When a pianist plays the piano, when a violinist plays the violin, when a conductor conducts an orchestra, the performer channels music through a network of personal traits. This should be self-evident.

It has always seemed to me, for instance, that Artur Rubinstein was an exceptionally wholesome artist. Listen to Rubinstein’s recordings of Chopin waltzes and you will discover (however subliminally) a broad emotional vocabulary at play – and a conscious application of specific emotional states to specific waltzes. The entire exercise is one of cultivated civility and worldly maturity. We are sampling the performer’s persona.

I have two favorite studio recordings of Schubert’s “Great” C major Symphony: Wilhelm Furtwangler with the Berlin Philharmonic and Josef Krips with the London Symphony. Back in the days when such things mattered, these were known readings. (As a young New York Times music critic, I once wrote an assessment of the Furtwangler performance. A reader wrote to state his preference for Krips, and explained why.)

Furtwangler’s Schubert C major is epic and demonic. Krips’s is warm and songful. In affect, these readings have little in common. They both deeply engage with the scope and pathos of a score that – as so often in Schubert – is uncannily polyvalent.

It is easy to trace the lineage of these readings. Furtwangler’s feasts on Germanic Innerlichkeit, and also precepts of interpretation preached by Richard Wagner. A constant flux of tempo calibrates flow, structure, and climax. Krips’s interpretation extols Viennese gemutlichkeit; Furtwanglerian interventions, in such a context, could only get in the way.

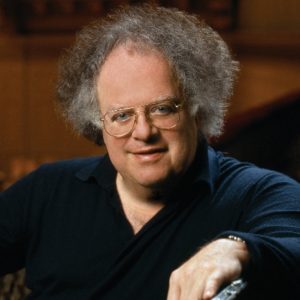

James Levine’s high reputation as a musical interpreter has always seemed to me a frustrating mystery. Whether of Verdi or Wagner, his performances evinced no lineage. And his persona, so far as I could tell, remained a blank.

When he first arrived at the Met, he whipped the orchestra and chorus into shape and refreshed the repertoire. No doubt he was a facile musician. Even as a young man, he had evidently acquired a lot of repertoire and practical experience. His readings were typically intense, massive, and loud, sometimes to the point of brashness. In subsequent decades, he mellowed. But I never heard from Levine much evidence of emotional variety or depth. According to my experience, he had little capacity to organize a long stretch of music, or to powerfully shape a climax or pregnant phrase. He did not produce a sonic signature – as Furtwangler and Krips did; as Gergiev and Muti do. He did not possess an ear for color or texture.

If you listen to the Met broadcasts of Ettore Panizza and Artur Bodanzky – broadcasts I have written about in this space – you’ll hear conducting (and orchestra playing) of a higher caliber. And Panizza and Bodanzky stood on the shoulders of giants: Seidl, Mahler, Toscanini. The early Met was a conductor’s house.

Let me share a couple of vignettes.

In the 1980s I was artistic advisor to the Schubertiade at the 92nd Street Y. The central participant was the baritone Hermann Prey, invariably partnered by Leonard Hokanson. Hokanson had studied with Artur Schnabel. His Lieder accompaniments were highly shaped, highly inflected interpretations; I would call them “Schubertian” a la Schnabel. He and Prey worked seamlessly together. Then it happened that Prey was offered a Carnegie Hall recital, singing Schubert. He replaced Hokanson with James Levine. Levine and Prey also worked seamlessly together. But Levine’s accompaniments, next to Hokanson’s, were stiff and generic. The performances were forgettable.

A little before that, when I was a critic for the Times, I hung out at the home of a psychoanalyst who would rent an extra bedroom. His tenant, for a period of time, was a young man from within James Levine’s inner circle. I was recklessly frank in sharing my poor opinion of Levine’s performances. On one occasion, I suggested that Levine (then in his thirties) lacked sufficient life experience to conduct opera at the highest level. Opera is theater, after all. You don’t entrust Hamlet to someone who doesn’t know life. His quick response told me that this question had been asked and answered before – the answer being that breadth of “life experience” wasn’t a valid consideration in the world of classical music performance.

I shared these views the other day with a member of the Met orchestra. He contrasted James Levine with conductors who command a “complete” concept of an opera. He mentioned Carlos Kleiber and Daniele Gatti. My Times Literary Supplement review of Gatti’s Parsifal appeared in this space; it made the Levine Parsifal sound square and cumbersome. I did not hear Kleiber’s Rosenkavalier at the Met. My friend remembers Kleiber instructing the orchestra that the music accompanying the Marschalin must shimmer like chiffon, creating a veil through which this character’s fading beauty could be apprehended.

On youtube you can watch Kleiber rehearse the overture to Die Fledermaus — a supremely worldly operetta. After three notes of the first, teasing theme in the violins, he stops the orchestra to ask for a rendering “a little more dishonest.”

There is a ripeness in that exhortation that my ears never detected in the performances of James Levine.

I studied with the great Leonard Hokansen.

He is sorely missed. A great musician and teacher.

I’ve never understood how people could not hear a connection between art and the person who created it. It’s not always so direct or obvious, but its usually there. Wagner’s excesses, Verdi’s human dignity, Britain’s homosexuality, Ives’ New England spirit, the way Copland combined a sense of majesty and compassion. These things reflect a human’s identity.

I think of Oscar Wilde and the meaning Salome had for him, confusion about forbidden impulses, and how he even hid it behind a sort Belle Époque facade. And I hear how Strauss didn’t have those feelings, but saw a pseudo-scandalous spectacle that could be exploited. One can hear Holst’s fine British handlebar mustache music. Or Bach’s very Lutheran cosmic sewing machine. Life creates art, and art creates life. Thanks for the interesting comment.

“Wagner’s excesses, Verdi’s human dignity, Britain’s homosexuality…”

Thank you. That was wonderful 🙂

I’m sorry , but with all due respect , your evaluation of James Levine as a conductor and musician is terribly unfair I have experienced this live performances and recordings for at least as long as you have , but I have always had a far more favorable impression of his conducting than you , and many critics and opera lovers would agree with me .

Whatever his flaws as a human being , he is a very great conductor and musician and his accomplishments at the Met have been colossal . No ,he isn’t perfect and not every performance he has given has been superlative , but the same could be said about any of the great conductors of the past , and I am convinced he is their equal, and great in his own way . He is also an outstanding conductor in the concert hall .

He has been able to bring such outstanding conductors as Carlos Kleiber , Simon Rattle, Daniel Barenboim, Riccardo Muti, Gergiev , and others to the Met , and I believe the overall caliber of conducting at the Met is higher than ever before . And remember , back in the so-called “golden age” of the Met , undistinguished hack routine opera conductors were the norm rather than the most eminent ones .

Levine was a protege of George Szell and that extremely demanding mentor would never have chosen him to be an assistant conductor of the Cleveland orchestra if he were not an outstanding talent .

Over the years , Levine has given so many truly great performances of operas by composers as diverse as Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, Berlioz, Richard Strauss , Alban Berg, Schoenberg , Debussy , Puccini, Weill,

Smetana, Tchaikovsky , Offenbach , Stravinsky, Beethoven , Corigliano, Harbison and others at the Met .

To dismiss Levine so lightly is to do a grave injustice to him .

I so agree with you! It is wrong to tear apart the musical genius of such a proven, fine conductor as is Maestro James Levine! The Maestro contributed an outstanding legacy of musical achievements throughout his career at the Metropolitan Opera. I well remember how the orchestra sounded and how disorganized musical preparation was, at the Metropolitan Opera, before Maestro Levine’s tenure as Music Director. I also remember when George Szell chose James Levine as an Assistant Conductor ( I lived in Cleveland at the time), and noted how well Maestro Levine conducted Opera and instrumental performances in the Cleveland area.

And especially to do so at this time. Cowardly, quite a comment on the character of the critic. A critic, who made his name after Toscanini died by erroneously complaining that the Maestro did not play “new” music. Toscanini had premiered many works of Puccini, Ravel, Debussy, and done works of Verdi, Catalsni, Respighi while they were still alive. Not to mention Americans George Gershwin, Ferde Grofe, and composers associated with the NBC, which he began conducting at 67.

The very interesting and perceptive comments of Mr. Horowitz can be equally said of some of the orchestral work prevalent in the United States; brashness and superficial vigor seems to supersede depth and intellect (which is why many pine for some of the musicians of the past). It would be interesting to discuss the factors that cause these dichotomies between past and present.

I find this article interesting and agree on the whole on the points of artistic persona and its influence on the artistic output/performance. I am however not well acqauinted with Mr. Horowitz’s reviews of Mr. Levine’s performances in the past. I think it could be interesting to see if any of those reviews brought up these points during the time when Mr. Levine had not been kicked to the curb but was viewed as one of the truly great artists of his time?

I’ll speak just for myself. Not only was I saying it in real-time (and many friends agreed with my assessment, though not all), but my husband refused to attend any more James Levine performances after a few years’ worth of them because he couldn’t stand Levine’s performances. And he didn’t. I still kept going, but by year 5 or so that was not more than 1 concert a season, out of the 10-12 attended.

Singularly perceptive article.

I can only speak first-hand of James Levine’s tenure with the BSO, as I’m a long-time BSO subscriber and attendee. Let’s just say I was not a fan of the Levine era. To Levine’s credit, he raised the performance standards of the orchestra significantly during his tenure. They sounded like a different orchestra by the time he left than when he came.

But as an interpreter of the tonal symphonic repertoire, based solely on what I heard, Levine wasn’t even third-rate. I came up with a nickname for him: King of the Phrase. Levine could do *tremendous* phrases. Loud to soft, soft to loud, slow to fast, etc. Really, the phrases were meticulously crafted. But to what end? Everything existed in the moment. There was no long arc, no stringing together of the phrases into a coherent narrative that had a beginning, a middle, and an end, no poetry to any of it. It just lived in the moment, and then it was over. I can name so many warhorses that in Levine’s hands were worse than forgettable: Brahms 2, Brahms 3, Dvorak 8, Schubert 9, Beethoven 7, anything Mozart, Schumann 2, ad infinitum. I can honestly think of no single performance of Levine’s that I loved during his tenure with the exception of Wagner’s Flying Dutchman. I kept asking myself, how does this man have such a reputation as a great conductor?

My husband had a different name for it. He’s a physician, and he comes at it from a different perspective than I’ve ever heard anyone ever analyze James Levine’s music-making before. He said, “His music plays as if he and it are on SSRIs (the class of anti-depressants such as Prozac and Zoloft that are standard of care). Everything is leveled out–no real highs, no real lows, it just moves forward.” Neither of us heard much of an emotional response in anything from Levine’s baton. It just went forward, without any real emotional engagement, and then it was done, followed by the obligatory standing ovation.

I definitely do not know the opera repertoire as I know the orchestral repertoire. I can’t say I was blown away by James Levine’s Wagner as seen/heard in the Live in HD transmissions. My best guess, at the end of the day, is that little will be remembered of James Levine’s music-making. What will instead be remembered are his institutional-building capabilities, and his interest in young boys.

I agree with you that there is something truly generic in Levine’s performances that inhibited their quality, but there was an interview in the late 70’s that Levine did with Bernard Jacobson, in which he talked about the human qualities of Mozart and Verdi, and how of all composers they come closest to the completion of the human experience that one finds in Shakespeare. In the music which he obviously felt the greatest affection –

Mozart and Verdi, perhaps Strauss and Berg as well, Levine did come alive and think in human terms. No, he was assuredly not Panizza or Kleiber, neither were Toscanini or Szell, and Levine did have a gift for making that Szell/Toscanini level of orchestral discipline at least sound much warmer than either of those predecessors did. I doubt Levine ever thought as deeply as many conductors of similar eminence, and not deeply enough to deserve his eminence, but he was not quite a blank either. Also, I would hardly use Muti as an avatar of deep and personal interpretation outside of a similarly small band of composers.

I fear virtually everything about James Levine in Mr Horowitz’s piece is complete b*ll*cks. I have heard many performances of great individuality and humanity from Levine and I have the recordings to prove it. The paragraphs about Levine are so loaded with words such as ‘facile’ and ‘brashness’ that they amount to a massive pseudo-intellectual attempt to kick the man when he is down. If Levine has sinned, that is one thing, but to say, in effect, ‘I never thought much of him anyway’ is to shoehorn the poor chap into one’s own overtight prejudices. By the way, I disagree with most of the other opinions in the piece too.

When I heard Levine conduct Der Rosenkavalier at the Metropolitan back in ’00 (or ’01?) he had no clue about the proper Strauss style. The orchestra played for him with a bloated, muscular and agressive sound that robbed us of the score’s magic. It didn’t help that the cast was equally unidiomatic and charmless. It was a very American Rosenkavalier, fit for the hustle and bustle of Manhattan or the trading floor of the NYSE but had little to do with Vienna. Contrast that to the very echt Viennese Rosenkavalier that unsung guest conductor, the Czech Jîri Kout, directed around the same time. It made all the difference. Night and day. In his hands the score sparkled with wit and charm and the orchestra corresponded as to the manner born. It also helped greatly that Kout was surrounded by a far superior cast of singers.

Whatever your thoughts are about James Levine and you certainly are entitled to them and by all accounts you are someone who merit a serious listening. On the other hand, is this the right time to express them? When someone, a human being is down and being kicked by every minor figure in the music world? Why join these people? Why not let him disappear into whatever dark corner he wants to be in to lick his many wounds. Is there no humanity left in this business? Or should one say, is there no shame left?

It’s not like anybody here has not said what people have said about Levine’s performances many times. Whatever else Levine is or is not, he is a public figure, and every public figure runs the risk of their work being interpreted in the light of new information, no matter how unflattering.

Levine is a member of the pantheon of great conductors, no amount of dissenting voices will ever take that away from him. His musical achievements, even if inconsistent, are vast. Horowitz is a minority opinion, but he’s one of the great music journalists of our time, so for god’s sakes just let the man speak his peace.

Whatever else is going on here, we are basically writing the obituary of a long and storied career. Whether he deserves to or not, Levine will never conduct anywhere in the West again. This is the time to take stock of his career and achievements while the memories are still fresh as we would any artist whose career has just ended.

Keep voicing your opinion Mr. Horowitz. What you have to say is too valuable to keep it to yourself.

I spent an afternoon with an Ex-principal of the MET orchestra decades ago. I expressed similar comments on Mr. Levine’s interpretive gifts as those of Mr. Horowitz. They were met with total astonishment on the part of my host. It was as if he had never heard a negative opinion on Levine’s performances. He, sitting in the orchestra, had a completely different appraisal of Levine. I always felt that being a member of that orchestra was a singular accomplishment which engendered a kind of fidelity that was sincere and stemmed from the way in which these instrumentalists were treated by Mr. Levine. In a word, he knew how to (and whom to) appeal to so as to cement his position in that organization. And this won him an admiration that was less founded on his ability to create a singular musical experience than to convince his performers that they had created a singular musical experience. Audiences nowadays are easily molded. Let’s face it, if you’ve just spent $1000.00 on tickets to an operatic performance you do not want to think it was a waste of money! I, too, have many recorded performances, and have listened to thousands of others, being 60+ in years. I was a regular attendee at the MET from 1975-1991. I sat through many of Mr. Levine’s performances. Regrettably, Mr. Levine’s foot print, regardless of his current situation, will be but a footnote due to Mr. Horowitz’s keen observation that “…his persona, so far as I could tell, remained a blank…(and) the performances were forgettable.” Simply put, I recall how differently I felt after (and still do to this day!) a Boehm, Leinsdorf, Pritchard, Santi or Kleiber performance.

The person that you really should be critical of is the old man that accused James of treating him in appropriately therefore ruining his career, and everything his entire life was about. Why the world just wants to shame everyone for one thing or another instead of celebrating each other’s other’s geniuses is only holding the advancement of humanity back.

I find it fascinating that so many now feel, finally comfortable to take the conducting achievements of Levine to task, particularly the person above who claimed he was “less than third rate” and all he will be remembered for is his penchant for young boys. While not every performance was great . . . a Brahms 2nd, and an Andrea Chenier both tanked on arrival . . . many were among the greatest evenings of my life. in particular, I recall a Wozzeck that every phrase from start to finish tied the harrowing drama together, all leading up to the final interlude that destroyed an opening night crowd. Alan Held and Katarina Dalayman responded to his sensitivities and gave among the best performances I’ve experienced of Berg’s harrowing masterpiece. In Boston, Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder elicited a similar response and the work between Levine and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson as the Wood Dove (in one of her final performances) was of such intimacy one felt as if intruding in on the most private and heartbreaking of moments. I can recall many such evenings with Levine. Not all of us respond to a conductor’s ways or mannerisms, but to denigrate one who’d achieved so many awards and accolades as a “hack” or “third rate” is the height of hubris.

Thanks for your thoughtful post, Joe.

I completely understand disliking, and even feeling an aversion to, the work of an artist, even one with unmistakable talent, such as Levine. Some work speaks to you and some doesn’t. Some does at first and pales later on with familiarity. However, I do not agree that Levine’s work is shallow or unwholesome because he has, by current standards, an unhealthy predilection for young boys. Rather, if his work is either of those things, it is more likely because he has been pulled in too many directions, with running an opera company, accompanying singers, preparing productions, making recordings, that the music didn’t always get his last ounce of attention. It’s surely his fault that he overbooked his professional life, but he’s far from the only one. In the old days, Rachmaninoff practiced on a dummy keyboard while taking the ocean liner to the US. Now, someone like Levine will have a rehearsal for one production in the morning, another in the afternoon, and accompany a singer in the evening, and not necessarily in the same city.

Too many things going on? Welcome to the modern world and the musicians who reflect our time. There is a reason we turn to conductors like Furtwangler and pianists like Rubinstein — because the world in which they were born and lived doesn’t exist anymore. We crave what they produced, and we are lucky to have so many recordings of their work. But they weren’t great because they did or didn’t desire boys.