Car consciousness took deepest root on the West Coast, where most of the artists who address it as subject matter have lived. In my version of this art history, everything began with Ed Kienholtz – Back Seat Dodge ’38, 1964, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Before I was 18, this piece was a news story, thanks to its chicken-wire figures having no-rent oral sex. Get a room? Cars are cheaper. To see it, you had to be 18 or an art history student. Being neither, I didn’t qualify but remember thinking, any art the police don’t want you to see has to be worth seeing. It was the point that I began a switch from a primary interest in literature to a primary one in art.

(Click to enlarge images.)

By the early 1970s, J. G. Ballard had begun to think cars as a kind of death-in-life, the equivalent of the cursed ship in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

By the early 1970s, J. G. Ballard had begun to think cars as a kind of death-in-life, the equivalent of the cursed ship in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

(From Testpattern)

Approximately 2 years before the publication of J.G. Ballard’s novel

CRASH! in 1973, filmmaker Harely Cokliss created his short film

“Towards Crash!” for the BBC which featured two parts: one based on

Ballard’s short story “The Atrocity Exhibition”; the other based on

Ballard’s then short story “Crash!”. He cast Ballard himself as both

narrator and lead alongside B-movie actress Gabrielle Drake. The short

captures a more empirical tone as it studies the binary systems of

structure and force, form and desire, the collisions of bodies as the

tools of a modern empire. The visual style seems almost stark compared

to David Cronenberg’s visual imagining of the material in his 1996

full-length feature CRASH, which dwelled more on the mutative synthesis

of man and machine/technology/society at the end of the (previous) century.

I’m

interested in the automobile as a narrative structure, as a scenario

that describes our real lives and our real fantasies. If every member

of the human race were to vanish overnight, I think it would be

possible to reconstitute almost every element of human psychology from

the design of a vehicle like this.

(Photo, New York Times. Dirk Skreber at Friedrich Petzel Gallery through June 27. Review, Ken Johnson: consumerist desire on a collision course with death (To read review, click through from here.)

As

a writer I feel I must try to understand the real meaning of a lot of

commonplace but tremendously complicated events. I’ve always been

fascinated by the complexity of movement when a woman gets out of a

car. Take a structure like a multi-story car park, one of the most

mysterious buildings ever built. Is it a model for some strange

psychological state, some kind of vision glimpsed within its bizarre

geometry?

Jonathan Schipper at Boiler through June 28.

Stephen Andrews, car crash, 2006, crayon rubbing on mylar, from Platform

Stephen Andrews, car crash, 2006, crayon rubbing on mylar, from Platform

What

effect does using these (multi-story car parks) have on us? Are the

real myths of this century being written in terms of these huge

unnoticed structures?

Whiting Tennis, untitled model at Greg Kucera

More

exactly, I think that new emotions and new feelings are being created,

that modern technology is beginning to reach into our dreams and change

our whole way of looking at things, and perceiving reality, that more

and more it is drawing us away from contemplating ourselves to

contemplating its world.

Justin Colt Beckman – road hard and hung up muddy.

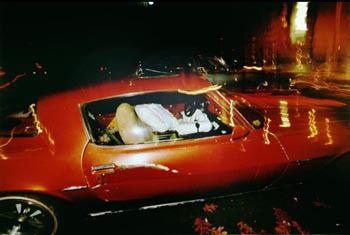

Alice Wheeler, What Women See At Night

Alice Wheeler, What Women See At Night

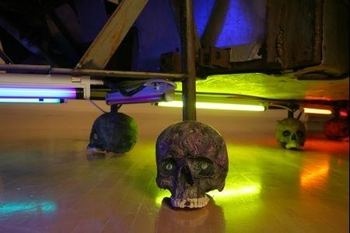

Matthew Day Jackson from The Violet Hour at the Henry, title after Beuys: I Like America and America Likes Me. His muscle car rides on skulls, an allusion to fossil fuel but lit with neon powered by solar panels on the roof. Jackson’s in New York but raised in the Northwest and Northwest in his bones.

Matthew Day Jackson from The Violet Hour at the Henry, title after Beuys: I Like America and America Likes Me. His muscle car rides on skulls, an allusion to fossil fuel but lit with neon powered by solar panels on the roof. Jackson’s in New York but raised in the Northwest and Northwest in his bones.

Hugo Ludeña Evah Fan, Hiccup

Evah Fan, Hiccup Buddy Bunting

Buddy Bunting

Valay Shende – Buddha Right, Marx Wrong

Lee Bul, karaoke machine from Live Forever at the Henry Gallery:

Kathleen Henderson, Pickpocket:

Kathleen Henderson, Pickpocket:

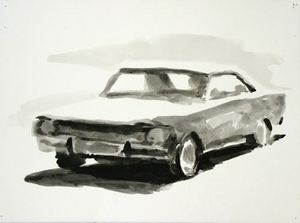

Gonzalo Lebrija, Entre la vida y la muerte (blanco y negro), from Culture Monster:

Gonzalo Lebrija, Entre la vida y la muerte (blanco y negro), from Culture Monster:

Kenneth Baker, SF Chronicle, What is American art, a car perhaps?

Charles

Linder appears to think continually about the zero degree of art and

how to meander just this side of it. But a second question preoccupies

Linder: What makes American art American?At the center of his Gallery 16 show, facing “Take Me to the

Drive-In,” sits “Ghostang” (2006), a bullet-riddled 1965 Ford Mustang

body that Linder retrieved from the desert and powder-coated to

preserve it and revive it as an ambivalent object of nostalgia for auto

and gun fetishists.

As a monument, it

offers us symbolically the vanity of the gunslinger nation, in tatters.

“Ghostang” will remind some viewers of the radiant ’64 Chevy Malibu

that levitates at the end of “Repo Man.”

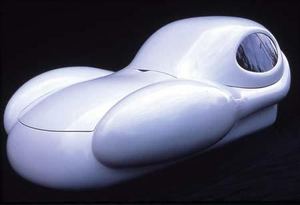

But it makes me think also of “The Master Chassis” (1969), the

legendary dragonfly-sleek car-as-sculpture built by former Berkeley

artist Don Potts. Both Potts’ vehicle and Linder’s might serve as

markers on a distinctly American cultural timeline.

(Shown here as he found it.)

Leave a Reply