The annals of the Harlem Renaissance include heated debate over the practice of turning African-American spirituals into concert songs.

Zora Neale Hurston Hurston heard concert spirituals “squeezing all of the rich black juice out of the songs,” a “flight from blackness,” a “musical octoroon.” She listed Harry Burleigh among the offenders.

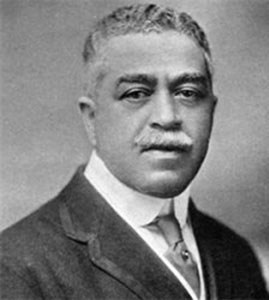

But without Burleigh there would be no “Deep River” as sung by Marian Anderson.

Angel Gil-Ordonez, the inspirational music director of PostClassical Ensemble, calls Burleigh one of our “lost causes,” along with Bernard Herrmann, Lou Harrison, and Silvestre Revueltas — with Arthur Farwell coming up in October.

What Angel means, really, that these are delayed causes – that Burleigh will ultimately become known as an American musical hero, that Herrmann will remembered for more than his supreme film scores, that Harrison will be widely performed east of California, that Revueltas (notwithstanding being Mexican) will take his place as a twentieth century master – and that Arthur Farwell’s “Indianist” compositions, in parallel with Bartok abroad, will transcend their stigma of “appropriation.”

I am not sure what, exactly, “rich black juice” might be, but there is a lot of it when Kevin Deas sings Burleigh’s “Steal Away” – as he did last Thursday night in a PostClassical Ensemble program we called “The Spiritual in White America.” It sounded like this.

That was at the Phillips Collection – which in addition to its landmark collection of twentieth century American paintings boasts a venerable music series situated in an intimate, wood-paneled music room enhanced by a rotating selection of great visual art.

In such a space, the impact of Burleigh’s settings – both solo and choral – was immense. On the same program, we heard readings by Hurston, W. E. B. Du Bois and Antonin Dvorak (whose assistant Burleigh was in New York’s National Conservatory). That is: we sampled a debate over appropriation. In the ensuing discussion, a member of the audience called this the most memorable music-education experience he had encountered since the days of Leonard Bernstein.

Burleigh’s spiritual arrangements (some of which deserve to be called “compositions”) were juxtaposed with remarkable arrangements by composers black and white, including William Dawson and Michael Tippett.

Hurston is correct: none of these concert versions of plantation song evoke the wild grief and ecstasy of enslaved human beings laboring under the lash of white America. She rightly misses the “jagged harmony,” the dissonance and spontaneity of singing in the field, where “each piece is a new creation.” Nor – as the African-American composer/impresario Nolan Williams pointed out in an acute post-concert discussion – does the spiritual in concert truly evoke the sheer devastation of stolen lives.

And yet, in live performance, Burleigh’s relative simplicity and directness of expression impart a timeless dimension. More than subsequent concert renditions, they manage to convey the immediacy of the vernacular.

Take “Deep River.” It was first set down (in an 1877 Fisk Jubilee Songbook) as a “church militant” spiritual. So far as I am aware, the once famous black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was the first to capture “Deep River” for the concert hall. He slowed it down and “dignified” it as a 1904 solo piano piece. To my ears, the eight-minute Coleridge-Taylor “Deep River” is diffuse. And its decorum registers what Hurston called “a flight from blackness.” Burleigh’s final setting for voice and piano (1915) is by comparison singularly concentrated: thirty-one measures lasting less than three minutes. But everything is there. Even the chromatic harmonies, even the keyboard counter-melodies are radically concentrated. It attains an elemental force.

Here is Kevin Deas singing Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River” three days ago at the Phillips Collection. It has been my privilege to accompany him in concert for some dozen years.

Cultural Appropriation isn’t really a thing. Because it will always be ignored by actual artists in all fields who are moved to create something. I suppose those who don’t understand this can make annoyed noises among themselves but it will never matter.