What did the legendary Russian experimental theater director Yevgeny Vakhtangov (1883-1922) have in common with Porgy and Bess, Oklahoma!, and Carousel? The immigrant director of these landmark Broadway productions, Rouben Mamoulian, was to some degree a Vakhtangov disciple.

Mamoulian took Broadway by storm in 1927 with his staging of Dubose Heyward’s novel Porgy. At the age of 30, he was an overnight star, an apostle of radically integrated musical theater imposed by a singular directorial vision. Mamoulian’s fame drove him to Hollywood, where he hired Richard Rodgers to through-compose music for Love Me Tonight (1932) – a supreme musical film that subverts and surpasses Ernst’s Lubitsch’s film musicals. It may be plausibly inferred that Mamoulian introduced Rodgers to the strategies and ideals that would make Oklahoma! and Carousel Broadway break-throughs. In short: Mamoulian is a forgotten hero of American musical theater – and the influence of Russian experimental theater on mainstream Broadway is a story even more forgotten.

I became aware of the magnitude of Mamoulian when writing Artists in Exile: How Refugees from European War and Revolution Transformed the American Performing Arts (2008). Subsequently, I plundered the Mamoulian Archive at the Library of Congress and discovered that Mamoulian’s impact on Porgy and Bess was more fundamental than anyone had imagined. He single-handedly turned Heyward’s novel into a musical redemption drama (Porgy the play was already full of singing) eschewing Heyward’s efforts to “authentically” represent the African-American Gullahs of Charleston’s Catfish Row. (I reported these findings in “On My Way” — The Untold Story of Rouben Mamoulian, George Gershwin, and “Porgy and Bess.”)

How indebted was Mamoulian to Vakhtangov? It’s an elusive topic because Mamoulian preferred to present himself to Americans as a self-created genius. And yet descriptions of the Vakhtangov studio – of which Mamoulian was part sometime during his Moscow years 1915-1918 – fit the Mamoulian mold. Vakhtangov was a Stanislavski disciple who rejected Stanislavski’s verisimilitude. Rather, he espoused “fantastic realism” wedded to “total theater.” Like Stanislavski, he cultivated an aesthetically bonded community of actors. Unlike Stanislavski, he was obsessed with choreographing sound and music – with rhythm and tempo. His detractors complained of a surfeit of detail, of elaborate artifice and a failure to project interior feeling. All of this fits Mamoulian – especially his hyper-ambitious Porgy and Porgy and Bess productions, preceding a long and erratic decline accelerated by the influence of Hollywood and a bad marriage.

A century later, Moscow’s Vakhtangov Theater endures. Rimas Tuminas, its Lithuanian artistic director since 2007, is today a reckonable force in Russian theater. His award-winning Vakhtangov production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, first given in Moscow in 2009, is currently enjoying a short run at New York’s City Center. To what degree Tuminas’s Vakhtangov Theatre retains the imprint of Yevgeny Vakhtangov I have no idea. But this Vanya seems to fit the bill. It rejects verisimilitude. It embraces total theater and a consuming directorial vision (what we today call Regietheatre). And, most strikingly, it integrates music more pervasively than any production I have ever encountered of a classic play.

In fact, a musical score composed by Fautus Latenas is a constant ingredient. Latenas has supplied a series of minimalist mood vignettes, each a short refrain incessantly repeated. The volume is usually low, but there are also crescendos and climaxes aligned with Chekhov’s text. This could be a recipe for kitsch if the score were deployed to underpin the mood on stage. But that mood is polyvalent, and more often than not the musical component is ironic. Sonia’s excrutiating scene with Dr. Astrov, for instance, is played to a tart waltz.

In a useful interview in the City Center program book, Tuminas says:

“Chekhov looked at people’s desire to be happy and thought, ‘My god, you are so funny! You daydream and expect happiness, knowing full well that it’s impossible!’ He sees all these poor, holy crearures who want something and are reaching for something even though there’s nothing up ahead, and it makes him smile a kind, forgiving smile. That’s probably why there’s so much humor in his plays. It’s deeply hidden, but if we can grasp it, perhaps we’ll understand something important about our own lives.”

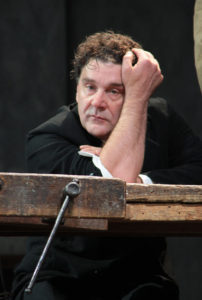

I would not call the humor in Tuminas’s Uncle Vanya “deeply hidden.” Sergey Makovetskiy, who plays Vanya (in the photo above), is virtuoso mime. Limping and disheveled, ill-attuned to life’s requirements, he projects the pathos of a W. C. Fields or Buster Keaton. A reading more distant from Michael Redgrave’s famous English-language Vanya is scarcely imaginable. At the play’s beginning, the news of the Professor’s arrival animates Vanya hilariously. The pompous formality of the entrance itself, accompanied by a fawning retinue, equally invites laughter. But this tone is not sustained. The contradictory vectors dialectically at play – humor vs. pathos, music vs. action, attraction vs. repulsion among the variegated dramatis personae of the Serebryakov estate – are at all times exquisitely unpredictable.

The Professor himself is cast against type. Vladimir Siminov is a big, robust actor whose credits include Othello and Pushkin’s Boris Godunov. His Aleksandr Vladimirovich is surprisingly libidinous but sufficiently preposterous. Sonya, Maria Berdinskikh, is a gamin. Neither she nor Makovetskiy’s Vanya could credibly run a rural Russian estate.

The elusive affect of this production is not the concentrated bittersweet aura we know as “Chekhov” – and whose aching vacancy is supported by silence, not music. I thought the use of the Hebrew prayer “Kol nidre” (played by a solo trumpet) as a type of theme-song was a miscalculation – it does not invite submissive repetition under the dialogue. Otherwise, I found the production engaging at one or another level at every unforeseen twist and turn.

In Rouben Mamoulian’s 1935 Porgy and Bess, “I got plenty o’ nuttin’” was accompanied by a set of empty rocking chairs moving to and fro in time with Porgy’s song, as were the needles of women sewing. In Tuminas’s Uncle Vanya, pre-recorded musical cues precisely dictate the timing of a spoken phrase. What any of this may have to do with the legacy of Yevgeny Vakhtangov remains a tantalizing question.

Leave a Reply