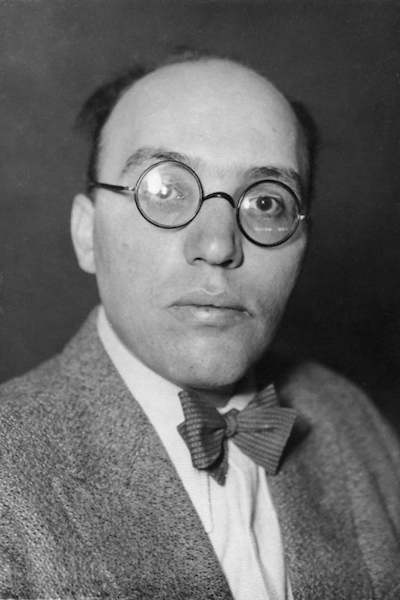

In Berlin 1929 Kurt Weil wrote a “Note Concerning Jazz” which today reads as both a prediction and a warning.

Weill wrote in part:

“Today it appears to me that the manner of performance of jazz is finally breaking through the rigid system of musical practice in our concerts and theaters and that this is more important than its influence on musical composition. Anyone who has ever worked with a good jazz band has been pleasantly surprised by an eagerness, a devotion, a desire for work that one seeks in vain in many concert and theater orchestras.”

Eighty-seven years later, amen to that. Weill continues:

“A good jazz musician completely masters three or four instruments; he plays from memory; he is accustomed to the art of ensemble playing. But above all, he can improvise; he cultivates a free, unrestrained style of playing in which the interpreter achieves to the highest degree a productive performance.”

As I was recently on the West Coast, I had occasion to rent a car for two weeks – and therefore to listen to “classical radio.” Every day I was subjected to recent recordings of familiar music. I quickly discovered a basic similarity in performance style. Never was it “unrestrained.” Never did it achieve “to the highest degree a productive performance.” One rare occasions I encountered a degree of individuality – as in a fresh recording of Beethoven’s E major Sonata, Op. 14, No. 1, rendered by a young pianist of some reputation. But even here there was not a whiff of spontaneity.

Anyone familiar with how recordings are made the studio should be unsurprised. That note-perfect Beethoven E major Sonata had doubtless been spliced. And you can’t splice a performance credibly unless it’s rendered with some regularity, both internally and sequentially via multiple takes.

When I returned to my hotel I resorted to youtube for an antidote and listened to Artur Schnabel’s 1930s version of the same sonata. This, too, is a studio recording – but it predates magnetic tape and was not susceptible to splicing. The first thing I noticed was that Schnabel does not maintain anything like a steady pulse. The tempo of the first movement quickens (often in response to harmonic density) and retards (as does a human pulse). This is not a spliceable performance.

Mainly, however, I noticed the depth and variety of this pianist’s emotional vocabulary – in particular, the unexpected gravitas of the little Allegretto movement. Schnabel’s interpretation here begins with an idea – a state of being. (Wagner once wrote that a conductor’s chief and most elusive responsibility is to extrapolate the “idea” of a piece.) I did not sense anything like that in any of the pristine broadcast recordings I sampled in my rented car.

Here’s a criterion for an “unrestrained” performance – it cannot be spliced. Many piano performances by Edwin Fischer or Albert Cortot are of this kind. There are even pianists who can sound “unrestrained” in magnetic-tape times – say (to cite opposites), Wilhelm Kempff or Vladimir Horowitz.

I was subsequently reminded of Weill’s essay, as predictive rather than admonitory, last weekend in Washington, D.C. PostClassical Ensemble (I’m the Executive Director) presented two days of music performed by David Taylor (bass trombone), Daniel Schnyder (saxophones), Matt Herskowitz (piano), and Min Xiao-fen (pipa). The centerpiece was the world premiere of a jazzy Schnyder Pipa Concerto that deserves the widest possible exposure. Like Schnyder’s music generally, it seamlessly transgresses boundaries of style and genre. It also happens to be a fabulous vehicle for a demonic virtuoso – Xiao-fen – who has mastered a variety of plucked instruments; who improvises; who sings; who cultivates an “unrestrained style of playing.”

Taylor (the world’s most famous bass trombonist) equally exemplifies the “unrestrained.” Last week I twice heard him play the Zuhälterballade from Weill’s Dreigroschenoper. The two performances were so different that you can forget about studios and splicing. The late Gunther Schuller (who crossed over between classical and jazz) (as does Taylor) once called David Taylor “one of the three greatest instrumentalists in the world.” He didn’t say who the other two were. Taylor is great in the ways Weill extolled in 1929.

Schubert’s “Doppelgänger” is a Taylor specialty. I have heard him do it half a dozen times, all different. Here he is with PostClassical Ensemble at the Kennedy Center.

Whenever I visit music schools I make a practice of sharing this youtube performance. The range of reaction is very wide. I must confess that emotional reticence is a frequent keynote – an inability to enter into an uncomfortable realm of feeling. There is too often a predilection to attempt to “classify” Taylor – a fruitless endeavor. I even encounter complaints about his attire.

I discover cheerful versatility and spectacular facility among the young instrumentalists I encounter. What I miss is emotional “unrestraint.” I turn to David Taylor, pushing age 70, for “the highest degree of productive performance.”

Thank you deeply, Joseph, for sharing especially your thoughts … Informative and inspiring… What can be better!!….. James Dick