“Music Unwound” is an orchestral consortium supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. It funds contextualized symphonic programs in collaboration with colleges and universities. To date, two topics have been in play. “Dvorak and America” explores the quest for American cultural identity ca. 1900; the central work is Dvorak’s New World Symphony, supplemented by a “visual presentation” aligning the music with Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha and the canvases of Frederick Church, George Catlin, and Frederic Remington. “Copland and Mexico” explores Aaron Copland’s Mexican epiphany of the 1930s; the central work is the iconic Mexican film Redes (1935), with Silvestre Revueltas’s terrific score performed live.

Music Unwound” is now commencing a second funding cycle with the addition of “Charles Ives’s America” — which debuted in Buffalo three weeks ago and included two Buffalo Philharmonic subscription concerts plus half a dozen ancillary events at a museum, a library, and a university. The central work was Ives’s Symphony No. 2 (1900-1909) – an irresistible Great American Symphony only premiered in 1951 when Leonard Bernstein rescued it from oblivion for a national New York Philharmonic radio audience.

That notwithstanding Bernstein’s impassioned launch, Ives’s Second Symphony never entered the mainstream symphonic repertoire records a discouraging lack of advocacy. It has simply not been performed sufficiently to acquire the audience it deserves. As a result, orchestras resist programming Ives’ Second because it doesn’t sell tickets – a vicious circle perpetuating the stereotype of Ives as a cranky composer of “difficult” music. The “Music Unwound” program – which tells the Ives story with a 30-minute visual track – is a necessary attempt to win audiences over to our most important symphonist.

Central to the presentation was a performance by baritone William Sharp (a peerless singer of Ives) of the hymns and songs that generate Ives’s symphonic motifs. These range from the inane college song “Where Oh Where Are the Verdant Freshmen?”, which Ives whimsically appropriates as a lovely sonata-form second subject, to Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe,” which in Ives’s Civil War finale signifies compassion for the slave.

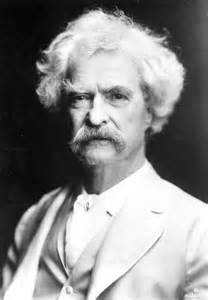

These twin aspects of Ives’s Second Symphony – the exuberance with which it subverts a hallowed European genre with American vernacular strains; the poignancy with which it connects to slavery and race – resonate mightily with Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, which Ernest Hemingway famously called the starting point of American literature. What Huck Finn is to the American novel, Ives’s Second is to the American symphony. And the moral epiphany of Twain’s novel – the scene on the raft in which Huck humbles himself before the human being in Jim – parallels Ives’s compassion for the African-American, a legacy inherited from his Abolitionist grandparents.

Twain’s rambunctious sense of humor, thumbing his nose at European cultural parents with pretended innocence, is also Ivesian – as when in the Second Symphony a Bach fugue must contend with “Camptown Races,” and Stephen Foster comes out on top. (I write about Ives and Mark Twain in the least-known, least-read of my ten books: Moral Fire: Musical Portraits from America’s Fin-de-Siecle.)

The “Music Unwound” Ives program will next be presented by the Pacific Symphony in Spring 2016. William Sharp will again participate. The central university partner will be Chapman University. The possibilities for cross-disciplinary inquiry are limitless.

Some day, Charles Ives – who knew Mark Twain; who identified with the Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau — will take his rightful place in the American cultural pantheon alongside such equally self-made Americans as Twain, Emerson, and Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Hermann Melville. Were Ives a writer or painter, this would have happened long ago. But American cultural historians ignore classical music, and American orchestras remain chronically Eurocentric.

Leave a Reply