Doing the dog paddle, some people think they’re Esther Williams. Noah Grussgott lives in the gap between fact and optimistic fantasy. His chairs that are figures are made from material signs of distress (barricade tape, band aides, crumbling bits of brick wall and discarded foam core), but they occupy space with a jaunty elan. They are the best news they’ve ever heard.

Gathered together in Bleacher, they project a comic air of expectancy: Whatever is going to happen is going to be good.They are not troubled by their lack of forward momentum. Why travel when you’re already there?

Gathered together in Bleacher, they project a comic air of expectancy: Whatever is going to happen is going to be good.They are not troubled by their lack of forward momentum. Why travel when you’re already there?

Band aide chair:

Barricade tape chair: Although it’s an insufficient image, I love the cheap charm of his baby blue/girly pink foam core Frank Stella, on the wall below.

Although it’s an insufficient image, I love the cheap charm of his baby blue/girly pink foam core Frank Stella, on the wall below.

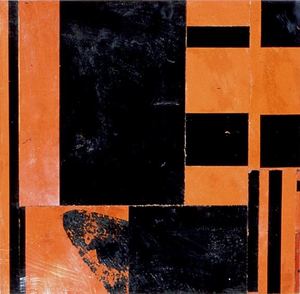

Robert Yoder’s battered geometries from the 1990s….

Robert Yoder’s battered geometries from the 1990s….

look positively regal next to Grussgott’s.

Although Yoder is almost always purely abstract, he has the weight to sound a serious depth. I’m not sure the same can be said of Grussgott.

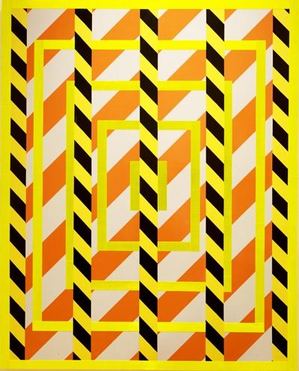

I used the swastika as a literal symbol, immediately recognizable as a

representation of hate. It’s both in a vulnerable/boxed in position as

well as at the center of the image. The intention was to simultaneously

discuss the ways in which symbols are sensitized and how overtime, even

a swastika can become a cliche.

But swastikas are not cliches. John Updike once wrote that what interests Saul Bellow does not appear to interest his characters. There’s a similar disconnect between what Grussgott wants to convey in his work and the work itself. As long as he stays away from ultimate evil, which swamps him, there are worse problems. In the end, who cares what the artist was thinking?

Grussgott continues at Grey Gallery through June 6. In the Seattle Times, Rachel Shimp sees the show as the artist wants it to be seen.

Great post. Thanks for this.

I found myself being transfixed by those swastika paintings (particular the white one with the weathered wood) but when I got to the center BAM! I got confronted by that swastika. Which is a strange sensation, because obviously swastikas have been in use for centuries for a reason, and what they actually do perceptually (i.e. create the illusion of movement, embody the cycles of time and the coming together of opposites, etc.) has been completely overridden by the symbol’s use by the Nazis. So here is an object that my visual cortex wants to take a ride on, but my brain finds repugnant. (As Prince Harry found out the hard way, swastikas are definitely not cliché.) I’m interested in seeing where Grussgott goes from here, though, as I think some of the problems he’s working with are interesting.

But yeah. Still not sold on the swastika as art, if only because by the time you’ve finished defending your usage, the initial impact has been picked to pieces.