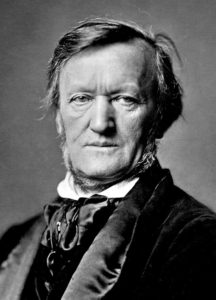

Was Richard Wagner a “monster”? No so far as I can tell. Here’s my book review of Simon Callow’s opportunistic “Being Wagner” in this weekend’s “Wall Street Journal”:

Was Richard Wagner a “monster”? No so far as I can tell. Here’s my book review of Simon Callow’s opportunistic “Being Wagner” in this weekend’s “Wall Street Journal”:

In 1866, a Munich newspaper reported that Minna Wagner, the recently deceased wife of the composer Richard Wagner, had lived in “direst penury.” She was reduced to accepting poor relief notwithstanding “momentary” support “on the part of her [estranged] husband.” Never mind that a letter signed by Minna herself had stated that the voluntary annual allowance she received from her husband had permanently freed her from financial cares. The newspaper claimed— falsely—that the letter had been written for her in order to conceal the facts.

This instance of fake news was not a novel occurrence in Wagner’s harried life. And 135 years after his death he is harried still by the mandatory cartoon that makes him a “monster.”

There are three basic sources for depicting Wagner the man. First there are his operas, which remain as vital to the Western cultural canon as ever. Second there is his personal behavior, copiously recorded in letters and other written accounts. Third there are his essays, notoriously including the egregiously anti-Semitic “Judaism in Music” of 1850. Though any portrait of Wagner that begins with the essays will necessarily be prejudiced against him, this is a typical route. There are even influential writers on Wagner who disdain considering the operas altogether.

As it happens, the operas are saturated with complex self-portraiture, and a governing motif is Mitleid—compassion. Like it or not, Wagner’s characters specialize in empathetic comprehension. And any perusal of Wagner’s more than 12,000 letters will confirm that this humane aptitude was not foreign to Wagner the man. His many heart-breaking letters to Minna document astute, guilt-ridden understanding of their failed marriage, an understanding that impelled him to generously support an unhappy and unpleasant woman even when his own financial resources were nearly barren.

And Wagner was uncommonly rich in friendships. According to the monster cartoon, these friendships were all fundamentally exploitative. But consider the impresario Angelo Neumann, who left a book-length account of his eventful personal and professional relationship with the composer. Why was Neumann so dedicated to Wagner? Because he recognized his genius. Because Wagner’s prickly company was galvanizing. And because Wagner’s torrent of human feeling was endearing. Neumann, by the way, was Jewish.

The Wagner literature disposes of Neumann, Hermann Levi and other Jews in the Wagner orbit as studies in self-hatred. Such an approach is patronizing and obtuse. A fairer question is why Wagner wrote and spoke such intolerable nonsense about Jews. Reasons of a sort may be adduced. But the simple fact is that his evil anti-Semitism does not align with his actual behavior. That behavior is often elusive because Wagner was a consummate actor. He wore many faces. Was he a master imposter, or was he (as his letters suggest) helplessly inhabited by a repertoire of demonic personae?

That the actor and author Simon Callow should be enticed by such a figure is only natural. His own distinguished career includes one-man shows aimed at illuminating Jesus, Shakespeare, Dickens, Oscar Wilde—and Wagner. He has now turned his Wagner performance into a reckless little book that stylishly recycles the standard monster caricature.

In “Being Wagner,” Mr. Callow writes early on that his main source was the composer’s “own words, in his copious published writings. . . . Above all, I found that my most sustained sense of the man came from a book I had somewhat dreaded reading—his two-volume autobiography, My Life.” Mr. Callow’s surprise that the book “turned out to be as vivacious and candid as the greatest artists’ autobiographies” says it all. Everything endearing about Wagner—including the “surprisingly punctilious” pension he paid to Minna—strikes Mr. Callow as uncharacteristic. He is himself a victim of the monster myth, which he inserts as a corrective whenever his Wagner portrait turns too pleasant.

In particular, Mr. Callow is seduced by the ironic panache of Wagner’s self-descriptions, the most memorable of which are nearly Dostoyevskian exercises in hilarious self-humiliation. Mr. Callow’s compression of these stories—their merciless expansiveness is itself comedic—does not do them justice. A greater injustice is that the derisive tone Wagner applies to himself turns patronizing when applied to Wagner by another, lesser writer.

That Mr. Callow’s breezy portrait of Wagner is disrespectful will not be noticed by readers brainwashed by the monster cartoon. A small minority will think twice and recognize that Mr. Callow is glibly passing judgment on a supreme psychologist whose distressing and self-distressing gift was to peer more profoundly into the human psyche than any of his contemporaries—a predicament that left him lonely, restless and insatiable.

The first singer to portray Tristan was Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld, a prodigious artist whom Wagner regarded as a rare friend. He died suddenly, age 29, days after the premiere. Wagner confided to his diary: “I drove you to the abyss! I was used to standing there: my head does not swim. But I cannot see anyone else standing on the brink: that fills me with frantic sympathy.” Anyone who thinks those words are hyperbolic does not know the existential void into which Tristan plunges.

Central to Wagner’s identity was his unwavering recognition of the magnitude of his genius and the conditions for its proper cultivation. He was convinced that the world owed him a living. If he were to pursue conducting, or some other gainful employment, he could not compose. As a result, he was frequently impoverished and ill, vilified and derided. His enemies were real, powerful and numerous. Mr. Callow here discovers “a beady instinct for protecting his gift, his genius, and what fed it.” He argues that when Wagner “sued for favours, he had two modes: one, grovelling, the other haughty.” Wagner was himself the keenest analyst of his extreme instability. “What makes you see or wish to see a wise man in me? How can I be a wise man, I who am myself only when in a state of raving frenzy?” Mr. Callow cites this frank testimony to an intimate correspondent only to discover evidence of “the unrelenting soap opera” of Wagner’s “emotional life.”

Even in a book eschewing musical analysis, Mr. Callow is betrayed by his ignorance of music. Did Wagner retouch Beethoven’s orchestration because “Beethoven had, in Wagner’s view, got it wrong”? No, like many conductors afterward, he felt the need to accommodate changes in instruments since Beethoven’s day. Did he create “the notion of the conductor as puppet master”? No, as he explained in his pamphlet “On Conducting,” Wagner realized that a new kind of music—marshaling larger forces and pervasively flexing tempo and dynamics—required a new kind of proactive conductor. Did the tenor Albert Niemann trim the role of Tannhäuser because he figured “the sooner the inevitable catastrophe was over, the better”? No, Niemann (a supreme singing actor) felt that he could not sustain the opera’s last act without abridging the second-act finale.

As for “Tannhäuser” itself, did it arise from “the compost heap” of Wagner’s imagination? Is “Die Meistersinger” “everything Wagner said an opera shouldn’t be”? Does the “Ring of the Nibelung” amount to “self-celebrating Teutonic tub-thumping”? Come on. Summarizing the affect of it all, Mr. Callow says that Wagner’s audiences are impelled toward mass submission, not the state of active critical engagement provoked by Bertolt Brecht. Is he actually not aware that the “Ring” and “Tristan” have excited more intense critical commentary than the fading Brechtian corpus ever will?

The closest Mr. Callow comes to plausibly evoking Wagner the man is when he quotes those who admired him. Here, for instance, is the dramatist Édouard Schuré: “To look at him was to see turn by turn in the same visage the front face of Faust and the profile of Mephistopheles . . . one stood dazzled before that exuberant and protean nature, ardent, personal, excessive in everything, yet marvellously equilibrated by the predominance of a devouring intellect.” And here, balancing the books, is Mr. Callow’s follow-up: “Wagner had, it seemed, no inhibitions whatever, his qualities and defects on open display, to the delight of some and the deep repugnance of others.”

Predictably, Mr. Callow more extensively considers “Judaism in Music” than any of the operas. He blithely clinches the Wagner-equals-the-Third Reich equation: “Hitler-like,” Wagner spewed poison—“the notion of the Jews as a rotten part of the body politic which needed to be excised”—that was “enthusiastically taken up by the Nazis.” In fact, whether a straight line runs from Wagner’s brand of odious anti-Semitism to Hitler’s murderous Judenpolitik is a necessary question long debated by historians, with no consensus in sight.

It is wholly understandable that the shadow of the Holocaust has for more than half a century blackened our view of Wagner the man. Someday a revisionist wave will surface. But not yet.

Mr. Horowitz’s books include “Wagner Nights: An American History.” His book-in-progress is “Understanding Wagner.”

I have attended performances of much of Wagner including the Ring. Never have I heard such bombastic, boring music. I prefer Nancarrow and Legiti.

Two quotes about music:

“Wagner’s music is better than it sounds” – Mark Twain

“If it sounds good, it is good.” Duke Ellington

I’ve never found Wagner’s music in any way “boring .” You might call it “bombastic ” ,but it is also often gentle and lyrical .

It is true that the full extent of the Hitler/Wagner connection will be in future histories. Interesting parts of the puzzle are missing for now. One of Wagner’s descendants, Amélie Lafferentz (b. 1944) is in possession of 278 letters exchanged between Hitler and her grandmother Winfred Wagner. Amélie has never allowed scholars to view these letters, which are very likely of important historical value, especially for Hitler biographers and historians of the Third Reich, to say nothing of the history of Bayreuth. Winifred’s husband, Siegfried, who was Wagner’s son, was secretly bisexual and showed little interest their marriage. It was rumored that Winifred and Hitler were lovers. In 1933 there were even rumors of a possible marriage. None of this history will be confirmed until the 278 letters between Winifred and Hitler are released. They might also answer the question about how much Hitler’s Judenpolitik was influenced by Wagner.