anderson was still in La Conner but

uninterested in reviving an art movement. He focused instead on the

celestial weather he was creating in his own work.

Krafft needed a movement, so he made one up.

Partly inspired by Seattle musicians (Nirvana, Pearl Jam,

Soundgarden) and partly by his friend, the L.A. auto pin-striper known

as Van Dutch, Krafft created his own version of Seattle Noir.

In 1991, he debuted his Disasterware, with famous scenes of

carnage painted in the kitsch style of tourist Dutch dinnerware. He

followed with his Metropolitan Mobile Museum truck show, titled, Charles Krafft, 1974-1994: The Happy Years.

He honored Morris Graves by founding the “Mystic Sons of Morris Graves, Lodge Number 93,” emphasizing the antic

side of the dreamy flower painter and delighting him in his old age. Looters steal back. Krafft wants it back, everything he tried to be among the bastards out there.

Looters steal back. Krafft wants it back, everything he tried to be among the bastards out there.

Not

in the current sampling of his work at Seattle ARTresouce is anything

from his Delftware weaponry, his mad-cow creamers, his human bone

china, Hitler teapot or Holland windmills with swastika-shaped blades.

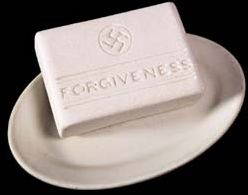

What

does this artist want? Maybe the key is a white ceramic bar of soap

with the word “forgiveness” impressed on its surface, along with a

swastika.

It’s a tribute to Slovenian artist Peter Mlakar, who said as he and

Krafft gazed out across a wrecked Olympics village in Sarajevo during a

cease-fire:

I love the smell of blood on the snow. If I could bottle

that scent, I’d create a new fragrance for the 21st century and call it

forgiveness.

Krafft says he has a few things in a show that opens in Seattle Thursday night, 7-9, at Porcelain Studio, 1020 1st Ave.

Leave a Reply