Rifftides: March 2009 Archives

Since Rifftides began nearly four years ago, I have posted frequently about Ben Webster - but not frequently enough. That would be impossible. Few improvising  artists have achieved Webster's level of supremacy at speaking their pieces with eloquence and brevity. I would not suggest that eloquence has fled; it is possible to be eloquent at length. But in the post-Coltrane age of solos as tests of endurance it may be unnecessary to point out that succinctness is not one of the guidelines in most jazz playbooks. Webster is an antidote to the ennui induced by long-windedness.

artists have achieved Webster's level of supremacy at speaking their pieces with eloquence and brevity. I would not suggest that eloquence has fled; it is possible to be eloquent at length. But in the post-Coltrane age of solos as tests of endurance it may be unnecessary to point out that succinctness is not one of the guidelines in most jazz playbooks. Webster is an antidote to the ennui induced by long-windedness.

This year is the 100th anniversary of Webster's birth. You may count on my finding every opportunity to call to your attention the art of that incomparable tenor saxophonist. This is a link to a recent piece that addresses a reader's distress with a tenor saxophonist who pays tribute to Webster. It also leads you to video of a heartbreakingly beautiful Webster ballad performance and a series of comments from Rifftides readers. This link takes you to a piece from 2005 in which a woman who is neither a musician nor a critic encapsulates in a sentence the essence of Webster's musical persona.

Here is Webster in two videos that materialized on YouTube just last November. He is with Oscar Peterson, piano; Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, bass; and Tony Inzalaco, drums. The first piece is the blues he called "Poutin'." The second is "Sunday," one of his favorites for decades. This would seem to be early 1970s. Webster died in 1973.

Okay, we've had enough fun with Sue Raney's Scopitone romp in the park. To see it and the comments about it, go here. But first, watch and listen to Ms. Raney sing a Henry Mancini song that has long been one of her signature pieces. This is the sort of thing I had in mind the other day when I used the adjective "divine" in referring to her.

I don't know who the alto saxophone soloist is. He did a lovely job with the bridge.

Old pal Tim Ryan called my attention to an interview Judith Schlesinger, our leading combination jazz writer/psychotherapist, did with guitarist Gene Bertoncini nearly a year ago. The interview ran on the All About Jazz web site, and I missed it last April. Maybe you missed it, too. It is fascinating for its insights into Bertoncini's musical thinking, his quick wit and his interchanges with Dr. Schlesinger. Verbatim transcribed interviews are far from my favorite form of journalism, but when they work, they can be valuable. This one works.

Here is an exchange that grew out of Judith's mention of Bertoncini's study of architecture at Notre Dame. He didn't realize that he and Antonio Carlos Jobim had architecture in common. Throughout, Bertoncini is identified as GB, Dr. Schlesinger as AAJ.

AAJ: In discussing your music, people often speculate about how your architect training informs your playing. There's another great musician who was also into architecture, and that was Jobim.

GB: Really?AAJ: Apparently he was always good at drawing, so when he got married and needed to make some reliable money, he took the entrance exams for architecture school. But he only studied a year before going back to music.

GB: Wow, that's wonderful! I didn't know that. I owe you for this. We met backstage once. Did he ever talk about being influenced by architecture?

AAJ: Not that I know of, but Goethe once said that architecture was "frozen music." What's your take on the connection?

GB: In architecture, you're analyzing a couple of things: artistic balance, balance in design and what constitutes good design, and the needs of people. When designing a structure of any kind you have to be concerned about what's going to be happening inside the structure, and how it's going to make life better for the people in it, whether in a residential or commercial situation. And that opens up all kinds of sensitivities in you. This awareness can easily translate into your music: it becomes a

combination of satisfying yourself and being concerned with the needs of the listener.

I'm always thinking about how my music will affect people--I can't wait to play this for somebody, because I think it's going to make them feel good. Then there's the idea of making a presentation, because an architect always has to present a completed concept for a client. The whole concept is there on paper. I believe very much that this has influenced my sense of arranging: I present a concept for each tune I play, pretty much, that I've thought about. There's a beginning and ending and a middle; there's balance, you know, in a harmonic sense, and in a linear sense, like looking at the elevation of a building.

That's one of the reasons why I work out a lot of things on the guitar. It's not just learning the notes, or how to improvise, it's working out arrangements to improvise from. There are things I just play off the top of my head, but for the most part, I want to have a really great concept for each thing I play.

To read the entire long interview, go here. To hear samples of Bertoncini's splendid duo guitar CD with Roni Ben-Hur, click here.

Marc Myers, the proprietor of the blog called JazzWax, audited one of the polymath Mr. Kirchner's classes at the New School and filed a report that begins:

Bill's two-hour class took his 40 students through Miles Davis' bio and recordings, complete with 13 prime audio examples. The sound system in the New School's fifth floor "performance space" is sensational. Each digital recording was vivid and exciting and rich with warm sonic detail. In between tracks, Bill filled in the blanks with authoritative notes:

Marc's piece includes Kirchner's list of recordings used in the class and appends video of a latterday Davis performance when Miles was well into his electronic period. To see his report, click here. I'm not ready to agree that Davis's performance is a work of art, particularly in comparison with the other tracks on Bill's list, but it is worth seeing and hearing. Once.

If you missed the saga that began with Kirchner's list of big band recordings since 1955, see the Rifftides exhibit two below this one. It will link you to the previous installments.

I would go to the library and borrow scores by all those great composers, like Stravinsky, Alban Berg, Prokofiev. I wanted to see what was going on in all of music. Knowledge is freedom and ignorance is slavery, and I just couldn't believe someone could be that close to freedom and not take advantage of it.

It was because of Bill [Evans]'s influence, I think, that I always had classical music on around the house. It was so soothing to think and work by. I mean people would come by and expect to hear a lot of jazz on the box, but I wasn't into that at the time and a lot of people were shocked to hear me listening to classical music all the time, you know, Stravinsky, Arturo Michelangeli, Rachmaninoff, Isaac Stern.

I don't like to hear someone put down dixieland. Those people who say there's no music but bop are just stupid; it shows how much they don't know.

You cant play nothing on modern trumpet that doesn't come from him, (Louis Armstrong) not even modern shit. I can't even remember a time when he sounded bad playing the trumpet. Never. Not even one time. He had great feeling up in his playing and he always played on the beat. I just loved the way he played and sang.

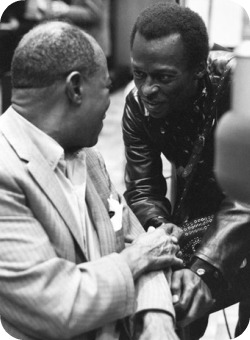

Photo © Jamie Parslow, 1970

Bill Kirchner started this big band discussion on March 20 with a list of recordings recommended to his advanced composing and arranging students in New York. He drew some praise and some scattered fire from Rifftides readers, most of which appears in the exhibit two below this one. Mr. Kirchner requested the right of reply. The Rifftides staff is happy to grant it.

All interesting comments, some of which require nothing additional from me, though some do. First, a general comment: my list was compiled so that students could obtain some great recordings at reasonable prices. (Most of the CDs on the list can be had for under $10. That leaves out some collector's items.)To Ted O'Reilly and Barak: the Stan Getz Change of Scenes album I mentioned (with the Clarke-Boland Big Band) contains what is by far the most adventurous and stimulating writing I've ever heard by Francy Boland. As for Gerald Wilson, his album that I would have included, Moment of Truth, is listed on Amazon.com for $95-way beyond the budgets of most students.

To Ed Leimbacher: call me pertinacious, but I've never found Neal Hefti's writing on The Atomic Basie, good and memorable as it is, as compelling as that by Frank Foster, Thad Jones, Frank Wess, Ernie Wilkins, and Billy Byers on the three albums I mentioned. As for the Verve Jazz Masters 36 and 48, they are anthologies (the only ones currently available, to my knowledge) of Gerry Mulligan Concert Jazz Band and Oliver Nelson big band music, respectively. (Full disclosure: I did liner notes for both CDs and picked the selections for the former.)

To John Shade and Mark Stryker: I wish I could be more enthusiastic about Toshiko Akiyoshi's writing, but with occasional exceptions (I included "Sumie" in the now-out-of-print Smithsonian Big Band Renaissance boxed set), I cannot. The late Rayburn Wright, one of the greatest composing-arranging teachers, once described her writing to me as follows: "It makes sense horizontally but not vertically." Her bands were consistently excellent, though.

To Richard Mathias: Gary McFarland is one of my biggest influences as a composer-arranger. Alas, Profiles is one of those too numerous McFarland recordings that has never made it to CD (and which in any case contains only about half of the music from that 1966 concert). The October Suite (which, thank God, was finally reissued on CD a few years ago and is still available) is one of my desert-island records. Steve Kuhn graciously allowed me to xerox the scores, which I use in my teaching.

To Jim Brown: I merely said that Bill Holman's charts on the Kenton Contemporary Concepts album represent his very best work, and a great introduction to it for students. But I wouldn't presume to say that he has done nothing as good since the early '60s; I don't believe that for a moment.

To Mark Stryker: Slide Hampton IS on the list-sort of. There are several splendid charts by him on the Joe Henderson Big Band album I listed. And like you, I've enjoyed Braxton's Creative Orchestra Music 1976 --though in that vein I prefer Muhal Richard Abrams' writing to Braxton's.

To Dave Frishberg: You're a world-class musician who deserves much respect. The Ellington/Strayhorn Nutcracker is a nice record that I enjoy on occasion. But to me, it has little of the musical and emotional depth of The Far East Suite, ...and His Mother Called Him Bill, and countless other Ellington albums. P.S. : I "get" Mingus. And Coltrane. Does that make me a bad person in your eyes?

New comments have shown up. I have attached them to the March 20 and March 23 items and will post others as they arrive. Now, Rifftides will move on to other matters.

When I was researching last month's entry about Paul Desmond and the Scopitone, I encountered a film that seemed so unlikely, I set it aside to share with you later and only now remembered it. The divine Sue Raney, it turns out, was a Scopitone artist. I doubt that this song survives in her repertoire, but it certainly fit Scopitone's '60s European mod ethos.

Bill Kirchner's list of recommended big band albums, compiled for his students, brought reaction. As might have been predicted, knowledgeable and opinionated Rifftides readers sent in their comments. Here they are. If more come in, we will compile and post them. Thanks to everyone who responded.

Very nice list. I am glad to see some names included (Don Ellis, Claire Fischer) that others might leave off. I hope your students dig into the music you are suggesting. Of course, I can't help mentioning a few of my favorite big band CDs from the period for possible inclusion:

Terry Gibbs: Terry Gibbs Dream Band.

Vince Mendoza: Blauklang (a real sleeper here, and not widely heard since it is on a European label).

Bob Curnow's L.A. Big Band: The Music of Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays

Dave Holland Big Band: What Goes Around.And I just got a copy of a (still to be released) CD earlier this week that knocks my socks off . . Vipassana: Numinous Plays the Music of Joseph C. Phillips, Jr. Imagine Steve Reich collaborating with Maria Schneider . . . If you get a chance to hear it, check it out. - Ted Gioia

Nice list, though I might drop a couple, and add something from both the Clarke/Boland Big Band, and Rob McConnell's Boss Brass. - Ted O'Reilly

Bill K.'s list pretty much nails it. I would also suggest JJ Johnson's Brass Orchestra on Verve (1997). Architecturally ambitious, rich in color (no reed section), stylistically comprehensive, and swinging. JJ's compositions and arrangements mostly ("Enigma," "El Camino Real," etc.) but also arrangements by Slide Hampton, Robert Farnon, Robin Eubanks; and "Swing Spring," "Gingerbread Boy," and "Wild Is The Wind." Long out of print on the CD side, Amazon lists a few copies from its affiliated sellers ($7.15!!) and iTunes has it as well. I'd go for the CD: the booklet is superb and you get notes and a full personnel listing. Full disclosure: I greenlighted the project during my term at Verve. It was probably the biggest money-loser we had, and it was one of the best decisions I ever made. I miss JJ. - Chuck Mitchell

Seems to me slightly pertinacious to recommend the Basie items listed but then omit the so-called Atomic Basie album on Roulette, often considered the highwater mark of his Fifties band. And what the heck are the Verve Master CDs doing there; do they represent actual albums reissued without name? Or are they anthologies (as would seem)? Also, I would nominate the lovely Laurent Cugny albums dedicated to Gil Evans' works (and including his participation in small ways) as worthy end-of-life tributes to a real Master; it would be interesting to know what Maria Schneider, Gil's assistant and protege, thinks of them. - Ed Leimbacher

How about something by Toshiko Akiyoshi: Kogun, perhaps, or Long Yellow Road? They seem to me to be both original, with their synthesis of East and West, and powerful. - John Shade

As a high school student in the mid 60's (grad 1967) and a saxophone/jazz arranger nerd, I wore out several copies of Woody Herman's '63 and '64 albums along with This Time By Count Basie: Hits of the 50's and 60's. My friends were into the Kenton Band, which, other than the live Neophonic Orchestra album, bored me. Don Ellis was big too. I did get swept into this for a while.The local Wallgreens Drug Store had a "cut out bin" with jazz albums that sold for $1.00. Gary McFarland's Profiles entered my life. It was the most creative writing I had heard. Innovative yet unpretentious use of altered big band instrumentation. What would normally be the standard trombone section has Bob Brookmeyer on valve bone, Jimmy Cleveland, Bob Northern on French horn, and Jay McAllister on tuba. The reed section is stacked with a mix of the the best doublers and improvisers in New York at the time. Phil Woods, Jerry Dodgion, Zoot Sims, Richie Kamuca, and Jerome Richardson. We get Gabor Szabo AND Sam Brown on guitar (Gabor gets to be Gabor) plus Richard Davis on bass.

My sax player friends were all claiming to be learning "Giant Steps." I transcribed McFarland's "Winter Colors" for the school jazz band. A short time later I got a copy of Gary McFarland's October Suite featuring Steve Kuhn on piano. These two albums turned me into a college composition major. - Richard Mathias

Without nominating a specific example, I'd like to see something from the subgenre of bands that play charts based on recorded solos, like the Monk Town Hall big band and Supersax. Besides "I like it," I think these bands represent a step in the process by which bebop turned into a musical canon, with acknowledged classics--Bird's solo on "Embraceable You" or Monk's on "Little Rootie Tootie." - John Burke

Bill Holman's album Brilliant Corners (his arrangements of Monk's tunes) belongs in every "best of" list, imho. I wish there was a mention of Gerald Wilson and the Clarke-Boland Big Band. - Barak

(Bill Kirchner included Clarke-Boland in his Stan Getz category - DR)

I fully concur with Kirchner's comments re: Holman's earliest work being his best. As much as I love his writing, and I'll go to hear it at every opportunity, I've never heard anything written after the early 60s that approached what he did before then. - Jim Brown

Interesting list that, obviously, touches lots of bases. One immediate addition ought to be Anthony Braxton's Creative Music Orchestra 1976 (Arista/Mosaic). I've always considered it Braxton's definitive record for the way it reconiles his unique take on the tradition with experimentalism. The album includes two jagged yet groovy stompos with culicue saxohone lines and puncy brass that comes out of Ellington, et. all, but there's also a remarkably wild march that connects the dots between Sousa, Ives, post-Webern classical modernism and the jazz avant-garde -- quintessential Braxton. A few other possibilities that come to mind off the top:

Gunther Schuller's writing for either of the two albums with Joe Lovano, Rush Hour and Streams of Expression (both Blue Note), bring his Third Stream ideas up to date in very satisfying ways.I'd like to figure out a way to get Slide Hampton on the list -- probably The Way by the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra (Planet Arts), which features all Hampton charts. Toshiko Akiyoshi's band ought to be on the list too. The great early RCA LPs from the mid '70s are now out as a Mosaic Select box, but if I had to pick just one, it would be Long Yellow Road. - Mark Stryker

I saw Bill Kirchner's list of commendable big band albums since 1955, and I think he's left out the one album that stands out far above anything on the list, and that's The Nutcracker Suite by Ellington/Strayhorn on Columbia c.1961. As I see it, this is the most intelligent, most resourceful, most imaginative, musically impeccable, and wittiest composing and arranging for big band that's ever been heard in jazz. And the band's performance is electrifying. How does one leave this out--and include two Charles Mingus albums? I don't get it. But hey, I never got Coltrane either. Or Elvis. Sue me. - Dave Frishberg

Bruno Leicht writes from Germany, embedding a weekend viewing and listening present.

Browsing YouTube can be an adventure. Never seen this film before. Louis Armstrong and the All Stars at Newport, 1958. -- Please listen and look closely. Miles was wrong; Pops was no Uncle Tom. This man WAS serious, nothing else but a super-professional artist here. Just watch him play his trumpet, look at his face when he announces the last number: Absolutely no traces of "Uncle Tom", except the joy of performing some funny lyrics of Rockin' Chair with a surprise guest.

Pops was a man of jazz: Deep, concerned and totally focussed on the music, on the people he performed with, and on the audiences he played for. His sound is so clear and strong here, I'm completely overwhelmed.Especially on minute 2:26 is a particularly brilliant phrase, two glissandi in a break, perfectly timed ... can't describe them ... It's amazing how he does that. Pure genius to me. No one else could do such little big things as convincingly as Louis Armstrong.

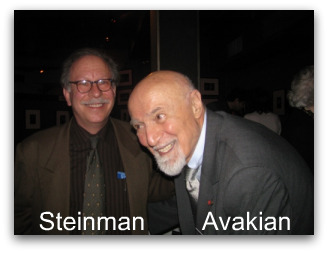

George Avakian has produced recordings by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Erroll Garner, Sonny Rollins, Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond, among others. With the 78 rpm albums of Armstrong's Hot Fives and Hot Sevens that he oversaw for Columbia Records in the 1940s, he invented the jazz reissue.

George turned 90 this week, and there was a huge party for him at Birdland in New York City. A wide cross-section of the jazz community turned out for the celebration. A splendid ad hoc mainstream band signed on to honor Mr. Avakian. They were David Ostwald, tuba; Randy Sandke, trumpet; Wycliffe Gordon, trombone and vocals; Anat Cohen, clarinet; Mark Shane, piano and vocals; Kevin Dorn, drums. Michael Steinman, proprietor of the excellent Jazz Lives web site, was there to report on the party.

Steinman's report includes four videos of the band playing and one of George, with his customary charm, addressing the celebrants. To see it, click here.

Steinman's report includes four videos of the band playing and one of George, with his customary charm, addressing the celebrants. To see it, click here.

Happy Birthday, George.

Among the French impressionist composers who intrigued jazz musicians as early as the 1920s was Erik Satie. His Gymnopédies for piano were particular favorites. In later years, some jazz players, including Bill Evans and Herbie Mann, adopted them into their own repertoires. Satie's Gnossiennes may not be as familiar as the Gymnopédies, but they have qualities of their own and are no less captivating. Here is Alexandre Tharaud playing the Gnossienne no. 1. The video production includes scenes of the pianist's hands disembodied and the piano being tuned, enigmatic touches that seem somehow appropriate to the mysterious personality of the composer.

Spring is here and my Italian friend Vigorelli Bianchi took me for our first ride of 2009. It was blustery and the sun was only occasionally peering between cloud banks, but we had a great time. Stamina was okay. The legs need conditioning. I stopped to speak with a fellow cyclist who was repairing a tube done in by a goathead thorn. I mentioned how good it felt to finally be out after weeks of unusual cold.

a great time. Stamina was okay. The legs need conditioning. I stopped to speak with a fellow cyclist who was repairing a tube done in by a goathead thorn. I mentioned how good it felt to finally be out after weeks of unusual cold.

"I've done 500 miles this year," he said.

Oh.

For his advanced composing and arranging students, saxophonist, composer, arranger and educator Bill Kirchner recently compiled a list of recommended big band CDs recorded since 1955. Kirchner teaches at The New School and Manhattan School of Music in New York City and New Jersey City University. Bill agreed to let me share the list with Rifftides readers, who may find some of their favorites but not others.

For his advanced composing and arranging students, saxophonist, composer, arranger and educator Bill Kirchner recently compiled a list of recommended big band CDs recorded since 1955. Kirchner teaches at The New School and Manhattan School of Music in New York City and New Jersey City University. Bill agreed to let me share the list with Rifftides readers, who may find some of their favorites but not others.

RECOMMENDED BIG BAND CDs, 1955-PRESENT--Bill Kirchner

Muhal Richard Abrams: The Hearinga Suite (Black Saint)Count Basie: April in Paris, Frankly Basie (both Verve), Chairman of the Board (Roulette)

Carla Bley: Big Band Theory (Watt)

Bob Brookmeyer: New Works--Celebration (Challenge)

Miles Davis-Gil Evans: Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, Sketches of Spain (all Columbia)

Duke Ellington: The Far East Suite, ...and His Mother Called Him Bill (both RCA/Bluebird)

Don Ellis: Tears of Joy (Columbia/Wounded Bird)

Gil Evans: The Complete Pacific Jazz Sessions (Blue Note), The Individualism of Gil Evans (Verve)

Clare Fischer: Thesaurus (Atlantic/Koch)

Stan Getz: Big Band Bossa Nova (arr. Gary McFarland), Change of Scenes (w/ the Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band) (both Verve)

Joe Henderson: Joe Henderson Big Band (Verve)

Woody Herman: Giant Steps (Fantasy/Original Jazz Classics)

Thad Jones-Mel Lewis: Consummation (Blue Note)

Stan Kenton: Contemporary Concepts (Capitol)

Joe Lovano (with the WDR Big Band arr. by Mike Abene): Symphonica (Blue Note)

Charles Mingus: Let My Children Hear Music (Columbia)

Mingus Big Band: The Essential Mingus Big Band (Dreyfus)

Gerry Mulligan: Verve Jazz Masters 36 (Verve)

Oliver Nelson: Verve Jazz Masters 48 (Verve)

Buddy Rich: The New One, Mercy, Mercy (both Pacific Jazz)

Maria Schneider: Evanescence (Enja)

Vanguard Jazz Orchestra: Up From the Skies (arr. Jim McNeely), Monday Night Live at the Village Vanguard (both Planet Arts)

Kenny Wheeler: Music for Large and Small Ensembles (ECM)

I suggested to Kirchner that, despite Bill Holman's splendid work on the Kenton Contemporary Concepts album, one of Holman's own CDs should be on the list. He replied,

As much as I respect what he's done on his own, I think that the Kenton CC album shows him at his very best--and is for students the best introduction to Holman's work. (In the same way that Stravinsky did great things all during his career, but never wrote anything "better" than The Rite of Spring.)

If you submit a suggested addition to Bill's list, kindly give a musical justification. For our purposes, "I like it" is not justification. Please use the Comments link at the end of the item. When we receive enough replies, we'll post a followup.

I have written here from time to time about the harm the United States has done itself by failing in recent years to practice the cultural diplomacy that did it so much good for decades following World War II. After the Berlin Wall fell and European communist totalitarianism followed, the Clinton administration dismantled the United States Information Agency. The USIA's functions, we were told, would be taken on by the State Department, but State has done little with them during a period when the US has been in crucial need of international good will. The Bush administration began taking down the Voice of America. It appears that the VOA has little chance of regaining its extensive international outreach which, of course, included a major component of jazz broadcasting.

When people the world over want to learn French, they typically go to thelocal Alliance Française, a French language and culture center run by the government of France. To explore Germany's rich culture and take some German classes, they might stop by one of the German government's Goethe-Instituts. But for English, where do they go? They usually head to an outpost of the British Council, not to a U.S.-sponsored cultural center.

Why? Because nearly all of the popular "American Centers" that spanned the globe, attracting throngs of students and young people who immersed themselves in American publications and ideas, have been closed or drastically downsized and restructured thanks to policy decisions, security concerns, and budget constraints. The unintended result is that in the global contest for ideas, the United States is playing short-handed.

Lugar argues that despite security concerns and tight funds in economic hard times, new versions of those centers should be created.

The United States should not abandon this part of the public diplomacy field to others. Iran, for instance, has opened some 60 Iranian cultural centers in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe that offer Persian language courses and extensive library resources-and a platform for anti-American propaganda.As part of a broader overhaul of its public diplomacy effort, the United States should reinvigorate the old American Centers concept-putting, when possible, new ones that are safe but accessible in vibrant downtown areas-support active cultural programming, and resume the teaching of English by American or U.S.-trained teachers hired directly by embassies. That would help draw people to the centers and ensure that students got some American perspective along with their grammar.

What Senator Lugar recommends would be one element of a revitalized US cultural diplomacy policy, a good beginning. To read all of his article and an assortment of opinions about it from Foreign Policy readers, follow this link. Your comments are always welcome here. Please also send them to your senators and congressmen and to the White House.

Charles Tolliver, Emperor March (Half Note). Tolliver received considerable attention for his part in the recent observance of the 50th anniversary of Thelonious Monk's Town Hall concert. Here, we have Tolliver's big band playing his own music. As in the 2007 With Love CD that announced the trumpeter and composer's resurgence, Tolliver melds new departures with traditional values that include dynamite writing for brass. His solos and those by veterans Stanley Cowell, piano, and Billy Harper, tenor saxophone, are superb. Among the youngsters who emerge impressively from the sections are pianist Anthony Wonsey, trombonist Mike Dease and tenor saxophonist Marcus Strickland. "In The Trenches" is an expansion of an audacious blues the composer developed 20 years or so ago. The first and final passages of Tolliver's title tune, inspired by the film March of the Penguins, has riff-like qualities that could embed it in the public consciousness - if the public were to again became conscious of jazz.

Charles Tolliver, Emperor March (Half Note). Tolliver received considerable attention for his part in the recent observance of the 50th anniversary of Thelonious Monk's Town Hall concert. Here, we have Tolliver's big band playing his own music. As in the 2007 With Love CD that announced the trumpeter and composer's resurgence, Tolliver melds new departures with traditional values that include dynamite writing for brass. His solos and those by veterans Stanley Cowell, piano, and Billy Harper, tenor saxophone, are superb. Among the youngsters who emerge impressively from the sections are pianist Anthony Wonsey, trombonist Mike Dease and tenor saxophonist Marcus Strickland. "In The Trenches" is an expansion of an audacious blues the composer developed 20 years or so ago. The first and final passages of Tolliver's title tune, inspired by the film March of the Penguins, has riff-like qualities that could embed it in the public consciousness - if the public were to again became conscious of jazz.

Seamus Blake, Live In Italy (Jazz Eyes). Except for the use of electronics as, er,

enhancement in the opening track and wry punctuation in the last, this is an acoustic set. The New York tenor saxophonist out of Canada by way of Berklee affirms that he is one of the most consistently interesting soloists of his generation. Blake Is accompanied by stalwart contemporaries Danton Boller on bass and Rodney Green on drums, with the veteran pianist David Kikoski. Affinity among the group is notable on Blake's "Way Out Willy" and an extended "Darn That Dream" that begins with a ravishing Blake cadenza. A long invention based on the second movement of Debussy's string quartet objectifies the harmonic inspiration the impressionist master has long supplied jazz musicians. The journeyman Kikoski's long presence as a reliable component of the New York scene does not mean that he should be taken for granted. Nor does his work here allow him to be. Live recording quality is exceptional.

Jaki Byard, Sunshine Of My Soul: Live At The Keystone Korner (High Note). Not to be confused with the late pianist's 1967 trio album also called Sunshine Of My Soul, this is Byard at the lamented San Francisco club in a 1978 solo recording unreleased until 2007. Unclassifiable and irrepressible, he roars through more than an hour of stride, boogie woogie, bebop, interpretations of Mingus, transfigured pop songs, tone poems and a tour de force on one of his favorites, "Besame Mucho." He includes his "Sunshine," a swirling adventure in command of the piano and control of time. That piece is also on the other Sunshine Of My Soul with Elvin Jones on drums and David Ienzon on bass. Any Byard lover needs it, too.

Jaki Byard, Sunshine Of My Soul: Live At The Keystone Korner (High Note). Not to be confused with the late pianist's 1967 trio album also called Sunshine Of My Soul, this is Byard at the lamented San Francisco club in a 1978 solo recording unreleased until 2007. Unclassifiable and irrepressible, he roars through more than an hour of stride, boogie woogie, bebop, interpretations of Mingus, transfigured pop songs, tone poems and a tour de force on one of his favorites, "Besame Mucho." He includes his "Sunshine," a swirling adventure in command of the piano and control of time. That piece is also on the other Sunshine Of My Soul with Elvin Jones on drums and David Ienzon on bass. Any Byard lover needs it, too.

You may recall the Rifftides tip a year ago about a Michel Petrucciani documentary DVD. The film followed the pianist around the world and culminated in a memorable concert shortly before he died in 1999. If you didn't know about Petrucciani before you saw the film, it is unlikely that you forgot him afterward.

In the current issue of The New Republic, David Hajdu does a fine job of placing Petrucciani in his time, assessing the importance of his music and tracing his refusal to let disability impede his art. Petrucianni's osteogenesis imperfecta, the "glass bones" disease, stopped his growth at three feet and impaired his mobility. It never overcame his spirit. Here are excerpts from the early part of Hajdu's piece.

I cannot think of a jazz pianist since Petrucciani who plays with such exuberance and unashamed joy. Marcus Roberts and Michel Camilo have greater technique; Bill Charlap and Eric Reed, better control; Fred Hersch has broader emotional range; Uri Caine is more adventurous. Their music provides a wealth of rewards--but not the simple pleasure of Michel Petrucciani's. With the whole business of jazz so tentative today, you would think more musicians would express some of Petrucciani's happiness to be alive.

Giddily free as an improviser, Petrucciani trusted his impulses. If he liked the sound of a note, he would drop a melody suddenly and just repeat that one note dozens of times. His music is enveloping: he lost himself in it, and it feels like a private place where strange things can safely ensue. Today, when so much jazz can sound cold and schematic, Petrucciani's music reminds us of the eloquence of unchecked emotion.

Hajdu's article, "The Keys to the Kingdom," is on The New Republic's web site. To read the whole thing, click here.

Here is Petrucciani in Germany in 1993. YouTube identifies what he plays as "C-Jam Blues." It is, except when it's Monk's "I Mean You."

If you detect similarities between Petrucciani and the pianist in the next exhibit, don't let it bother you.

I am adding to Other Places in the right column a link to Mule Walk And Jazz Talk, a web log posted from Madrid by Agustín Pérez. The legend Sr. Pérez erects below the name of his blog leaves no doubt en el que viene de, as they say in downtown Madrid.

Random thoughts, casual writings and specific research on early jazz styles. If you think there is no jazz before Coltrane, you may have come to the wrong place.

Mule Walk And Jazz Talk is bilingual and nicely organized. It is packed with treats, written and visual. Associated with a video clip of Dick Wellstood playing James P. Johnson's "Caprice Rag," for example, is this quote from Wellstood.

I would like to say, first, that I don't like the term "stride" any more than I like the term "jazz". When I was a kid the old-timers used to call stride piano "shout piano", an agreeably expressive description, and when once I mentioned stride to Eubie Blake, he replied, "My God, what won't they call ragtime next?" Terms, terms. Terms make music into a bundle of objects - a box of stride, a pound of Baroque -. [Donald] Lambert played music, not "stride", just as Bach wrote music, not "Baroque". Musicians make music, which critics later label, as if to fit it into so many jelly jars. Bastards.

To a three-part transcribed interview from 1952 with the stride (or shout) pianist Joe Turner, Sr. Pérez appends three video clips of Turner in action on French television in the 1960s. I am shamelessly appropriating one clip. But, then, Sr. Pérez appropriated all of them from Dailymotion. In this one, Turner plays his own "Cloud Fifteen," charmingly, then James P.'s "Carolina Shout, too fast for complete coherency. Still, it is a rare opportunity to see a pianist who deserved wider fame and a plaque from the cigar industry.

The SF Jazz Collective rolls into town next week to play at the world class nonprofit performance hall we have here in an acoustically blessed former church. The local newspaper asked me to write an advancer.

YAKIMA, Wash. -- For a few weeks each year, seven of the busiest musicians in jazz suspend their leadership roles and come together as the SFJazz Collective. Their 2009 tour will bring them to The Seasons on Wednesday.According to alto saxophonist Miguel Zenon, the band is having a great time.

"It's a lot easier," the Yakima favorite said, "when you start getting into the music and don't have to worry about making mistakes and being stressed about playing the parts right. Then it just gets easier and turns into fun. We're now starting to get to that point of this tour."

Zenon, who has played The Seasons twice with his quartet, was calling just before a sound check for the Collective's concert in Albany, N.Y. He has been a member of the SFJC since its founding. His colleagues in the septet are tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, trumpeter Dave Douglas, trombonist Robin Eubanks, pianist Rene Rosnes, bassist Matt Penman and drummer Eric Harland.

To read the whole thing and see a photo of the band, go here. If you're in the neighborhood, see you at the concert. I'll be the guy giving a very short introduction. Be sure to come up and say hello.

The recession seems to be doing little to stem the flood of CDs. This posting and others to follow constitute one man's attempt to deal with the rising tide. The quick hits below are not full-fledged reviews, far from it. They are acknowledgements of a few releases worth investigating. Many of them, no doubt, deserve full analysis. The Rifftides staff regrets that we cannot provide deep consideration of all recordings of merit--or demerit. Listening and writing are linear activities, and the clock keeps ticking. Doomed never to catch up, we're trying to stay abreast of the infinite surge of new recordings.

Geoffrey Keezer, Áurea (ArtistShare). Pianist Keezer is in the thick of the Peruvian movement that is attracting more and more jazz musicians. His playing, compositions and arrangements radiate authenticity and the freshness of Afro-Peruvian jazz. With propulsion by percussionists Hugo Alcázar and Jon Wikan and bassist Essiet Okon Essiet, Keezer crafts inventions based on shifting rhythms and deep harmonies. His colleagues include saxophonists Steve Wilson and Ron Blake, guitarists Peter Sprague and Mike Moreno, and the gifted Argentinian vocalist Sofia Rei Koutsovitis. Keezer's setting of Eduardo Falú's and Jaime Dávalos' "La Nostalgiosa" is profoundly moving. He equals it with his own "Miraflores."

Geoffrey Keezer, Áurea (ArtistShare). Pianist Keezer is in the thick of the Peruvian movement that is attracting more and more jazz musicians. His playing, compositions and arrangements radiate authenticity and the freshness of Afro-Peruvian jazz. With propulsion by percussionists Hugo Alcázar and Jon Wikan and bassist Essiet Okon Essiet, Keezer crafts inventions based on shifting rhythms and deep harmonies. His colleagues include saxophonists Steve Wilson and Ron Blake, guitarists Peter Sprague and Mike Moreno, and the gifted Argentinian vocalist Sofia Rei Koutsovitis. Keezer's setting of Eduardo Falú's and Jaime Dávalos' "La Nostalgiosa" is profoundly moving. He equals it with his own "Miraflores."

Fat Cat Big Band, Meditations on the War for Whose Great God is the Most High You are God (Smalls). Angels Praying (Smalls). The bizarre cover illustration and the title mantra of the Meditations CD steeled me for an outpouring of anger, new age rumination, avant garde self-indulgence or, possibly, all of that. Instead, in both albums we hear an 11-piece ensemble of good young New York players cruising the modern mainstream and soloing well. The compositions and arrangements by guitarist and leader Jade Synstelien are tinged with Mingus, Ellington and possibly a hint of Gary McFarland. I finally got to hear trumpeter Tatum Greenblatt, and understood why established trumpet soloists like Jay Thomas are talking about him. Synstelien's vocals in a style reminiscent of Frank Zappa would fit the Industrial Jazz Group or Reptet. In this context, they come as a bit of a jolt. Maybe that's what he intended.

Meditations CD steeled me for an outpouring of anger, new age rumination, avant garde self-indulgence or, possibly, all of that. Instead, in both albums we hear an 11-piece ensemble of good young New York players cruising the modern mainstream and soloing well. The compositions and arrangements by guitarist and leader Jade Synstelien are tinged with Mingus, Ellington and possibly a hint of Gary McFarland. I finally got to hear trumpeter Tatum Greenblatt, and understood why established trumpet soloists like Jay Thomas are talking about him. Synstelien's vocals in a style reminiscent of Frank Zappa would fit the Industrial Jazz Group or Reptet. In this context, they come as a bit of a jolt. Maybe that's what he intended.

Joe Temperley, The Sinatra Songbook (Hep). Yet another Sinatra tribute? Yes, please. Temperley, the baritone sax anchor and soprano saxophonist of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, plays standards from Sinatra's repertoire. The only original is "Moontune," composed by guitarist James Chirillo on the framework of "Fly Me to the Moon" with a jaunty out-chorus for the octet. Temperley's LCJO colleagues trumpeter Ryan Kisor and pianist Dan Nimmer and five other state-of-the-art musicians are aboard. Everybody gets plenty of solo time, but Temperley is the central figure. His caressing of "Nancy" on the big horn is a highlight. Everything Nimmer plays is a highlight.

Joe Temperley, The Sinatra Songbook (Hep). Yet another Sinatra tribute? Yes, please. Temperley, the baritone sax anchor and soprano saxophonist of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, plays standards from Sinatra's repertoire. The only original is "Moontune," composed by guitarist James Chirillo on the framework of "Fly Me to the Moon" with a jaunty out-chorus for the octet. Temperley's LCJO colleagues trumpeter Ryan Kisor and pianist Dan Nimmer and five other state-of-the-art musicians are aboard. Everybody gets plenty of solo time, but Temperley is the central figure. His caressing of "Nancy" on the big horn is a highlight. Everything Nimmer plays is a highlight.

Bill Henderson, Beautiful Memory: Live At The Vic (Ahuh). Henderson is a few days short of his 83rd birthday. Only 81 when this was recorded, he was as vigorous, rhythmically assured, in tune and full of blues and bop essences as when I first heard him singing as a stripling of 36. Embracing a sophisticated ballad ("Sleepin' Bee"), updating a traditional classic ("Royal Garden Blues") or improving on Elton John ("Sorry Seems to be the Hardest Word"), Henderson is utterly convincing.

birthday. Only 81 when this was recorded, he was as vigorous, rhythmically assured, in tune and full of blues and bop essences as when I first heard him singing as a stripling of 36. Embracing a sophisticated ballad ("Sleepin' Bee"), updating a traditional classic ("Royal Garden Blues") or improving on Elton John ("Sorry Seems to be the Hardest Word"), Henderson is utterly convincing.

In today's Wall Street Journal, I write about Denny Zeitlin. The piece is pegged to the simultaneous releases of his new trio CD on the Sunnyside label and a Mosaic box set with nearly all of Zeitlin's Columbia trio recordings. The article begins:

In today's Wall Street Journal, I write about Denny Zeitlin. The piece is pegged to the simultaneous releases of his new trio CD on the Sunnyside label and a Mosaic box set with nearly all of Zeitlin's Columbia trio recordings. The article begins:

In October 1963, a 25-year-old Johns Hopkins medical student sat at a concert grand piano in the East 30th Street studio of Columbia Records in New York and played a masterpiece of a jazz solo. Denny Zeitlin, from a Chicago family devoted to medicine and music, had come to New York for a 10-week fellowship in psychiatry at Columbia University. But the medical student, a pianist since the age of 2 and a professional musician during his high-school years, had also found time during his New York sojourn to study with the seminal composer George Russell, who became one of his champions, and to sit in with some of the city's leading jazz players.

It goes on to tell the story of Dr. Zeitlin's extraordinary life-long equal commitments to music and medicine, which...

... are not enough to absorb Dr. Zeitlin's curiosity and energy. Tall, bearded, lean as a figure in an El Greco painting, he is also devoted to mountain biking, fishing, gastronomy and wine. Nor does he dabble in those interests. As with music and psychiatry, he pursues them.

To read the whole thing, click here, or pick up a copy of the Journal at your doorstep or the nearest news stand.

Music was probably born of the natural rhythms of life. So it shouldn't come as a surprise when people who dedicate themselves to life science release their creative energy in music. - Karen Schmidt in the journal Yale Medicine, 1998

...music is my heritage, I cannot help it - Albert Schweitzer

I gave up my position of professor in the University of Strausbourg, my literary work, and my organ playing, in order to go as a doctor to equatorial Africa -Albert Schweitzer, The Primeval Forest

Regarding Lou Levy's Lunarcy CD reviewed on March 5 (scroll down), a Rifftides reader who identifies himself as Fergus wrote:

You might ask Universal why Lunarcy isn't available on iTunes in the US as it is elsewhere.

The Rifftides staff passed that suggestion on to Universal publicist Regina Joskow. She said that she, in turn, would relay it to the appropriate folks at the record company. I added a suggestion that Universal, which encompasses Verve, also reissue the Levy CD. Ms. Joskow's reply encapsulates the dilemma that faces record companies and, therefore, listeners unable or unwilling to substitute digital downloads for compact discs.

As you can imagine, it becomes far more challenging to release something physically as there are minimum quantities that have to be manufactured. Sadly, fewer and fewer music retailers exist, ESPECIALLY ones that care about jazz. The demise of Tower Records was a huge blow to the jazz industry as it accounted for such a huge portion of our business. Now that Circuit City is gone and Virgin is on its way out, things are looking even more grim. While Borders and Barnes & Noble still sell music, Borders is not doing well and it looks as though they're going back to their core business of book selling. Amazon is a wonderful account, but one usually shops on Amazon with a particular title in mind. It's so sad. My record collection is largely built on spur-of-the-moment purchases that took place in the aisles of Tower. "Oh, Bobby Timmons? I really like his work with Art Blakey...maybe I should check out this album..." and so on. I'm sure you're more than familiar with the phenom. And suddenly, your house is taken over by records.I know I probably sound like a curmudgeon, but it bothers me that my kids' experience of obtaining music is largely relegated to shopping on iTunes. In truth, they do borrow liberally from my music library, but I remember those days of lying on the living room floor, reading liner notes, memorizing lyrics, and just staring at beautiful album covers. I'm sorry my kids won't replicate that experience, but I guess I shouldn't impose my values on them. It all just makes me a little sad.

At the 1959 Town Hall show the great writer Martin Williams went onstage and talked about Monk's music for 20 or 30 minutes before the music, as if justification was needed to bring Monk's music from the downtown Five Spot to the uptown Town Hall. Then, Monk brought out his quartet and they played four tunes. Then, finally the tentet came out and played the music you can now hear on the Riverside CD.What we did instead, with Tolliver's show, was build a sequence that gave the audience, we hoped, a sense of the architecture of Monk's music. Stanley Cowell came out first and played a magnificent version of In Walked Bud on solo piano. Then he was joined by Rufus Reid on bass and Gene Jackson on drums and they played a swinging Blue Monk. The third tune, Rhythm-a-ning, was played by quartet with Marcus Strickland on tenor. Then Tolliver came out with the rest of the band. During rehearsals it was clear that Tolliver's hand was firmly in control of the first three tunes, even though he wasn't onstage for the performances. There was something distinct he wanted out of each tune to build toward the tentet. Most serious listeners liked both shows. Some preferred one or the other, and a few said they couldn't stand Moran's show, but some advocates of Moran's show were the most passionate of all who have weighed in. I guess that's normal for adventurous new music. We've received a ton of amateur feedback, some of it outlandish. One man in New Canaan, CT emailed the general address for Duke's Center for Documentary Studies, where I work, and complained that in the age of Obama and racial healing there should have been some white people in Moran's band. We were speechless. He also said Moran's music had nothing to do with Monk and everything to do with individual virtuosity. We're speechless at that, too.

The only tune played either night that wasn't played in the original Town Hall concert (both Tolliver and Moran played the same tunes in order) was the gospel tune "Blessed Assurance" (aka "This is My Story, This is My Song") which Moran's tuba player, trumpeter, and trombone player performed as a funeral dirge fadeout as the whole band walked offstage in the middle of the show. A man sitting behind my wife was apoplectic, stammering to everyone within earshot, "This isn't Monk. Monk would never have played a tune like this. This is outrageous." The man obviously hadn't heard Monk's Columbia album Straight No Chaser (the original recording, not the movie soundtrack) in which Monk played exactly that tune in much the same rhythm and phrasing that Moran had the brass trio play it to conclude a sequence that included a Rwandan drum sample in a Nasheet Waits drum solo. The sequence also had film footage shot in fields near the Monk ancestral home - the plantation of Archibald Monk, near Monk's Crossroads - in Newton Grove, N.C. where a number of Monk's relatives still live today. I thought it was extremely unique and powerful. The night before during Tolliver's show there was another man who was hysterical that Tolliver didn't talk to the audience in between tunes, didn't tell the names of the tunes (they were listed in the concert program) nor identify his soloists (all were identified in the program, too). I was told the man was seething with anger even while the band got a tremendous standing ovation after playing Little Rootie Tootie the first time and again after they played it a second time as an encore like Monk did. One of the most heartening aspects of the project was to have around thirty Monk

family members in attendance, and to have trombonist Eddie Bert and French horn player Bob Northern (aka Brother Ah) from Monk's original band. Eddie was backstage before Tolliver's show and I heard Tolliver's trombone player Jason Jackson ask him, "You got any tips for me?" With a look of awe and bewilderment, Eddie said, "No, I don't. All I know is, we rehearsed for a month." Jackson played Eddie's signature parts on "Monk's Mood" beautifully. I met a number of Monk's cousins after the Moran show, including Pam Monk Kelley and Edith Monk Pue. Pam, an educator who has done extensive research on the family tree, asked me if I could attend their family reunion this summer. Her question made me feel better than just about anything that happened all week. It's been a fascinating experience for me and I feel very privileged to have been able to be involved.

Dena De Rose and Marvin Stamm, The Nearness Of Two (Teatro Della Muse). On the heels of De Rose's splendid new trio CD comes the stealth release of the pianist and singer's impromptu partnership with Stamm. She and the trumpeter found themselves in the ancient town of Ancona on Italy's Adriatic coast. A jazz festival producer, Giancarlo Di Napoli (he's Italian), suggested that they do a concert. Stamm and De Rose had never played together until that evening. Indeed, De Rose had never performed in duo with a horn player. They agreed on a repertoire but had no rehearsal. They played in a small hall to open the 2006 Ancona Jazz Festival. Di Napoli recorded the concert. The result is a CD preserving a brilliant instance of what can happen when two improvising musicians meeting for the first time draw on a common language. To digress only slightly, here's a paragraph from Jazz Matters: Reflections on the Music and Some of its Makers:

Dena De Rose and Marvin Stamm, The Nearness Of Two (Teatro Della Muse). On the heels of De Rose's splendid new trio CD comes the stealth release of the pianist and singer's impromptu partnership with Stamm. She and the trumpeter found themselves in the ancient town of Ancona on Italy's Adriatic coast. A jazz festival producer, Giancarlo Di Napoli (he's Italian), suggested that they do a concert. Stamm and De Rose had never played together until that evening. Indeed, De Rose had never performed in duo with a horn player. They agreed on a repertoire but had no rehearsal. They played in a small hall to open the 2006 Ancona Jazz Festival. Di Napoli recorded the concert. The result is a CD preserving a brilliant instance of what can happen when two improvising musicians meeting for the first time draw on a common language. To digress only slightly, here's a paragraph from Jazz Matters: Reflections on the Music and Some of its Makers:

Like every art form, jazz has a fund of devices unique to it and universally employed by those who play it. Among the resources of the jazz tradition available to the player creating an improvised performance are rhythmic patterns, harmonic structures, material quoted from a variety of sources, and "head arrangements" evolved over time without being written. Mutual access to this community body of knowledge makes possible successful and enjoyable collaboration among jazzmen of different generations and stylistic persuasions who have never before played together. It is not unusual at jazz festivals and jam sessions for musicians in their sixties and seventies to be teamed with others in their teens or twenties In the best of such circumstances, the age barrier immediately falls.

Whatever the age difference between Stamm and De Rose, in their collaboration there is not so much as the hint of a barrier. To the contrary, they delight in reaching into that universal fund of devices and employing them to surprise and challenge one another and themselves. It is a journey of discovery that lasts more than an hour, and there is not a lackluster moment.

The musicianship of women who sing, regardless of their instrumental excellence, is often taken for granted. From the beginning here, De Rose's playing on "There Is No Greater Love' obviates any suggestion that she is less than superb as a pianist. Accompanying Stamm, soloing, and engaging in fanciful exchanges with the trumpeter, she is magnificent. She does admit a small defeat during a round of trading four-bar phrases. After Stamm makes his horn growl lustily, she says, "No fair; I can't do that." Otherwise, it's an even match. Seven minutes into the second track, "Corcovado," when she sings her first notes of the concert, it comes as a mild shock to the listener intent on her improvising to realize that this angelic vocalist is the pianist who has been swinging like crazy while rolling out a carpet of rich chords that might make Jobim wish that he had thought of them. I must also observe how effective a dramatic device it is when a good singer makes her appearance only after the band--in this case De Rose and Stamm--has set the stage. That was routine practice in the swing era. It died out after singers emerged from the ranks of sidemen and sidewomen to become featured attractions and more or less take over popular music.

The musicianship of women who sing, regardless of their instrumental excellence, is often taken for granted. From the beginning here, De Rose's playing on "There Is No Greater Love' obviates any suggestion that she is less than superb as a pianist. Accompanying Stamm, soloing, and engaging in fanciful exchanges with the trumpeter, she is magnificent. She does admit a small defeat during a round of trading four-bar phrases. After Stamm makes his horn growl lustily, she says, "No fair; I can't do that." Otherwise, it's an even match. Seven minutes into the second track, "Corcovado," when she sings her first notes of the concert, it comes as a mild shock to the listener intent on her improvising to realize that this angelic vocalist is the pianist who has been swinging like crazy while rolling out a carpet of rich chords that might make Jobim wish that he had thought of them. I must also observe how effective a dramatic device it is when a good singer makes her appearance only after the band--in this case De Rose and Stamm--has set the stage. That was routine practice in the swing era. It died out after singers emerged from the ranks of sidemen and sidewomen to become featured attractions and more or less take over popular music.

Stamm has perfected the art of playing quietly without sacrificing facility, tone, range or expressiveness. Throughout, he executes stirring doubletime passages at the volume of an intimate conversation. His muted solo on "In The Glow of the Moon," a song De Rose wrote with Meredith d'Ambrosio, is just one memorable instance. Another is the counterpoint he initiates in "I'm Old Fashioned." De Rose scats in parallel with her single-note piano lines while the two alternate fours and intertwine melodies with such complexity that any annotator would have to labor long and hard to get them down on paper. A peak of fascination and excitement comes in the blues, Thelonious Monk's "Straight, No Chaser," begun by Stamm, reflective and unaccompanied. It melds into a brisk tempo that launches De Rose into several rollicking choruses, Stamm into several more, and the pair into a succession of their mirror-minded exchanges, then a flying final unison statement of Monk's famous chromatic melody.

expressiveness. Throughout, he executes stirring doubletime passages at the volume of an intimate conversation. His muted solo on "In The Glow of the Moon," a song De Rose wrote with Meredith d'Ambrosio, is just one memorable instance. Another is the counterpoint he initiates in "I'm Old Fashioned." De Rose scats in parallel with her single-note piano lines while the two alternate fours and intertwine melodies with such complexity that any annotator would have to labor long and hard to get them down on paper. A peak of fascination and excitement comes in the blues, Thelonious Monk's "Straight, No Chaser," begun by Stamm, reflective and unaccompanied. It melds into a brisk tempo that launches De Rose into several rollicking choruses, Stamm into several more, and the pair into a succession of their mirror-minded exchanges, then a flying final unison statement of Monk's famous chromatic melody.

There is more; deeply felt performances of "The Nearness of You" and "Imagine;" Stamm soaring on piano updrafts among the heights of the minor intervals in Berlin's "How Deep is the Ocean;" a loving treatment of Clifford Brown's "Joy Spring."

Somewhere back there, I referred to the stealth release of this gem. It is on a small, nearly private, label connected with producer Di Napoli's theater. It is unlikely to show up in your corner record store (as if there were any left), or on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. It is beginning to look as if it is already becoming a collector's item, offered on ebay at an inflated price. This CD deserves a long life and perpetual availability. The realities of the record business being what they are, if I were you I'd grab it while it's still around.

Trying to keep up with new releases, I often get sidetracked by old favorites. It happens that my recent listening coincides with the birthday of two of the listenees.

Lou Levy, Lunarcy (Verve). Levy would have been 81 today. He died in January of 2001. From his post- World War Two beginnings with Georgie Auld through work with Sarah Vaughan, Boyd Raeburn, Woody Herman, Peggy Lee, Ella Fitzgerald, Stan Getz and Frank Sinatra--among many others--Levy was in demand as a band pianist, soloist, and accompanist to major singers. Uncompromising in his musical standards, he was one of the most important pianists initially inspired by Bud Powell, and he made whoever he was playing with sound better. Every so often, I pull out his 1992 CD Lunarcy. Recorded in Los Angeles for the French label Polygram and released in the US by Verve, Lunarcy got less promotion than it deserved. Drummer Ralph Penland and the late Eric Von Essen, a remarkable bassist, complete the rhythm section. Pete Christlieb is on tenor saxophone on most of the tracks. It is a happy collaboration.

World War Two beginnings with Georgie Auld through work with Sarah Vaughan, Boyd Raeburn, Woody Herman, Peggy Lee, Ella Fitzgerald, Stan Getz and Frank Sinatra--among many others--Levy was in demand as a band pianist, soloist, and accompanist to major singers. Uncompromising in his musical standards, he was one of the most important pianists initially inspired by Bud Powell, and he made whoever he was playing with sound better. Every so often, I pull out his 1992 CD Lunarcy. Recorded in Los Angeles for the French label Polygram and released in the US by Verve, Lunarcy got less promotion than it deserved. Drummer Ralph Penland and the late Eric Von Essen, a remarkable bassist, complete the rhythm section. Pete Christlieb is on tenor saxophone on most of the tracks. It is a happy collaboration.

Carol Sloane, Dearest Duke (Arbors). This is also Sloane's birthday. As far as I know, Dearest Duke is her most recent CD. Full disclosure that I am not an impartial observer of this music: I wrote the liner notes. This excerpt will give you an idea of my enthusiasm for her work in this collection of Ellington songs.

Carol Sloane, Dearest Duke (Arbors). This is also Sloane's birthday. As far as I know, Dearest Duke is her most recent CD. Full disclosure that I am not an impartial observer of this music: I wrote the liner notes. This excerpt will give you an idea of my enthusiasm for her work in this collection of Ellington songs.

What is a jazz singer? There is no reliable definition, but there is an answer. Carol Sloane is a jazz singer. If she scats one note in a thousand, I'd be surprised. I would not be surprised if that note was full of the spirit of jazz. Vocalists have scatted entire songs, entire sets, without a glimmer of the jazz feeling that Sloane achieves with three words of a ballad.

This is not idle liner note chatter. We have evidence at hand. One minute and six seconds into "Sophisticated Lady," hear how she employs phrasing, intonation and melodic ingenuity as she sings "...soon grow wise." It is a gem of a moment in a compelling performance. Sloane finds the heart of Duke Ellington's tune and makes the most of Mitchell Parish's lyrics. In her care, the awkward line, "...and when nobody is nigh," seems absolutely right.

Next time, more recent listening and, possibly, more detachment.

If you have wondered how those concerts turned out that celebrated the 50th anniversary of Thelonious Monk's Town Hall concert, Will Friedwald reported on them for The Wall Street Journal. As we mentioned last week in this Rifftides post, the bands were led by Charles Tolliver and Jason Moran. Here's an excerpt from Friedwald's review of the events.

If you have wondered how those concerts turned out that celebrated the 50th anniversary of Thelonious Monk's Town Hall concert, Will Friedwald reported on them for The Wall Street Journal. As we mentioned last week in this Rifftides post, the bands were led by Charles Tolliver and Jason Moran. Here's an excerpt from Friedwald's review of the events.

The first night, Mr. Tolliver and his musicians reveled in the duality of Monk's music -- his basic themes are so simple that an amateur can easily pound one out on the piano, but to capture the nuances and the subtleties of his compositions takes a lifetime of study, even for the current generation of players who grew up on Monk's tunes and studied them formally in music school.

On Thursday night, Mr. Tolliver and his men got those nuances almost exactly right. Starting, as the original concert did, with solo, trio and quartet pieces, pianist Stanley Cowell captured Monk's spirit without mimicking every little dynamic of every little note.

To read the whole thing, go here.

Don't play what's there. Play what's not there.--Miles Davis

Simplicity is the highest goal, achievable when you have overcome all difficulties. After one has played a vast quantity of notes and more notes, it is simplicity that emerges as the crowning reward of art.--Frederic Chopin

Rests always sound well.--Arnold Schoenberg

Fifty years ago today, the Miles Davis Sextet began recording for Columbia Records the music that ultimately made up the album called Kind Of Blue. To observe the occasion, Jan Stevens of The Bill Evans Web Pages commissioned an essay about that imperishable recording and its most recent CD reissue. The piece, by John Varrallo, is exclusive to the Evans site. It is worth reading.

Fifty years ago today, the Miles Davis Sextet began recording for Columbia Records the music that ultimately made up the album called Kind Of Blue. To observe the occasion, Jan Stevens of The Bill Evans Web Pages commissioned an essay about that imperishable recording and its most recent CD reissue. The piece, by John Varrallo, is exclusive to the Evans site. It is worth reading.

Evans, who was central to the concept of the music on Kind Of Blue, had left the band by the time Davis appeared on CBS-TV's Robert Herridge Theater in April of 1959. Wynton Kelly was now the pianist. John Coltrane was still on tenor saxophone, with Jimmy Cobb and Paul Chambers on drums and bass. Later in April, Evans returned to the band, but only to complete the final tracks for the album. Alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley is not on the television program. In this performance, the quintet is enhanced by three trombones, one of them played by Frank Rehak. You will see Gil Evans and the large orchestra that played with Davis in other segments of the broadcast. Herridge introduces the album's most famous piece.

Columbia/Sony/Legacy has added to the chain of Kind Of Blue CD reissues an elaborate package that includes two CDs, a DVD and a vinyl long-playing record of the original album.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary