Rifftides: January 2009 Archives

CD: Tom Harrell, Prana Dance (High Note)

The economy, lyricism and ingenuity in Tom Harrell's writing and his trumpet and flugelhorn playing make him one of the most admired musicians in jazz. Not only his contemporaries, but also musicians of younger and older generations are in awe of Harrell's musicianship. When he was a member of Phil Woods' quintet In the 1980s, Woods made the frequently-quoted statement that he had never played with a better musician. With two decades of leadership and growth since then, Harrell has gone on to occupy a position of esteem comparable to that of Woods himself and of Wayne Shorter, two of the few living jazz artists with similar all-'round capability and depth of creativity.

Harrell writes and he plays. As you know if you've seen him at work, there is no show business component to his performance except in the irony that his catatonic state onstage when he's not playing constitutes a kind of riveting non-showmanship. In a marvel of courage, dedication and modern medicine, a man who suffers from paranoid schizophrenia overcomes his condition to create music at the level of genius.

Harrell's Prana Dance, recorded last May, is with the same quartet that made Light On two years earlier. Again, the compositions are all Harrell's. This is one instance in which you won't find me complaining that there are no standard songs. Like Shorter, Herbie Hancock and Horace Silver, Harrell delivers an album full of original works that have substance and will endure. To single out three, "Prana," "Maharaja" and "Ride" have the structural simplicity and harmonic magnetism to stay in the mind after only a hearing or two. Those are characteristics of many of Harrell's compositions.

What he and the increasingly impressive tenor saxophonist Wayne Escoffery do with these attractive and deceptively simple songs is crucially important to the success of the album. As Neil Tesser points out in his evocative liner notes, you can hear, or feel, Harrell and Escoffery thinking their way through solos. And yet, spontaneity and a sense of discovery dominate the improvisation. The young rhythm section of pianist Danny Grissett, bassist Ugonna Okegwo and drummer Johnathan Blake is splendid. Often when a pianist switches from the Steinway to play electric piano, I clench my teeth. Although I'd rather hear him play the acoustic instrument, Grissett adapts the Fender Rhodes to some of these tunes in a way that makes it the right choice for the material.

Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Art Farmer, Clifford Brown, Blue Mitchell and Chet Baker figured in Harrell's education as he developed his conception. If out of fond tribute he occasionally alludes to them in his solos, it is with subtlety, originality and - often - humor. Harrell has long since evolved into an original. In tone, style, choice of notes and the ability to reach his listeners' emotions, he is a worthy successor to his heroes. Prana Dance is an immensely satisfying album.

The video below is of Harrell's quintet at a club in Paris with Xavier Davis on piano and Jimmy Greene on tenor saxophone. Okegwo is the bassist. The drummer is unidentified.

As New Orleans makes its slow way back from the devastation of hurricane Katrina and the fumbling federal and state crisis response, there are rays of hope on the cultural front. The jazz journalist Larry Blumenfeld, who has become a semi-permanent New Orleans resident, writes about it in The Wall Street Journal.

Landrieu (then U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development), Morial and Armstrong's wife Lucille dedicated Armstrong Park on April 15, 1980, nine years after Armstrong's death. It has a long way to go to become the Tivoli Gardens of America, but the developments Blumenfeld describes give hope that it will blossom despite the city's setbacks.

Landrieu (then U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development), Morial and Armstrong's wife Lucille dedicated Armstrong Park on April 15, 1980, nine years after Armstrong's death. It has a long way to go to become the Tivoli Gardens of America, but the developments Blumenfeld describes give hope that it will blossom despite the city's setbacks.

Once alight with bulbs that spelled out "Armstrong," the large steel archway above North Rampart Street, across from the venerable Donna's Bar & Grill, was dark much of the past decade, largely rusted. Beneath it, the main gate to a park named for trumpeter Louis Armstrong had been padlocked for more than three years, save for the occasional special event. Just inside, Congo Square -- where two centuries ago enslaved Africans and free people of color spent Sundays dancing and drumming to the bamboula rhythm, seeding the pulse of New Orleans jazz -- had been effectively off limits. The adjacent Mahalia Jackson Theater of the Performing Arts, home to opera and ballet performances for more than 30 years, sat empty and in need of repair after taking on 14 feet of water in 2005.

It would be hard to find a more potent symbol of the tenuous state of musical life and cultural history in a city largely defined by both. But earlier this month, shortly after dusk, Mayor C. Ray Nagin flipped a switch -- just a prop, it turned out, for dramatic effect -- and on went the lights of the arch and the park's streetlamps. As the Original Pin Stripe Band played "Bourbon Street Parade," a small mock second-line parade wound its way around a bronze statue of Armstrong and over to a sparkling Mahalia Jackson Theater for a free concert, the first in a series of events spanning 10 days and a broad range of performing arts.

To read all of Blumenfeld's article, go here.

What his readers may not know is how trumpeter Clark Terry inspired the movement that got New Orleans its Armstrong statue. It happened forty years ago next summer. I told the story in the Terry chapter of Jazz Matters: Reflections on the Music and Some of its Makers, originally a 1978 article in Texas Monthly.

Terry's ties to the city have been more spiritual than personal, but his admiration for a New Orleans hero led almost a decade ago to one of the most important gestures of his life. A few blocks from the Super Dome a monument to Louis Armstrong is nearing completion. It might very well not have been built without Terry's inspiration.

New Orleans's Armstrong Park has been a project of the administration of former mayor Moon Landrieu, who deserves full credit for paying tangible tribute to the city's greatest artist. But impetus for the idea came in 1969 on a bus ride during the second New Orleans Jazzfest. As a musicians' tour was passing Jane Alley, Armstrong's birthplace, Terry deplored that fact that while New Olreans seemed to have statues of half the Latin American presidents in history, there were none of the city's most famous son. Then and there, he started a fund to commission a statue. His first dollar was symbolic. His organizing ability and leadership were much more. Nine years later, that statue is on the verge of becoming the centerpiece of an entire park dedicated to Armstrong's memory. The park's completion slowed in the six-month transition period between Landrieu's administration and that of Mayor Ernest Morial. But assuming that Morial, the city's first black mayor, gets behind the project, Armstrong Park should be the New Orleans equivalent of Copenhagen's celebrated Tivoli Gardens and open by 1980.

Landrieu (then U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development), Morial and Armstrong's wife Lucille dedicated Armstrong Park on April 15, 1980, nine years after Armstrong's death. It has a long way to go to become the Tivoli Gardens of America, but the developments Blumenfeld describes give hope that it will blossom despite the city's setbacks.

Landrieu (then U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development), Morial and Armstrong's wife Lucille dedicated Armstrong Park on April 15, 1980, nine years after Armstrong's death. It has a long way to go to become the Tivoli Gardens of America, but the developments Blumenfeld describes give hope that it will blossom despite the city's setbacks.  Dave Frishberg lives very much in the present but makes no bones about his fascination with the past. After all, his last CD was titled Retromania. So it's no wonder that the producers of a new piece of musical theater sought out Frishberg to write the words and music. Anyone familiar with "I'm Hip," "My Attorney Bernie," "Peel Me a Grape," "Listen Here" or his dozens of other songs knows that he's prepared to capture irony, whimsy and tenderness.

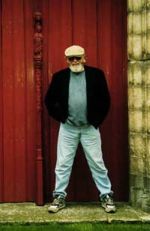

Dave Frishberg lives very much in the present but makes no bones about his fascination with the past. After all, his last CD was titled Retromania. So it's no wonder that the producers of a new piece of musical theater sought out Frishberg to write the words and music. Anyone familiar with "I'm Hip," "My Attorney Bernie," "Peel Me a Grape," "Listen Here" or his dozens of other songs knows that he's prepared to capture irony, whimsy and tenderness.

The show, Vitriol & Violets, is about the Algonquin Round Table, the group of writers and their cronies who gathered nearly every day at New York's Algonquin Hotel through the 1920s to exercise their wit. One of them later called it "the ten-year lunch." Among the verbal fencers were Dorothy Parker, Alexander Woollcott, Robert Benchley, Harold Ross, George S. Kaufman, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun and Harpo Marx. You may recognize the celebrated Al Hirschfeld drawing of a typical meeting.

The dialogue in the show is fashioned by writers Shelly Lipkin, Louanne Moldovan, and Sherry Lamoreaux from published works or frequently quoted sayings of the Round Table members. The show opened off Broadway - 3000 miles off Broadway - last weekend in Portland, Oregon, Frishberg's base of operations for many years. It continues next weekend, Friday through Sunday. The top ticket price, 25 dollars, is definitely off-Broadway. Here's a brief review by Marty Hughley in OregonLive.com,the Portland Oregonian's online edition.

...a dimly lit room in the Scottish Rite Center provided a fitting atmosphere for "Vitriol & Violets," which tracks the careers and friendships of the 1920s Algonquin Round Table. The story presents a lot of characters to follow, but the witticisms flow freely, the songs by Dave Frishberg are alternately hilarious and deeply poignant, and a cast featuring Adair Chappell (charmingly acerbic as Dorothy Parker), Joe Theissen, Isaac Lamb and others pulls it off with appropriate panache.

For more information, go here.

Those of us who can't make it to Portland for the show can hope for a New York run, a road version or - at the very least - an original cast recording.

Not long after I posted the item above, Mr. Frishberg sent this:

The show is running smoothly, and the audience seems to love it. It's a small space, 99 seats, no proscenium, so it's like 3/4 in-the-round. Actors play practically in the laps of the audience. There are six musical events in the show, and all are warmly received. The cast is wonderful; the best singers are Dorothy Parker and Heywood Broun. Just piano accompaniment (not by me). Four performances left, including two matinees. The play seems a natural for off Broadway in New York. I hope it happens. It's been a challenging and rewarding project, and I'm glad it's over.

The current offering on Steve Cerra's Jazz Profiles web log is part one of an extensive  examination of the career and music of alto saxophonist Bud Shank. It incorporates most of the contents of the booklet I wrote for the Mosaic Records boxed set The Pacific Jazz Bud Shank Studio Sessions (1956-1961), long out of print. As he always does, Steve includes personal recollections and lots of photographs. Here is a short excerpt from the Mosaic notes, Shank talking about west coast jazz.

examination of the career and music of alto saxophonist Bud Shank. It incorporates most of the contents of the booklet I wrote for the Mosaic Records boxed set The Pacific Jazz Bud Shank Studio Sessions (1956-1961), long out of print. As he always does, Steve includes personal recollections and lots of photographs. Here is a short excerpt from the Mosaic notes, Shank talking about west coast jazz.

examination of the career and music of alto saxophonist Bud Shank. It incorporates most of the contents of the booklet I wrote for the Mosaic Records boxed set The Pacific Jazz Bud Shank Studio Sessions (1956-1961), long out of print. As he always does, Steve includes personal recollections and lots of photographs. Here is a short excerpt from the Mosaic notes, Shank talking about west coast jazz.

examination of the career and music of alto saxophonist Bud Shank. It incorporates most of the contents of the booklet I wrote for the Mosaic Records boxed set The Pacific Jazz Bud Shank Studio Sessions (1956-1961), long out of print. As he always does, Steve includes personal recollections and lots of photographs. Here is a short excerpt from the Mosaic notes, Shank talking about west coast jazz."I don't even know what the hell west coast jazz is," he said, with

exasperation and no wry laugh. "It was something different from what they were doing in New York, so the critics called it west coast jazz. That Miles Davis BIRTH OF THE COOL album, out of New York, probably started west coast jazz. It was also very organized, predetermined, written. It was a little bit more intellectual, shall I say, than had happened before. Jimmy Giuffre, Buddy Childers, Shorty, Shelly Manne, Marty Paich, Bob

Cooper, almost everybody involved; we all came from somewhere else, New York, Texas, Chicago, Ohio. The fact that we were in L.A. around the orange trees had nothing to do with it. I really think that everybody played the way they would have played no matter where they were. New York writers, they're the ones who invented west coast jazz."

"Those bastards," I said.

"Those bastards," he said, laughing uproariously.

To read the whole thing, go here.

Benny Golson celebrates his 80th birthday today. At the same time, he releases a new CD with a band in the mold of the Jazztet that he and Art Farmer led beginning in 1960. The Jazztet's success put Golson's composing and arranging abilities into the consciousness of listeners who may have been unaware of his history. He played a key role in the revitalization of Art Blakey's career. At 28, when he was seasoned but mainly known only in the jazz inner circle, Golson took over as music director of the drummer's Jazz Messengers in 1958. The band had been generating excitement, but Golson persuaded Blakey that its lacked substance. Golson told me the story when I was writing notes for Art Blakey And The Jazz Messengers, Paris1958. Their relationship began with a telephone call.

Benny Golson celebrates his 80th birthday today. At the same time, he releases a new CD with a band in the mold of the Jazztet that he and Art Farmer led beginning in 1960. The Jazztet's success put Golson's composing and arranging abilities into the consciousness of listeners who may have been unaware of his history. He played a key role in the revitalization of Art Blakey's career. At 28, when he was seasoned but mainly known only in the jazz inner circle, Golson took over as music director of the drummer's Jazz Messengers in 1958. The band had been generating excitement, but Golson persuaded Blakey that its lacked substance. Golson told me the story when I was writing notes for Art Blakey And The Jazz Messengers, Paris1958. Their relationship began with a telephone call.

"It was my hero," Golson says. "Art Blakey was on the phone. One of his guys was having trouble getting a cabaret card from the police and he asked me to come In and sub for a night. 'Oh, my God,' I said to myself, 'Art Blakey.' He didn't know it, but I would have played for free. And I went down and played, and I noticed that although the band had been together for a while, not much was happening; just tunes. But, on a personal level, he just laid me out. I'd never played with a drummer like that before."

Blakey asked him back a second night and then for the weekend. By now, Golson though to inquire about money, and when he found out how little the band was making,

he took his leader aside for a little chat. "I said, 'Art, you're a great man. This pay is nothing for you. It makes me sad.' And he looked at me with his sad, beautiful cow eyes and said 'Can you help me?' And I can't believe what came out of my mouth, this young upstart who hadn't been in New York too long. "I said, 'Yes, if you'll do exactly what I tell you.'

"How dared I?" Golson asks, laughing. "But he went for it. He said, 'What should I do?' And I said, 'Get a new band.'"

He agreed, gave the men notice and on Golson's recommendation hired a new set of Jazz Messengers, all from Benny's home town. On trumpet was Lee Morgan, barely 20 years old, a fellow alumnus of the Gillespie big band. Morgan had sat in with the drummer in Philadelphia as a prodigy of 15, and the previous year had recorded two pieces with an expanded version of the Messengers. The pianist was 26-year-old Bobby Timmons, and on bass was Jymie Merritt, at 31 three years older than Golson and like him a veteran of the Bull Moose Jackson rhythm and bues band of the early 1950s.

"What's all this Philadelphia stuff?' Blakey said. I told him 'Trust me.'"

Golson took over the reconstituted band and ran it for Blakey, handling everything from uniforms and payroll to new arrangements.

The edition of the Messengers that Golson remade was a landmark group in the evolution of what came to be known as hard bop, in great part because of Golson's stewardship and the compositions and arrangements he contributed. It was also the point of departure for change in Golson's playing. He told me that before his Blakey experience, his improvisation was "smooth and syrupy." Others have called it stiff. Blakey did not abide stiffness in his band. He used his press roll on sluggish soloists the way a Marine Corps drill instructor I knew intimately used his rifle butt on the rear ends of recalcitrant officer trainees. By the time he moved on after more than a year with Blakey, Golson was a considerably tougher tenor player.

Since then, his organizational abilities and multifaceted musicianship have seen him through a six-decade career including the leadership of bands, composing and arranging for movies and television and cultural diplomacy for the U.S. on State Department tours. Many of his tunes are staples of the jazz repertoire, among them "Blues March," "Stablemates," "Killer Joe," "I Remember Clifford" and "Whisper Not."

In his Concord CD, New Time, New 'Tet, the instrumentation is the same as The Jazztet's - tenor sax (Golson), trumpet (Eddie Henderson), trombone (Steve Davis), piano (Mike LeDonne), bass (Buster Williams) and drums (Carl Allen). Three of the tracks feature Golson compositions. "Whisper Not" is there, with Al Jarreau as a guest, singing the words that Leonard Feather put to the tune years ago. All of the music is enriched by Golson's harmonic resourcefulness. He includes ingenious treatments of pieces by Chopin and Verdi, Thelonious Monk's "Epistrophy" and Sonny Rollins's "Aerigin." He reaches deep into his store of harmonic ingenuity to fashion the rhythm and blues performer El DeBarge's "Love Me in a Special Way" as a solo vehicle for Davis, LeDonne and Henderon and for one of Golson's most touching ballad solos on record. Golson's "Gypsy Jingle-Jangle," with an Ellington-Strayhorn caste to more than its title, is a romp, particularly for Henderson, who manages astonishing interval leaps in his solo. Golson"s "From Dream to Dream" and "Uptown Afterburn," firmly established in his canon, get new interpretations here.

As Scott Simon's guest on National Public Radio's Weekend Edition Saturday, Golson was articulate, self-effacing and humorous in talking about his music and career. To hear the interview on the NPR web site, click here, then scroll down to "Listen Now."

Minus Henderson and with Curtis Fuller on trombone, here is video of the Golson group with one of his most famous compositions, "Along Came Betty," in two clips

Benny Golson: 80 years old and going strong.

By tradition and general agreement in the reviewing trade, it is considered unprofessional and tacky to write about a recording to which one has contributed liner notes. Therefore, I have not written about Rebecca Kilgore's and Dave Frishberg's Why Fight The Feeling?, a collection of songs by Frank Loesser. However, I have no qualms about alerting you to the welcome fact that Carol Sloane has switched on her blog after a month of reticence. She posts a number of items, in one of which she writes:

By tradition and general agreement in the reviewing trade, it is considered unprofessional and tacky to write about a recording to which one has contributed liner notes. Therefore, I have not written about Rebecca Kilgore's and Dave Frishberg's Why Fight The Feeling?, a collection of songs by Frank Loesser. However, I have no qualms about alerting you to the welcome fact that Carol Sloane has switched on her blog after a month of reticence. She posts a number of items, in one of which she writes: Rebecca sings the songs to perfection. No fuss, no unnecessary embellishment, dead-on pitch. Hers is a cheery sounding voice and her diction is impeccable. My kind of singer. Dave's jaunty piano style is the perfect compliment for her, and they include a great many verses sinfully ignored by many.

Amen. To find Sloane and read her recent post, click here.

Here is Ms. Kilgore enjoying herself and the company she's in at a jazz festival in downtown Europe. The song is not by Loesser, but by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh. Her co-conspirators are:

Michael Supnick (trombone), Evan Christopher (clarinet), Rossano Sportiello (piano), Lino Patruno (guitar), Guido Giacomini (bass), Giampaolo Biagi (drums). Ascona(Switzerland), July 5, 2001

Gentle, soulful David Newman is gone. He died on Monday.

"Fathead" was a nickname that became a promotional tag, but those close to him knew him as David. They seemed always to say the name with affection whether they were speaking to or about him. He once told the story of his nickname.

I was in band class and I had this music on my music stand but it was upside down ... He [Mr. Miller] knew I could barely read the music right side up. He thumped me on the head and called me 'Fathead.' My classmates laughed. After that, it became my trademark. I don't consider it derogatory and it doesn't offend me. If someone asked me what I prefer to be called, it would be David. But Fathead doesn't bother me at all.

Newman was one of Ray Charles's favorite musicians from the time Charles emerged as a star. He recorded his biggest success, "Hard Times," at a 1958 session for which Charles was producer, arranger and pianist. The piece became his signature tune.

For the last year of his life, he kept on playing as long as he could despite the pancreatic cancer that finally slowed him. Often, he appeared with student musicians, whom he loved to teach and encourage. From my notes for one of his last CDs:

As he approaches his mid seventies, David Newman's pace is not slower; he is merely moving toward different audiences. Like many jazz musicians, he tries to stay away from clubs, with their late hours and the smoke his doctor says he must avoid. The success of his CDs and of a film about Ray Charles put him in greater demand than ever. He is accepting concert offers, playing festivals and doing clinics.

At one of his concerts recently, his encore was a B-flat blues with a searing flute solo. He and the sixteen-piece band from Central Washington University rocked the hall and got a standing ovation. Newman smiled when I remarked on it later, then delivered what for him was an effusion of self-satisfaction. "Yes, I was very pleased with that," he said

Here is David Newman in a recent performance of the song from which he was inseparable. The video is shaky and cuts off the second his solo ends, but it is a fine solo and a fine way to remember him.

Rifftides Washington, DC, correspondent John Birchard recently renewed his enthusiasm for a great singer.He checks in with a review.

CARMEN MCRAE: AN APPRECIATIONBy John Birchard

According to Netflix, the DVD Carmen McRae: Live is valued at three stars. Don't believe it. I watched it last night and was transported by the woman's artistry. The Tokyo concert was recorded in 1986 and released by Image Entertainment.

Accompanied by a superb rhythm section

(Pat Coil, piano; Bob Bowman, bass; Frank Felice, drums), Carmen cruises through some of the best of The Great American Songbook, opening with "That Old Black Magic" and "I Get Along Without You Very Well." By the time she gets to "I Concentrate on You", her pipes are thoroughly warmed and she's taking chances with the melody, going down the scale when you expect her to go up, growling, sliding into a note the choice of which leaves one laughing with delight.

Now, about scatting: I'm not a big fan of the technique, but Carmen McRae reminded me that certain people can handle it. First, she didn't overdo it, running out of ideas before exhausting her enthusiasm. Her scatting was musicianly, sometime funny and always inventive. Aspiring jazz singers would benefit from watching this disc.

Her technique with the hand microphone was a lesson in the art of dynamics. Depending on the effect she was going for, the mic would be close to her lips at one moment, then pulled away to accomplish a fade effect. That's what experience does for an artist.

Carmen's concert was an exercise in what Whitney Balliett had in mind when he called jazz, "the sound of surprise." On a turbocharged "Thou Swell", when one would expect a racehorse gallop into scat-land and a long, noisy drum solo, the whole thing was over in not much more than a minute - fast, tightly arranged, no scat, no drum solo. Just a breath-taking display of musicianship.

During this one-hour-21-minute concert, she reminded me how few singers really pay attention to lyrics. Carmen told stories, emphasized words in a way that, no matter how familiar the song, brought fresh attention to the story it told. With her, words meant something. By altering her volume from a belt to a whisper and tinkering with the melody, a song she might have sung a thousand times became new again. Besides the familiar standards, she salted the program with lesser-known tunes such as "Getting Some Fun Out of Life", "Love Came On Stealthy Fingers" and "As Long As I Live", the latter featuring her own accompaniment on acoustic piano. She took it at a walking tempo and the way she used the left hand in her solo reminded me of Jimmy Rowles.

There is so much to like on this DVD, from her sly use of musical humor to a hardly noticeable tapping of her finger on the edge of the piano to signal Pat Coil the tempo she wanted to slip into after beginning the Brazilian song "Dindi" a cappella. The word diva is tossed around with reckless abandon these days, applied to practically any teen-age phenom who has two hits in a row. Carmen McRae was a diva - not that easy to work for, demanding high standards from her musicians and herself. When she took the stage, SHE TOOK THE STAGE. There was no question this lady was in charge and she delivered with professionalism and artistry.

Carmen McRae's death left a huge hole that remains to be filled. If Netflix believes this DVD is worth only three stars, I would like to experience a singer whose work is rated at five.

Those interested in owning, rather than renting, the McRae DVD will find it by clicking here.

The publisher of Poodie James has good news for you, if not for my royalty statements. He has reduced the price. If you have yet to pick up a copy, be advised that the book is available here and here. From a review:

The publisher of Poodie James has good news for you, if not for my royalty statements. He has reduced the price. If you have yet to pick up a copy, be advised that the book is available here and here. From a review: I'll cut to the chase: Poodie James is a very good book. Not only is it handsomely and lyrically written, but Ramsey's snapshots of small-town life circa 1948 are altogether convincing, and he has even brought off the immensely difficult trick of worming his way into the consciousness of a deaf person without betraying the slightest sense of strain... Ramsey is no less adept at sketching the constant tension between tolerance and suspicion that is part and parcel of the communal life of every small town.

-- Terry Teachout, commentarymagazine.com

To read the full review, go here.

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the

bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether. - Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865

We will not apologize for our way of life, nor will we waver in its defense, and for those who seek to advance their aims by inducing terror and slaughtering innocents, we say to you now that our spirit is stronger and cannot be broken; you cannot outlast us, and we will defeat you. - Barak Obama, Inaugural Address, January 20, 2009

The Gabriel Alegria Sextet enlivened and intrigued the audience at The Seasons Saturday night. The group of five young Peruvians and a South African meld strains from American,  Peruvian and African music into a sophisticated hybrid with which they are writing a new chapter in the history of Latin jazz. Since earning an advanced degree in music from the University of Southern California, Alegria has spent several years refining his concept of Afro-Peruvian music. His fluency as a trumpet player is matched by his skills as a composer, arranger and leader. He has assembled a band of kindred spirits whose joy in performing seduces his listeners to receive with enthusiasm music that is often as challenging as any in the most adventurous modern jazz.

Peruvian and African music into a sophisticated hybrid with which they are writing a new chapter in the history of Latin jazz. Since earning an advanced degree in music from the University of Southern California, Alegria has spent several years refining his concept of Afro-Peruvian music. His fluency as a trumpet player is matched by his skills as a composer, arranger and leader. He has assembled a band of kindred spirits whose joy in performing seduces his listeners to receive with enthusiasm music that is often as challenging as any in the most adventurous modern jazz.

Peruvian and African music into a sophisticated hybrid with which they are writing a new chapter in the history of Latin jazz. Since earning an advanced degree in music from the University of Southern California, Alegria has spent several years refining his concept of Afro-Peruvian music. His fluency as a trumpet player is matched by his skills as a composer, arranger and leader. He has assembled a band of kindred spirits whose joy in performing seduces his listeners to receive with enthusiasm music that is often as challenging as any in the most adventurous modern jazz.

Peruvian and African music into a sophisticated hybrid with which they are writing a new chapter in the history of Latin jazz. Since earning an advanced degree in music from the University of Southern California, Alegria has spent several years refining his concept of Afro-Peruvian music. His fluency as a trumpet player is matched by his skills as a composer, arranger and leader. He has assembled a band of kindred spirits whose joy in performing seduces his listeners to receive with enthusiasm music that is often as challenging as any in the most adventurous modern jazz.

The concert included most of the pieces on Alegria's CD, the appropriately titled Nuevo Mundo (New World). In nearly every one, multifaceted rhythms buoyed beguiling melodies, as in the

aching beauty of "El Mar" and the simulated horses' clip-clops of Freddy "Huevito" Lobatón's percussion in "El Norte." In some pieces, the melodic and harmonic components suggest Herbie Hancock of the Maiden Voyage period or certain aspects of Wayne Shorter's writing. That is due in part to the

harmonic and tonal blend of Alegria's trumpet or flugelhorn with Laurandrea Leguia's tenor saxophone, but Hancock and Shorter never had rhythms like these. Lobatón's and drummer Hugo Alcazar's percussive inventions run under, around and through the proceedings so that shifting rhythms are at the heart of virtually everything the band plays.

In "El Norte," Lobatón, guitarist Yuri Juarez and bassist Ramon de Bruyn became a band within a band, tending a patch of rhythmic growth all their own. de Bruyn frequently adds wordless singing as a third voice in the horn ensemble. There is a lot going on in this band. Toward the end of the evening, Lobatón came off the stage, stepped onto a large sheet of wood down front and demonstrated the Peruvian zapateo dancing of which he is said to be one of the country's leading masters. He had as much percussion dexterity and inventiveness with his feet on the floor as with his hands on the cajon, cajita and quijada. In a post-intermission conversation on stage, Alegria said that, for all of their serious musical intentions, the band's primary goal is to spread joy and make people happy. Saturday night, they succeeded.

The Nuevo Mundo CD has impressive guest appearances by trumpeter Bobby Shew, trombonist Bill Watrous, pianist Russell Ferrante and singers Tierney Sutton and Lisa Harriton. On its own, the Alegria band is touring the US through early March. For the schedule, click here.

Rifftides reader Gary Alexander has some thoughts about what he sees as a watershed year for jazz back when popular culture had not yet been reshaped by rock and roll. Mr. Alexander broadcasts a jazz program Mondays and Fridays 3:00 to 5:30 p.m. PST, from KLOI on Lopez Island, Washington. If you are among the 2,200 (+ -) people who live on that  enchanting island in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, you may know that KLOI is at 102.9 FM. If you are one of the 6-billion-800-million others (+ -), your best bet is to listen to Mr. Alexander on the web. Go here and scroll down to where it says, "Click Here To Listen To The Stream." The opinions Mr. Alexander offers in the following piece are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Rifftides staff. On the other hand--to take a firm stand on the matter--maybe they do.

enchanting island in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, you may know that KLOI is at 102.9 FM. If you are one of the 6-billion-800-million others (+ -), your best bet is to listen to Mr. Alexander on the web. Go here and scroll down to where it says, "Click Here To Listen To The Stream." The opinions Mr. Alexander offers in the following piece are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Rifftides staff. On the other hand--to take a firm stand on the matter--maybe they do.

enchanting island in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, you may know that KLOI is at 102.9 FM. If you are one of the 6-billion-800-million others (+ -), your best bet is to listen to Mr. Alexander on the web. Go here and scroll down to where it says, "Click Here To Listen To The Stream." The opinions Mr. Alexander offers in the following piece are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Rifftides staff. On the other hand--to take a firm stand on the matter--maybe they do.

enchanting island in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, you may know that KLOI is at 102.9 FM. If you are one of the 6-billion-800-million others (+ -), your best bet is to listen to Mr. Alexander on the web. Go here and scroll down to where it says, "Click Here To Listen To The Stream." The opinions Mr. Alexander offers in the following piece are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Rifftides staff. On the other hand--to take a firm stand on the matter--maybe they do.1959: The Year Jazz Was RebornBy Gary L. Alexander

Early in the morning of February 3, 1959, the chartered Beechcraft Bonanza carrying Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and J.R. "Big Bopper" Richardson crashed just after take-off near Clear Lake, Iowa. It was shocking news, similar to what jazz fans felt when Charlie Parker died ("Bird Lives") four years before, in March 1955. Later singers like Don McLean called this crash "the day the music died."

I beg to differ. Later that same day, the Miles Davis sextet (absent Miles) recorded

The Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago, the first of three phenomenal new albums - all included John Coltrane - in the first half of 1959 alone. As the 50th anniversary of the Buddy Holly crash arrives this year, rock musicians and cultural pundits will mourn the death of these three vital voices at their peak of popularity in their golden age of rock'n'roll, but jazz musicians can celebrate the rebirth of their own music.

In the six months of 1959 - particularly the four months between the famous crash on February 3 and the end of May - jazz was almost literally reborn, with ground-breaking albums like Miles Davis and his all-star sextet in the celebrated perennial best-seller, Kind Of Blue which was mostly recorded on March 2 of 1959. That album, a best-seller

each year since, introduced modal music to many listeners, while albums recorded in the same season contained the most forward-looking avant-garde music. Giant Steps, John Coltrane's post-"sheets of sound" excursion, was mostly recorded on May 5, the same day that Ella Fitzgerald captured many of the first Grammy awards in ceremonies dominated by jazz and swing-related music.

Ella was busy recording her largest "Songbook" offering, the 53-song George And Ira Gershwin Songbook recorded from January to July of 1959. In the

same period, Thelonious Monk recorded his famous Town Hall Concert (on February 28) and Charles Mingus perhaps his best album, Mingus Ah-Um (in May). Looking forward, Ornette Coleman offered us The Shape of Jazz to Come. At mid-year, Dave Brubeck recorded odd-time compositions in Time Out on June 25 and July 1.

The rest of America was fairly hip in those months. The #1 jazz hit in 1959 was the "Theme from Peter Gunn," written by Henry Mancini and played by Ray Anthony's big band. It was in the Billboard Top 40 from January 19 to April 13, 1959, peaking at #8. The #1 hit for 1959 was a song written by Kurt Weill for a German opera in the 1920s, "Mack the Knife" (recorded in late 1958 and reaching #1 for 9 of 10 weeks in late 1959, a huge hit for Bobby Darin). As you can see, the #1 hits for the first half of 1959 were better-than-average pop songs.

#1 Billboard Hits its in Early 1959

"Smoke Gets in Your Eyes," by the Platters (#1 for 3 weeks, January 19 to February 8) "Stagger Lee," by Lloyd Price (4 weeks): February 9 to March 8

"Venus," by Frankie Avalon (5 weeks): March 9 to April 12

"Come Softly to Me," by the Fleetwoods (4 weeks): April 13 to May 10

"Kansas City," by Wilbert Harrison (3 weeks): May 11 to May 31

"The Battle of New Orleans," by Johnny Horton (6 weeks): June 1 to July 12

Jazz singers fared reasonably well on the Hit Parade, too. "Broken-Hearted Melody," by Sarah Vaughn, charted for 11 weeks (August 17 to October 16), peaking at #7, while "What a Difference a Day Makes," by Dinah Washington, reached #8. When the first Grammy Awards were announced in May 1959, jazz was a big winner, especially in the "Pop" category - although later on the Grammy judges mostly ignored jazz.

- Album of the Year (and Best Arrangement): The Music from Peter Gunn, by Henry Mancini

Vocal Performance, Female: Ella Fitzgerald for the Irving Berlin Songbook.

Vocal Performance, Female: Ella Fitzgerald for the Irving Berlin Songbook.- Best Performance by a Vocal Group: Louis Prima and Keely Smith for "That Old Black Magic."

- Best Performance by a Dance Band: Count Basie for Basie.

- Best Performance by an Orchestra: Billy May for Billy May's Big Fat Brass.

- Best Performance, Individual (Jazz category): Ella Fitzgerald for The Duke Ellington Songbook.

For records released in 1959, the 1960 Grammy awards were also jazz-centered:

- Record of the Year (and Best New Artist): Bobby Darin for "Mack the Knife."

- Album of the Year (and Best Arrangements): Billy May for Frank Sinatra's

Come Dance With Me.

Come Dance With Me. - Best R&B Performance: Dinah Washington for "What a Difference a Day Makes."

- Best Musical Composition (also Best Sound Track and Best Performance by a Dance Band): Duke Ellington for the Anatomy of a Murder soundtrack.

Speaking of movie soundtracks, 1959 was the year that jazz scores expanded from jazz-influenced composers like Alex North, Elmer Bernstein and Henry Mancini to pure jazz artists like Duke Ellington, Gerry Mulligan and John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

In late 1958Johnny Mandel scored and a band led by Mulligan played in I Want to Live, followed by Duke Ellington's award-winning Anatomy of a Murder score in the Otto Preminger classic, released July 1, 1959. In the fall of 1959, three more movies featuring jazz artists were released: Les Liaisons Dangereuses, featuring Art Blakey; Odds Against Tomorrow, with a score by John Lewis, and Shadows, featuring the music of Charles Mingus.

The public was mostly buying good music, too. The best-selling album of 1959 was the soundtrack from Peter Gunn, which featured top Los Angeles-based jazz musicians. For the eight years surrounding 1959, the best-selling albums in America were all Broadway soundtrack albums: My Fair Lady (#1 in 1957-58), The Sound of Music (1960), Camelot (1961), West Side Story (1962-63), Hello Dolly (1964) and Mary Poppins (1965). The record-buying public was pouring more cash into music by Lerner & Loewe, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Leonard Bernstein & Steve Sondheim, Jerry Herman and other great composers than into any single item by any rock artist - and that trend continued for nearly a decade, until 1966.

Turning back to pure jazz, here are just a few of the albums recorded in those four magic months.

Day by Day, Classic Jazz Albums Recorded from February 2 to May 31, 1959

- February 3: The Cannonball Adderley Quintet in Chicago

- February 3-10: Shorty Rogers, The Wizard of Oz and Other Harold Arlen Songs

- February 9-10: Quincy Jones begins recording Birth of a Band

- February 25: The Queen's Suite, a private recording by Duke Ellington for Queen Elizabeth II

- February 28: The Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall

- March 2: Miles Davis, Kind Of Blue (5 of 6 tracks recorded)

- March 4-5: Billie Holiday, "You Took Advantage of Me" (among her last recordings)

- March 9-10: Quincy Jones: Most tracks for Birth of a Band

- March 14, 28: Art Pepper + Eleven (also on May 12)

- March 31 and April 1: Frank Sinatra with the Red Norvo Sextet Live in Australia

- April 8-9: Blossom Dearie Sings Comden & Green

- April 9: Ben Webster & Associates

- April 14: "The Single Petal of a Rose," by Duke Ellington (part of The Queen's Suite)

- April 22: Kind Of Blue's second session: "Flamenco Sketches" and alternate take of "All Blues"

- April 22-23: Dave Brubeck, most of the Gone with the Wind Album

- April 23-29: Mel Torme & the Mel-Tones, Back in Town

- May 5: John Coltrane, Giant Steps main tracks

- May 22: Ornette Coleman, The Shape of Jazz to Come

- May 26-28: Quincy Jones, more tracks for Birth Of A Band

- May 31: Count Basie: Breakfast Dance & Barbecue

You can make a case that all forms of jazz existed side by side, in relative peace, in that one year - everything from Dixieland to avant-garde was on the record shelves under one category, Jazz. The miracle year 1959 was not only the year the music was reborn, but the year that jazz creativity reached its zenith.

©Gary Alexander, 2009.

Up here in the interior of the US Pacific Northwest, the floods have receded following the sudden snowmelt of a week ago. In this valley, the snow is gone except for the big piles scooped into the corners of parking lots. We are spared the drastic sub-zero temperatures of the midwest and east. What we have is constant fog and air just enough below freezing to apply frosted decoration to nearly everything outside.

Up here in the interior of the US Pacific Northwest, the floods have receded following the sudden snowmelt of a week ago. In this valley, the snow is gone except for the big piles scooped into the corners of parking lots. We are spared the drastic sub-zero temperatures of the midwest and east. What we have is constant fog and air just enough below freezing to apply frosted decoration to nearly everything outside.

Have a good warm weekend.

The eve of next Tuesday's inauguration of Barack Obama as the 44th president of The United States is also the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. Monday, January 19, there  will be a celebration at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C, observing both occasions. The veteran journalist Nat Hentoff uses this conjunction of historic events as a point of departure to discuss the role of jazz in giving impetus to the civil rights struggle that made possible the election of a black president. Here is one dramatic story from Hentoff's article in The Wall Street Journal:

will be a celebration at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C, observing both occasions. The veteran journalist Nat Hentoff uses this conjunction of historic events as a point of departure to discuss the role of jazz in giving impetus to the civil rights struggle that made possible the election of a black president. Here is one dramatic story from Hentoff's article in The Wall Street Journal:

will be a celebration at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C, observing both occasions. The veteran journalist Nat Hentoff uses this conjunction of historic events as a point of departure to discuss the role of jazz in giving impetus to the civil rights struggle that made possible the election of a black president. Here is one dramatic story from Hentoff's article in The Wall Street Journal:

will be a celebration at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C, observing both occasions. The veteran journalist Nat Hentoff uses this conjunction of historic events as a point of departure to discuss the role of jazz in giving impetus to the civil rights struggle that made possible the election of a black president. Here is one dramatic story from Hentoff's article in The Wall Street Journal: In his touring all-star tournament, Jazz at the Philharmonic, Norman Granz by the 1950s was conducting a war against segregated seating. Capitalizing on the large audiences JATP attracted, Granz insisted on a guarantee from promoters that there would be no "Colored" signs in the auditoriums. "The whole reason for Jazz at the Philharmonic," he said, "was to take it to places where I could break down segregation."

Here's an example of Granz in action: After renting an auditorium in Houston in the 1950s, he hired the ticket seller and laid down the terms. Then Granz personally,

before the concert, removed the signs that said WHITE TOILETS and NEGRO TOILETS. When the musicians -- Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Buddy Rich, Lester Young -- arrived, Granz watched as some white Texans objected to sitting alongside black Texans. Said the impresario: "You sit where I sit you. You don't want to sit next to a black, here's your money back."

Hentoff reflects on advances involving, among others, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Max Roach, and Brown vs. Board of Education lawyer Charles Black. He connects incidents and trends from slavery to the 1940s through today. Hentoff calls it "the largely untold story" of jazz and the civil rights movement. To read his essay, click here.

After a prolonged holiday delay, the Rifftides staff has posted new recommendations in three categories. Please see Doug's Picks in the center column.

Mike Holober & The Gotham Jazz Orchestra, Quake (Sunnyside). Pianist-composer-arranger Holober chooses not to call his large congregation a big band. His scoring justifies the term orchestra. Balancing lushness with motion in and through the horn and rhythm sections, he evokes nature; the rustling of aspens in "Quake," bird song in "Thrushes." He is equally creative in his own pieces and in reinventions of songs by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Holober's soloists, including himself, are among the best in New York.

Mike Holober & The Gotham Jazz Orchestra, Quake (Sunnyside). Pianist-composer-arranger Holober chooses not to call his large congregation a big band. His scoring justifies the term orchestra. Balancing lushness with motion in and through the horn and rhythm sections, he evokes nature; the rustling of aspens in "Quake," bird song in "Thrushes." He is equally creative in his own pieces and in reinventions of songs by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Holober's soloists, including himself, are among the best in New York.  Gene Perla, Bill''s Waltz (PM). Drummer Elvin Jones should get equal billing with Perla. The two laid down basic electric piano-and-drums tracks in 1986. Following Jones' death in 2004, Perla wrote orchetrations for the pieces. With Jones digitally present, he recorded them in 2007 with the NDR Big Band in Germany and added his own bass track in 2008. Jones drives the band, and it reacts as if he were in the studio with them. The NDR has a great day. The NDR seem to always have a great day.

Gene Perla, Bill''s Waltz (PM). Drummer Elvin Jones should get equal billing with Perla. The two laid down basic electric piano-and-drums tracks in 1986. Following Jones' death in 2004, Perla wrote orchetrations for the pieces. With Jones digitally present, he recorded them in 2007 with the NDR Big Band in Germany and added his own bass track in 2008. Jones drives the band, and it reacts as if he were in the studio with them. The NDR has a great day. The NDR seem to always have a great day.  Various, Brooklyn Jazz Underground, Volume 3 (BJU). If you have heard that Brooklyn is a hotbed of young jazz artists but haven't the foggiest idea what they are about, this compilation will give you a summary. Twenty-eight musicians in combinations from a duo to a sextet stretch your ears and the definition--if there is one--of jazz. The diversity of approaches includes a viola-bass clarinet duet that sounds like French impressionism and a fine "Body and Soul" by tenor saxophonist Jerome Sabbagh.

Various, Brooklyn Jazz Underground, Volume 3 (BJU). If you have heard that Brooklyn is a hotbed of young jazz artists but haven't the foggiest idea what they are about, this compilation will give you a summary. Twenty-eight musicians in combinations from a duo to a sextet stretch your ears and the definition--if there is one--of jazz. The diversity of approaches includes a viola-bass clarinet duet that sounds like French impressionism and a fine "Body and Soul" by tenor saxophonist Jerome Sabbagh. Rahsaan Roland Kirk Live in '63 & '67 (Jazz Icons). One of eight DVDs in the impressive Jazz Icons third release, this finds Kirk touring Europe with his arsenal of horns. It is fascinating to watch him manage tenor sax, manzello, stritch, clarinet, siren and nose whistle. The forthright music he makes is even more gripping. Pianist George Gruntz, bassist Niels Henning Ørsted-Pederson and drummer Daniel Humair are among his accompanists in Belgium, Holland and Norway. Kirk's fourteen performances include two versions of his explosve "Three For the Festival"

Rahsaan Roland Kirk Live in '63 & '67 (Jazz Icons). One of eight DVDs in the impressive Jazz Icons third release, this finds Kirk touring Europe with his arsenal of horns. It is fascinating to watch him manage tenor sax, manzello, stritch, clarinet, siren and nose whistle. The forthright music he makes is even more gripping. Pianist George Gruntz, bassist Niels Henning Ørsted-Pederson and drummer Daniel Humair are among his accompanists in Belgium, Holland and Norway. Kirk's fourteen performances include two versions of his explosve "Three For the Festival"

Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop (Vintage Classics). Cather is in a class with A.B. Guthrie, Jr. and Bernard DeVoto in her feeling for the expanse and expansiveness of early America. This tale of two French priests carving their church territory out of a resistant New Mexico is an unsurpassed collection of word pictures by one of the greatest American painters-with-language. This isn't a book about jazz? Good catch. In the credo at the top of the page, see the part about other matters.

In the second concert of their 50-stop national tour, the Blue Note 7 drew a full house Friday night at The Seasons Performance Hall in Yakima, Washington. From the opener, Horace Silver's "The Outlaw," to the encore, Bud Powell's "Dance of the Infidels," the all-star band dipped into the vast repertoire of compositions by artists who have recorded for Blue Note Records in its 70-years.

Although the Blue Note 7 have recorded one album, the little time they have spent as a unit is out of proportion to the ensemble's spirit and unified sound. Introducing Lee Morgan's "Party Time," pianist Bill Charlap talked about the importance of the blues in Blue Note's history and in the development of jazz. Then, with his customary taste and power, he proceeded to demonstrate. Trumpeter Nicholas Payton summoned up Morgan in his solo and worked through edgy harmonic ideas that alto saxophonist Steve Wilson developed through six choruses of story-telling improvisation. Peter Washington followed with the first of several impressive bass solos. The all-stars played to an audience so knowledgeable and receptive that the mere mention of a tune's composer - "Joe Henderson," "Jackie McLean," "Freddie Hubbard" -- brought applause and cheers.

Nash, Payton, Bernstein, Coltrane, Charlap, Wilson, Washington

Among the highlights: Payton and drummer Lewis Nash playing off one another's energy on Hubbard's "Hub Tones;" guitarist Peter Bernstein's brilliant solo on the same piece; Wilson's soulfulness in McLean's "Ballad for Doll;" the virtuosity and humor in Nash's long solo on Cedar Walton's "Mosaic;" the layered Renee Rosnes arrangement and tenor saxophonist Ravi Coltrane's joyful phrases in Wayne Shorter's "United;" Charlap's consistently authoritative playing throughout, at a peak on Kenny Dorham's "Escapade." The encore was sandwiched between two standing ovations.

With decades of musical material to draw on, writing for the ensemble a continuing adventure for all hands and more bus time together than any band has had since the swing era, it's going to be fascinating to hear how this group has grown when they get off the road in New York in April. By the time you read this, they have played at The Shedd in Eugene, Oregon and are headed down Interstate 5 to California. Check their itinerary to see if it includes

your town or one near it. This is a band more than worth hearing.

The unforgettable 1959 Thelonious Monk Orchestra concert at Town Hall will have a 50th anniversary recreation next month at the scene of the event in New York City. Preserved on a famous Riverside album and performed by jazz repertory orchestras everywhere, Monk's  compositions in orchestrations by Hall Overton are perennially fresh, full of ensemble performance challenges and of opportunities for soloists. Reissued every few years on LP, then on CD, the recording is a basic repertoire item, as timeless as Bach, Stravinsky or Charlie Parker.

compositions in orchestrations by Hall Overton are perennially fresh, full of ensemble performance challenges and of opportunities for soloists. Reissued every few years on LP, then on CD, the recording is a basic repertoire item, as timeless as Bach, Stravinsky or Charlie Parker.

compositions in orchestrations by Hall Overton are perennially fresh, full of ensemble performance challenges and of opportunities for soloists. Reissued every few years on LP, then on CD, the recording is a basic repertoire item, as timeless as Bach, Stravinsky or Charlie Parker.

compositions in orchestrations by Hall Overton are perennially fresh, full of ensemble performance challenges and of opportunities for soloists. Reissued every few years on LP, then on CD, the recording is a basic repertoire item, as timeless as Bach, Stravinsky or Charlie Parker.

For information about the February 26-27 concerts by two bands - Charles Tolliver's and Jason Moran's - click here. While you're on the page, scroll down to trigger audio performances of "Friday The 13th" by Tolliver's band and "Little Rootie Tootie" by Moran's at Duke University's Following Monk celebration last fall.

In this promotional but nonetheless informative, piece of video, Orrin Keepnews talks about the Town Hall concert. Keepnews was a partner in Riverside Records and oversaw the recording.

And, to save you the trouble of seeking out the second part of the Keepnews story of Monk at Town Hall, here it is. Don't be put off by the repeated introduction. It is the same on all segments of Bret Primack's Keepnews interview series:

Rifftides reader Peter Myers writes:

In your liner notes from the great Christmas present CD I received, The Art and Soul of Houston Person, you mentioned a gifted 19-year-old jazz musician who plays few standards. I wondered if you were talking about Eldar. I was looking forward to seeing him at the Clearwater, FL Jazz Holiday back in October. I came away disappointed for the same reason. He played mostly his own compositions. Brilliant though he may be, his choice of music almost boredered on semi classical. I think he played one number, "Straight, No Chaser," that was recognizable, and that you could tap your foot to. I wanted to approach him at the CD sales and signing booth and tell him, in a constructive, senior citizen way, but I did not.

No, it wasn't Eldar. it was Sam Reider, an impressively talented and tasteful young man. You can find out something about him on his MySpace page and hear him in full performances, including one standard, with the Uptown Trio. You might also take a look at a Rifftides piece posted a day or two after I listened to him and his confreres in a concert. This is the paragraph from the Person notes:

A gifted nineteen-year-old jazz musician recently told me why he and his band play few standards. With touching earnestness, he explained that people under sixty don't relate to standards and that his generation has no connection to the classic songs of the last century. He had just played a concert of compositions mostly written by him or his band members. It evidently escaped him that the audience, with a sizeable component of young people, gave its most enthusiastic response of the evening to an adventurous performance of Matt Dennis's "Everything Happens to Me." As his career progresses, it may dawn on our emerging young artist that when he provides his listeners a melody they can hold onto, they open up to him and accept considerable leeway when he goes beyond the familiar. That has been a fact of life in music at least as far back as Mozart.

As for Eldar Djangirov, the first time I heard him, in a Brubeck Institute workshop run by Roy Hargrove, I was mightily impressed. I think he was sixteen. When his records started coming

out, I heard what you're apparently alluding to, overplaying and a tendency toward pretentiousness, also reflected in his or his handlers' deciding that he should use only one name, a la Beyoncé or Liberace. That's show biz. I haven't heard Djangirov in live performance in several years and don't wish to issue a blanket criticism of a young man who has formidable technical gifts and enormous musical potential. I hope that, ultimately, he will prove to also have taste, judgment and the ability to edit himself at the keyboard. As Miles Davis and John Lewis, among many others, have pointed out, it is important to know what not to play.

Because of a digital malfunction the nature of which I am unequipped to explain, some of the pictures in the recent Rifftides archives have disappeared and been replaced by empty boxes. The artsjournal.com technical hierarchy assures me that the gremlins have been found and summarily executed, but their mischief remains until the Rifftides staff can repair it. That is a matter of one photo being restored at a time. The staff has plenty to do and will undertake restoration as time allows. If you are browsing the archive and disturbed by those ghostly frames, we offer the standard modern mea culpa in times of disaster large or small: we regret any inconvenience.

As readers of Rifftides know by now, The Wall Street Journal provides more than financial news and market reports. The newspaper has a Leisure And Arts section with extensive, varied, informed cultural coverage. It includes writing about music by several contributors. I am happy to be one on occasion. In today's WSJ, Nat Hentoff brings together his friendship with Dizzy Gillespie and the need to care for sick or injured musicians with little or no health insurance.

...dying of pancreatic cancer, Dizzy, who had health insurance, said to Francis Forte, his oncologist, and himself a jazz guitarist: "I can't give you any money, but I can let you use my name. Promise you'll help musicians less fortunate than I am." That was the Dizzy I knew, regarded by his sidemen as a teacher and mentor. From that conversation began the Dizzy Gillespie Memorial Fund and the Dizzy Gillespie Cancer Institute at the hospital. By now more than a thousand jazz musicians unable to pay have received a full range of medical and surgical care by Dr. Forte and a network of more than 50 physicians in various specialties, financed by the hospital and donations.To read the whole thing, go here.

Nat's piece reminded me that Dizzy died fifteen years ago this week. When I got the news, I wrote an op-ed piece. It ran in The Los Angeles Times on January 8, 1993 under the headline, "Our Friend Dizzy."

As I write this, Dizzy Gillespie has been dead a few hours and KLON-FM is playing his recordings one after another. I'm sipping a red wine as close as I could find to the one he and I drank a lot of on a fall afternoon of listening and laughter in 1962 in his hotel room in Cleveland. I'm trying to summon the feelings of desolation and loss requisite when a friend and idol dies.But there's so much joy in his music, so much of his irrepressible spirit, so much of his foxy wisdom and humor, that John Birks Gillespie won't allow me to sustain grief for more than a few seconds. At the other end of the phone line, up in Ojai, Gene Lees tells me that after someone called with the news, he stopped working, couldn't write; a man who's written yards about Birks, who wrote a book called Waiting For Dizzy.

I stare out into the rain, thinking about the next to last time I saw Diz in Los Angeles, backstage at the Universal Amphitheater following a middling concert by his quintet He was standing against a wall, relaxed, leaning on a broomstick loosely covered with bottlecaps, his famous rhythmstick. He shrugged and grinned. The shrug and the grin said, "What the hell, you can't win 'em all." I think about the day I was walking down Broadway in New York and heard his unmistakable voice from the midst of the traffic roar. A car pulled up to the curb. Dizzy got out, bowed low and said, "Get in, please, you're coming with us." And we spent a crazy hour touring midtown Manhattan while Birks entertained everyone in and within hearing distance of the car with his descriptions of people, buildings and city life. Over the years, I had a least a dozen such experiences with Dizzy, and each of them had the warmth, spontaneity and unpredictability of his music. Multiply that by the hundreds, probably thousands, of people he treated with the same generosity and affection, and you begin to comprehend the dimesions of love and pleasure he created not only with his music but his being.

The last time I saw him in L.A., at the Greek Theater, he had just led his big band through two hours of perfection. There were moments that night when his trumpet had the glory, the impossible virtuosity, of the strongest performances of his youth. This time backstage there was a bear hug and a little dance and he said, "Rams, you dog, if I'd known you were out there, I'd have tried to play something."

Daz McSkiven Voutzoroony, Slim Gaillard called him. Young trumpet players called him God. "It's all in Arbans," all in the famous trumpet exercise book, he used to say when he was asked about his technique. Right. And everything William Faulkner needed was in Webster's dictionary. Birks and Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Kenny Clarke, Oscar Pettiford, and a few others transformed jazz in the 1940s and the power of their transformation influenced American music in all of its aspects, from pop hits and supermarket Muzak to the tonal values and breathing habits of symphony trumpet sections. Gillespie's mastery of rhythm has been an inspiration to players of every instrument, including drums. Show me a jazz drummer born after 1920 who doesn't worship Diz and I'll leave you to listen to some mediocre drumming.

Driving home through the storm tonight, I played a new compact disc by a group of musicians including the young trumpeter Tom Williams. As Williams blew phrases Clifford Brown developed after hearing Fats Navarro, who learned from Dizzy, who studied Roy Eldridge, Louis Armstrong's great successor, I reflected on the "end of an era" clichés we hear when a great person dies. The end of an era, possibly. But not the end of a tradition. Thanks, Birks. See you in the land of Oobladee.

If you are at all disturbed by what we human beings are doing to one another in Israel, the Gaza Strip, Iraq, Afghanistan, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Georgia, Russia, Colombia, the Koreas (sorry if I  left out your favorite), spend a few minutes with a man who died 98 years ago. I wish I'd thought of this, but my artsjournal.com colleague Terry Teachout gets credit for recalling a classic piece of theater--and a great American philosopher. To see that man revived on Terry's blog, click here.

left out your favorite), spend a few minutes with a man who died 98 years ago. I wish I'd thought of this, but my artsjournal.com colleague Terry Teachout gets credit for recalling a classic piece of theater--and a great American philosopher. To see that man revived on Terry's blog, click here.

left out your favorite), spend a few minutes with a man who died 98 years ago. I wish I'd thought of this, but my artsjournal.com colleague Terry Teachout gets credit for recalling a classic piece of theater--and a great American philosopher. To see that man revived on Terry's blog, click here.

left out your favorite), spend a few minutes with a man who died 98 years ago. I wish I'd thought of this, but my artsjournal.com colleague Terry Teachout gets credit for recalling a classic piece of theater--and a great American philosopher. To see that man revived on Terry's blog, click here.

Today is the 70th anniversary of Blue Note Records, and -- what a coincidence -- I have at hand an advance CD by the Blue Note 7. That is the all-star band of Blue Note artists on  the verge of a three months tour to celebrate the longevity of a company that has made a difference in music. The tour opens Thursday evening at the Moore Theater in Seattle. Friday, the band will be across the Cascade mountains in Yakima, Washington, at The Seasons Performance Hall. I will be there, listening intently after having the pleasure of introducing the band. It is my intention to give you a report reasonably soon after the event. For a list of cities and dates of the tour, go here.

the verge of a three months tour to celebrate the longevity of a company that has made a difference in music. The tour opens Thursday evening at the Moore Theater in Seattle. Friday, the band will be across the Cascade mountains in Yakima, Washington, at The Seasons Performance Hall. I will be there, listening intently after having the pleasure of introducing the band. It is my intention to give you a report reasonably soon after the event. For a list of cities and dates of the tour, go here.

With pianist Bill Charlap at the helm, the other all-stars are guitarist Peter Bernstein, tenor saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, drummer Lewis Nash, trumpeter Nicholas Payton, bassist Peter Washington and alto saxophonist Steve Wilson--a cross-section of the cream of the modern jazz mainstream. Their new CD, titled Mosaic, includes that Cedar Walton composition and

pieces by Horace Silver, Herbie Hancock, Thelonious Monk and other musicians associated with Blue Note through the years. A companion disc, contains the original recordings of the pieces from the Blue Note archive by Monk, Hancock, Joe Henderson, Art Blakey, McCoy Tyner, Grant Green, Horace Silver and Bobby Hutcherson.

As I have emphasized here on more than one occasion, medium-sized bands can provide some of the greatest satisfactions in jazz. The arrangements of eight modern classics by members of the band and pianist Renee Rosnes (Mrs. Charlap) add to the successes in the genre. They respect the originals while introducing new touches--a bit of note-bending in the line of Hancock's "Dolphin Dance," the full-bodied orchestration of Grant Green's theme in "Idle Moments," a feeling of suspended animation leading into the main section of Joe Henderson's "Inner Urge." As for soloists, these are some of the best of their generation. They perform accordingly. Payton

impresses me more with the content of his improvisation on this record than anything I have heard from him in years. His solos here have the story-telling quality that separates first-tier jazz soloists from the herd. Charlap achieved that literary attribute long ago, but

on some of these tracks he gets into an edginess, particularly on Monk's "Criss-Cross," that adds an element he has seldom displayed. Maybe it's Monk's spirit that brings out chance-taking; Payton and Wilson also dive in with abandon on this piece.

Well, it's all good, and I look forward to hearing what the Blue Note 7 have added to the repertoire since they made this album last year.

Dena DeRose: Live At Jazz Standard, Volume Two (MaxJazz). Spontaneity and a sense of discovery continue in this second set by DeRose and her trio at the New York club. She, bassist Martin Wind and drummer Matt Wilson connect with one another and with an enthusiastic audience. The connection comes by way of taste, musicianship and a sense of shared enjoyment -- outright fun, in fact. As in volume one, she concentrates on standard songs, but this time she includes three that are seldom done.

DeRose has kept "The Ruby and the Pearl" in her repertoire for a dozen years or more. She recorded it in her first album in 1996 and has deepened not only her interpretation of the lyric but also her improvisation. The track contains the first of several instances of DeRose's vocalizing in unison with her single-note lines on the piano, something she does superlatively in the tradition of Joe Mooney. The fun reaches its apogee in "Laughing at Life," which DeRose gives a straightforward treatment without the edge of irony in Billie Holiday's version. Following her first vocal chorus, she begins riffing on a phrase and the trio turns the piece into a virtual blues, to the hilarity of all concerned. She brings to "I Can't Escape From You" a melancholy reading enhanced by Wilson's subtle cymbal splashes.

Derose plays a reflective out-of-tempo introduction before she takes "In Your Own Sweet Way" into a comfortable ¾ swing wth a fine bass solo by Wind. It has a chorus by DeRose that makes me wonder why she isn't more frequently mentioned as a leading piano soloist. It is the only non-vocal track on the CD. As in his work in the trios of two other pianists, Bill Mays and Denny Zeitlin, Wilson keeps the attention of his colleagues and his listeners, layering in little packages of rhythmic surprise as he lays down perfect time. "When Lights Are Low," "Detour Ahead," "I Fall in Love Too Easily" and "We'll Be Together Again" round out the album, all at a high level of satisfaction in this welcome recording.

This spring will see the release on DVD of a documentary film that dramatizes the degree to which we're all in this troubled world together. The film uses music to make that point and the further one that music can help heal our differences. Its producer, Mark Johnson, took video and sound equipment around the world. He spent ten years filming musicians and singers in South Africa, Moscow, New Orleans, Tibet and scores of other places, then melding their work into Playing For Change: Peace Through Music. I have seen only this clip of the documentary and was moved by it.

For more about Johnson and his film, go here to see a program Bill Moyers did in October on PBS television.

A concert in memory of Richard M. Sudhalter, the distinguished jazz musician, historian, biographer, and critic, will be held on Monday, January 12, at St. Peter's Lutheran Church,  619 Lexington Avenue at 54th Street, New York City, from seven to ten p.m.

Sudhalter died last September. For a Rifftides remembrance and appreciation of this extraordinary man, go here.

619 Lexington Avenue at 54th Street, New York City, from seven to ten p.m.

Sudhalter died last September. For a Rifftides remembrance and appreciation of this extraordinary man, go here.

619 Lexington Avenue at 54th Street, New York City, from seven to ten p.m.

Sudhalter died last September. For a Rifftides remembrance and appreciation of this extraordinary man, go here.

619 Lexington Avenue at 54th Street, New York City, from seven to ten p.m.

Sudhalter died last September. For a Rifftides remembrance and appreciation of this extraordinary man, go here.

The list of musicians scheduled to perform includes Howard Alden, Donna Byrne, James Chirillo, Bill Crow, Armen Donelian, Bob Dorough, Paquito D'Rivera, Jim Ferguson, Carol Fredette, Marty Grosz, Sy Johnson, Dick Katz, Bill Kirchner, Steve Kuhn, Dan Levinson, Boots Maleson, Marian McPartland, Ray Mosca, Joe Muranyi, Sam Parkins, Ed Polcer, Loren Schoenberg, Daryl Sherman, Nancy Stearns, Carol Sudhalter, Ronny Whyte, Jackie Williams, and Marshall Wood.

Between performances, Albert Haim, Dan Morgenstern, Pat Phillips, and Daryl Sherman will talk about Dick. Terry Teachout will play some of his favorite records.

The concert is open to the public.

Sudhalter was the ranking Bix Beiderbecke expert among jazz musicians of the second half of the twentieth century and the first years of this one. He wrote the definitive Beiderbecke biography and was a student and close friend of cornetist Jimmy McPartland, who succeeded Bix in the Wolverines. Sudhalter appeared more than once on Marian McPartland's Piano Jazz program on National Public Radio to discuss Beiderbecke and play duets with Ms. McPartland on tunes Bix wrote. To hear one such program, from 2000, go here and click on "Listen Now."

Freddie Hubbard's family has released information about his funeral service.

1:00 PM, Tuesday, January 6, 2009 -- viewing from 11 AM

Faithful Central Bible Church's Tabernacle

321 North Eucalyptus Avenue

Inglewood, CA 90301

Faithful Central Bible Church's Tabernacle

321 North Eucalyptus Avenue

Inglewood, CA 90301

The trumpeter died December 29. For a Rifftides appreciation of his career, go here.

Bill Ramsay is a veteran saxophonist widely admired in jazz circles

across the US but little known to the public outside the Pacific Northwest.

Accomplished on alto and baritone saxes,he co-leads the Ramsay-Kleeb band and

is the baritone sparkplug of the Seattle Repertory Jazz Orchestra. Ramsay has

been a first-call sub on the Count Basie band for decades. His good-natured jousting partnership

with tenor saxophonist Pete Christlieb never fails to produce hard swing and spontaneous

standup comedy.

Repertory Jazz Orchestra. Ramsay has

been a first-call sub on the Count Basie band for decades. His good-natured jousting partnership

with tenor saxophonist Pete Christlieb never fails to produce hard swing and spontaneous

standup comedy.

Repertory Jazz Orchestra. Ramsay has

been a first-call sub on the Count Basie band for decades. His good-natured jousting partnership

with tenor saxophonist Pete Christlieb never fails to produce hard swing and spontaneous

standup comedy.

Repertory Jazz Orchestra. Ramsay has

been a first-call sub on the Count Basie band for decades. His good-natured jousting partnership

with tenor saxophonist Pete Christlieb never fails to produce hard swing and spontaneous

standup comedy.Ramsay celebrates his 80th birthday this month. Jim Wilke will observe the occasion on his Jazz Northwest radio program on Sunday, January 4 at 1:00 p.m. Pacific time, 4:00 p.m. Eastern. Wilke will include previously unissued music by Ramsay's big band, recorded in 1961. To hear the program in the Seattle-Tacoma area, tune in KPLU at 88.5 FM. To hear it on the internet, go here.

Ramsay and I are not related -- except by mutual interests. Whenever I encounter him, he tells me to correct the spelling of my last name and I tell him to correct the spelling of his.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

About Last Night

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Artful Manager

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

blog riley

rock culture approximately

rock culture approximately

critical difference

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Dewey21C

Richard Kessler on arts education

Richard Kessler on arts education

diacritical

Douglas McLennan's blog

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dog Days

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Flyover

Art from the American Outback

Art from the American Outback

lies like truth

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world