Alan Gilbert makes his debut tonight as the New York Philharmonic‘s music director. I wish him the very best of luck.

Alan Gilbert makes his debut tonight as the New York Philharmonic‘s music director. I wish him the very best of luck.

Here’s part of what I wrote about his appointment in Commentary when it was announced two years ago. I haven’t changed my mind since then.

* * *

If you care about the continuing fate of symphony orchestras, museums, ballet, opera, and theater companies, and all the other costly institutions that were the pillars of American high culture in the twentieth century, you must accept that these elitist enterprises cannot survive without the wholehearted support of a non-elite democratic public that believes in their significance.

Leonard Bernstein and Beverly Sills apprehended this, and did something about it. Perhaps more than any other American classical musicians of their generation, they did their best to communicate to ordinary middle-class Americans the notion that the fruits of high culture are accessible to all who make a good-faith effort to understand them. While that may not be strictly or wholly true, it is largely true–and an ennobling idea. I would not be greatly surprised if Sills in particular is remembered for delivering this message long after the specifics of her performing career are forgotten.

Alas, the message has to a considerable extent been forgotten by the orchestra that Bernstein led. To be sure, the New York Philharmonic, like all American orchestras, works hard at cultivating new audiences–but since Bernstein’s time, its efforts in this direction have rarely involved its music directors. Neither Kurt Masur nor Lorin Maazel made any serious attempt to reach beyond the purview of their regular duties to communicate the significance of classical music to a mass audience. Like most conductors of their generation, they saw their job as purely musical, and took for granted that its value would be appreciated by the larger community they served.

Alan Gilbert will not have that luxury. Instead, he must start from scratch. He must realize, first of all, that mere exposure to the masterpieces of Western classical music does not ensure immediate recognition and acceptance of their greatness–least of all when those doing the exposing make it clear that they expect young audiences to like what they are hearing, on pain of being dismissed as stupid.

This condescending attitude is part of the “entitlement mentality” that has long prevented our high-culture institutions from coming fully to grips with the problem of audience development. Too many classical musicians still think that they deserve the support of the public, not that they have to earn it. One of the signal virtues of America’s middlebrow culture was that for the most part it steered clear of this mentality. Its spokesmen–Bernstein foremost among them–believed devoutly in their responsibility to preach the gospel of art to all men in all conditions, and did so with an effectiveness that our generation can only envy.

I sincerely hope that Alan Gilbert will prove to be a great conductor. But I have no doubt that it is far more important to the future of classical music in America for him to be a great communicator, one who finds new ways to do what Leonard Bernstein did so superlatively well in the days of the middlebrow. And I suspect that his will be the harder task: to make the case for high culture to a generation that is increasingly ignorant, if not downright disdainful, of its life-changing power and glory.

Archives for 2009

TT: Snapshot

Stan Getz plays “Blood Count,” Billy Strayhorn’s last composition, in 1990, a year before his own death. The pianist is Kenny Barron:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Where there is great love there are always miracles.”

Willa Cather Death Comes for the Archbishop

TT: Packing and going

The life of a peripatetic drama critic is an endless cycle of ennui and delight. I love seeing out-of-town shows, but in order to get to them, I have to endure the horrors of modern air travel, the only tolerable part of which is the view from a window seat on a clear day. On occasion it also means that I have to tear myself away from Mrs. T, and that’s never any fun: our second anniversary is less than a month away, and the nearer it comes, the closer we grow.

The life of a peripatetic drama critic is an endless cycle of ennui and delight. I love seeing out-of-town shows, but in order to get to them, I have to endure the horrors of modern air travel, the only tolerable part of which is the view from a window seat on a clear day. On occasion it also means that I have to tear myself away from Mrs. T, and that’s never any fun: our second anniversary is less than a month away, and the nearer it comes, the closer we grow.

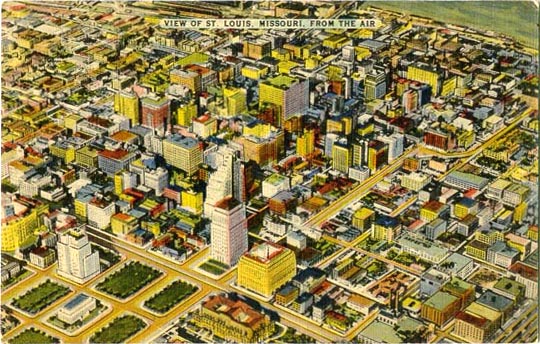

Hence it’s with sharply mixed feelings that I pack my bag this morning and fly alone from Hartford to St. Louis, where I’ll be seeing the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis perform Amadeus tonight. I like Peter Shaffer’s plays and I like St. Louis–I’m going to poke my head into the St. Louis Art Museum, a favorite stop, if my plane lands on time–but I’ve been on the move all summer, and if I had my druthers, I’d just as soon stay home.

The good news (there is always good news) is that St. Louis is two hours north of Smalltown, U.S.A., so I’m going to drive down after the show and spend a few days with my family. I haven’t been there since May, and my mother says she’s starting to forget what I look like. She also claims to have baked a cake in honor of my visit. I’m more inclined to believe the second claim than the first, but either way, it’ll be nice to be in Smalltown again. Mom and I have things to do, none of them significant but all important. For openers, I plan to take her on a long drive in the country, buy her a lunch or two, and tell her all about the premiere of The Letter. I might even sleep late!

The good news (there is always good news) is that St. Louis is two hours north of Smalltown, U.S.A., so I’m going to drive down after the show and spend a few days with my family. I haven’t been there since May, and my mother says she’s starting to forget what I look like. She also claims to have baked a cake in honor of my visit. I’m more inclined to believe the second claim than the first, but either way, it’ll be nice to be in Smalltown again. Mom and I have things to do, none of them significant but all important. For openers, I plan to take her on a long drive in the country, buy her a lunch or two, and tell her all about the premiere of The Letter. I might even sleep late!

See you around.

TT: Almanac

“To fear the worst oft cures the worse.”

William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida

TT: Ten and counting

ArtsJournal, which hosts this blog, turned ten years old yesterday. Doug McLennan, the founding genius and tutelary spirit of the site that Web-savvy people who take the arts seriously visit every day, has blogged about the anniversary here. His post is very much worth reading.

It was Doug who invited me to become ArtsJournal’s first blogger. I went live nine years ago. More than six thousand postings later, Our Girl, CAAF, and I are still going strong, and still proud to be associated with the most important and influential arts-related site on the Web. At a time when newspaper and magazine coverage of the arts is in a tailspin, Doug has changed the face of arts journalism for the better.

I can’t thank you enough, Doug, for making it possible for me to join the revolution. We’re still here–and we’re not going anywhere.

TT: The golden age

In 1977 CBS aired When Television Was Young, a two-hour-long documentary hosted by Charles Kuralt (remember him?) that consisted for the most part of excerpts from kinescope recordings of live TV broadcasts that originally aired between 1949 and 1961. The programs include Captain Kangaroo, CBS Reports, Douglas Edwards with the News, The Edsel Show, The Ernie Kovacs Show, The Garry Moore Show, The Goldbergs, The Honeymooners, Howdy Doody, I Love Lucy, Kukla, Fran and Ollie, The Mickey Mouse Club, Mary Martin and Noël Coward: Together With Music, Mr. I. Magination, Playhouse 90, The Red Skelton Show, See It Now, The $64,000 Question, Studio One, Suspense, Texaco Star Theater, Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, You Are There, and Your Show of Shows. Some anonymous benefactor has posted the whole show on YouTube in seven installments. I commend all seven to your attention.

Don’t be thrown by the fact that the program gets off to such a slow start. Television used to be like that:

TT: Three for three

Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong has received yet another pre-publication rave, this one in the August issue of Booklist, the magazine of the American Library Association. Here’s an excerpt:

Teachout excels when explaining such things as why the early Armstrong recordings with his Hot Five and Seven groups are cornerstones of jazz. He provides a fresh musician’s perspective when analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of such foundational compositions as “Heebie Jeebies” and “West End Blues.” Teachout also argues for the merits of Armstrong’s popular music done in the manner of Bing Crosby. And he disagrees with the later bebop players who didn’t like Armstrong’s act, which they viewed as pandering to white audiences. What they didn’t understand, and what Teachout vigorously argues while simultaneously revealing the soul of his subject, is that being an entertainer was wrapped up in Armstrong’s personality and genius. Ultimately, Teachout’s fine biography shows how much of Armstrong’s love of music–and people–was behind that signature million-watt smile….

Nice, huh?

* * *

A boy must peddle his book, so I now have a personalized author page at Amazon. To see it, go here.