November 28, 2006

Book 2.0

Episode 15: Glorious Noise

In

recent episodes:

I've

been talking about the origins of the classical music world as we know it

today. In episodes seven,

eight,

and nine,

I described the music world of the 18th century, when composers we now call

classical were active -- Bach, Handel, Vivaldi, Haydn, Mozart -- were active,

but the concept of classical music didn't exist. Music wasn't considered a

deeply serious art, and musical performances were mostly entertainment. Almost

all the pieces played were new. People talked while the music played, and

reacted loudly, clapping and cheering when they heard something they liked. The

musicians often improvised, to an extent we can barely imagine today.

But

then, beginning at the start of the 19th century, things changed. The concept

of classical music emerged, as I discussed in episodes

10, 11, and 12. The romantics thought music was the highest of the arts,

because it somehow expressed the deepest truths. That, of course, made it

possible to urge that music be listened to in reverent silence, and to make a

distinction between artistic music and music that served only as entertainment.

Classical music -- Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, plus a few earlier composers

like Handel and Bach whom connoisseurs were aware of, and also living composers

like Schumann and Mendelssohn, who consciously based their music on classical

models -- was opposed to popular music, which was Liszt and Rossini, or more

generally opera, and anything played by the spectacular and newly fashionable

virtuosi.

Eventually

classical and popular music (as they were defined back then) started to blend,

so that even Italian opera -- the height of popular music in the 19th century --

began to be considered classical. By the end of the 19th century, most of the

pieces played were old, and musicians rarely improvised, which brings us very

nearly to where we are in classical music today. For

much more on all of this, read the episodes, or else

the longer summary that introduced episode

13.

In that episode, I moved on to something else that helped create the classical music world we now know -- the rise of modernism, which (as I'm about to say in the current episode) boxed new classical music into an isolated corner it might only recently have started to move out of. This happened in the 20th century. But before discussing that, I wanted to show how in the 1890s, new music still could be healthy and vital, even if most of the music in the concert hall was old. That's what episode 13 was about.

And

then we moved on to hard-core modernism. In episode

14 I rather obstreperously argued that modernism -- which might briefly be

defined as the musical equivalent of abstract art -- became (as abstract art

never did in the visual arts world) in some ways an oppressive force. It

started wonderfully (as I'll show in the next episode), but its function,

inside the classical music world, in the end grew almost pathological. Part of

that pathology was that it was forced on an unwilling audience, and another

part was that it never found any lasting support among artists in other fields

and intellectuals.

So

by the end of its reign -- more or less around 1980, the end of the period when

it had more prestige, among classical music leaders, than new classical music

of any other kind --modernist music had accomplished something almost

unthinkable. Because people came to expect that all new pieces would be

modernist, new classical music itself -- the entire enterprise of writing new

classical music -- developed a bad odor inside the classical music world.

Audiences almost always cringed when a new piece showed up on a concert

program. And since modernist music also, as I've said, divorced itself from

artistic life outside the classical music world, it ended up isolating new

classical music from nearly everyone. This -- as should hardly need saying -- was

a disaster for classical music as an art form.

Here

I added some history about Stravinsky --how, after his initial successes (with

pieces like The Rite of Spring, he

came to embody the isolation of musical modernism. He became one of the most

famous people in classical music, and for years supported himself by conducting

his own music with many orchestras. But by and large the only time his new pieces was performed was when he himself conducted them.

Toward the end of his life, he was a celebrity even outside classical music

(Frank Sinatra once asked for his autograph!), but the atonal pieces he then

wrote were hardly ever done by anybody. The world's greatest composer, by

general consent the only living member of the classical pantheon, now had a

career that consisted largely of celebrity and prestige.

I'm

not saying that modernist music is pathological, and certainly not that

modernist composers, from Schoenberg to Pierre Boulez, have been. Nor am I

saying that I myself don't like modernist music. As I wrote episode 14, I

listened to pieces by Schoenberg and Webern, two composers who were founding

fathers of modernism, and whose modernist music (again, think of a musical

equivalent of abstract art) has never caught on inside the concert hall. And

one thing that comes across to me, across the gap of generations, is a kind of

wistfulness, as if Schoenberg and Webern lived right on the surface of their

skin, eagerly hoping that somebody would listen to them. This,

despite the cloistered musical procedures -- a bristling collection of them --

that both composers used.

At

this point, I described the 12-tone system, and I hope I brought it alive,

something -- I don't mean to be immodest, but this is the truth -- I've never

seen done in print. Please read

the episode for this! And also for some evocations of things I love in

Webern, including this:

At the start of [his Symphony, Op. 21], the

music [seems] to unfold spatially, as well as through a span of time. Then when something new happens, the sound

is quietly transforming, as if a new light, in some new color, had started

shining in what otherwise might be unchanging space.

If

you look closely at his scores, you sometimes see things that are almost

metaphysical. In [his Piano Variations]...there's an accelerando (as a musician

would put it) written over a series of rests. Or, in plain English, Webern

wants the music to speed up during a silence! This is a sweet, ineffable, but

also very deep impulse, one that comes from a consciousness that every moment

in a piece of music glows with light, even silences.

And

modernist music was deeply necessary. Life was being disrupted when these

pieces started to be written. World War I killed millions. In its wake came

revolutions, and economic madnesss. People started to

understand -- and express -- the power of unconscious impulses. Sexual feelings

surged to the surface. Einstein displaced the certainly of space and time. Art

turned abstract, or even -- with the rise of dada -- random and deliberately

meaningless. Sounds and images from non-western cultures entered common

consciousness. The pounding growth of cities made the countryside for many

people just a memory. Machines were everywhere. People talked about a new

"machine age."

How

could music not reflect all this? The pathology, then, might have been in the

classical music world, which -- rejecting the modern age -- hung on (and still hangs

on) to comforting sounds that evoke an earlier, more peaceful way of life.

And

when modernism emerged, it could be innocent and eager. Think of Schoenberg

after he'd fled the Nazis and settled in America, making a grateful speech in

1947 to the National Institute of Arts and Letters:

Personally I had the feeling as if I had fallen into an ocean of

boiling water, and not knowing how to swim or to get out in another manner, I

tried with my legs and arms as best as I could.

I do not know what saved me; why I was not drowned or cooked alive. I

have perhaps only one merit: I never gave up! But how could I give up in the

middle of an ocean....

How can anyone not feel sympathy for such a man, or not want to hear

his work?

And

then there's the famous -- or rather infamous -- explosion from Pierre Boulez in

1952, who (as he worked with a musical language that derived from Schoenberg)

threw this in everybody's face:

...any musician who has not experienced -- I do not say understood, but

truly experienced -- the necessity of the dodecaphonic [12-tone] language is

USELESS.

People

find Boulez's statement threatening. But he was only in his 20s -- really just a

kid -- and his rants were the overflow of vast enthusiasm. How much power did he

really have?

***

Loonacied! Marterdyed!! Madwakemiherculossed!!!

Judascessed!!!! Pairaskivvymenassed!!!!!

Luredogged!!!!!!

-- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

There's a romantic view of modernism, or maybe just a romantic view of art, that goes something like this. Intrepid pioneers seek visionary new horizons. They make art that hardly anybody understands at first. But after a while their work catches on, and they join the pantheon of the greats.

Who in classical music would embody that? Beethoven, maybe (though he didn't alienate all that many people; still, his last quartets were considered half-insane for many years). Wagner. And, among the modernists, Stravinsky, because the premiere of Le sacre du printemps provides such a comforting version of the old romantic story.

The premiere, as everybody knows, was a failure, and also some kind of cataclysm. Both the music and the awkward, shocking, ballet it was written for upset many people, and the premiere was noisy, to say the least:

It was only by straining our ears amid an indescribable racket [one observer wrote] that we could, painfully, get some rough idea of the new work, prevented from hearing it as much by its defenders as by its attackers.

A member of the orchestra later talked about something that happened in rehearsal:

There is an incident I remember well. When we came to a place where all the brass instruments, in a gigantic fortissimo, produced such an offending conglomeration that the whole orchestra broke down in a spontaneous nervous laugh and stopped playing. But Stravinsky jumped out of his seat, furious, running to the piano and saying, "Gentlemen, you do not have to laugh. I know what I wrote," and he started to play the awful passage [on the piano, presumably], reestablishing order.

Though my favorite account comes from a later performance, the first concert performance of the piece. Alfredo Casella, a leading Italian composer of the next generation, was there, and notes in his memoirs that

We were afraid that the scandals of the previous year would be repeated. Instead, the new performance, free of the perilous choreography of Nijinksy and held to the orchestra alone, achieved a delirious success.

But there was one person, at least, who didn't like it. This was the aged Camille Saint-Saëns, the leading French conservative composer. Not that Saint-Saëns heard much of the piece; all he could take, apparently, was the opening bassoon solo, which is higher and more perilous than anything ever written before for the bassoon, and suggests -- with its strained, raw, yearning -- some kind of pagan wail. (Or that's how it must have sounded at the time. Bassoonists can play it smoothly now, which maybe isn't what Strvainsky expected.)

Here's how Casella tells the story:

I was sitting in a box with some friends as the performance was about to begin. The door opened, and with surprise I saw the venerable Saint-Saëns enter. He refused to sit in front of us and, hermetically wrapped in furs, curled himself up at the back of the box, looking for all the world like the patient who waits in the dentist's antechamber, to have a tooth pulled. The prelude began, and when Saint-Saëns heard the first note of that solo whose quality is so strange and primitive, he asked me, terrified: "What is that instrument?" When I answered calmly, "Master, it's a bassoon," he made the dry rebuttal in his nasal and unpleasant voice, "That's not true!" and went out banging the door, cursing those crazy modernists who succeeded even in making unrecognizable such a peaceful instrument...

In my last episode, I listed some of the ingredients of

modernism, among them the disruption of everyday life, a surge of unconscious

impulses, pounding noise, and sounds and images from non-western cultures. All

these figured in Le sacre

du printemps, which (as I've said) depicts a

terrifying human sacrifice. The scene is ancient, pagan

In our time, of course, the piece has been domesticated. One sign of this was an exercise the members of an orchestra (not one of our country's largest, but not one of our smallest, either) did, in an attempt to find ways to introduce more people to The Rite of Spring, as the piece is known in English. Of course they weren't trying to get anyone to accept its modernity; they were simply trying to bring a new audience to all of classical music, and they used The Rite as their exercise, as easily as they might also have used Mozart. Suppose, they said, people made up their own rites of spring? Then they'd move one step closer to the piece. And what would those rites be? Well, let's see...people could press flowers in a scrapbook...

Forgotten, evidently, was the stark and shocking central point (which sometimes comes to life, even now, as it does in a desperate version of the ballet by the searing German choreographer Pina Bausch) -- the rite here is human sacrifice. But if the piece is now domesticated, maybe we'd better overlook that. This, of course, is yet another example of how classical masterworks (precisely because we accept them as masterworks) lose their content. (Because they're masterworks, we're expected to adore them as sacred objects. How could we do that if they shocked us?)

But it's also fascinating to see how modernism can be gutted. The bracing noise, for instance, that was so notably a part of it -- this tends to disappear, both for people who don't like modernist work (for whom the noise becomes nothing more than what they think is an ugly kind of music), but even more notably for people who love modernism, who hear the noise as just another kind of harmony, more complex, maybe, than the harmony (the chords) we hear in more melodic music, but in principle no different. The noise disappears.

So what other modernist music -- or "modern music," as it was called back then -- upset people in the early years of the 20th century?

Well, there was Schoenberg, who, much later, became the poster demon (so to speak) of unpleasant musical modernism. He and Stravinsky came to be thought of as opposites, the two poles of modern music, Stravinsky the rhythmic, unemotional and neoclassic pole, and Schoenberg the angst-ly pole, his music smeared with unrelenting ugly dissonance. That last description is of course a caricature, written from the point of view of people who couldn't accept what Schoenberg wrote. If they had been painters, Stravinsky might have been Picasso (very approximately), and Schoenberg very well could have been Kandinsky, who (as we'll see) was his friend, and artistic co-conspirator.

Both men, for whatever this is worth, were very short. Both

at one time lived in

Schoenberg's problem -- if he wanted Stravinsky's fame (which very likely he didn't) -0- might have been that he never wrote anything as gaudy or convulsive as The Rite of Spring. He first got known as the composer of a huge romantic work, Gurrelieder, in a style that didn't hold much current interest as the 20th century progressed. His signature modern work, Pierrot Lunaire, sounds wistful (a word I find I keep on using to describe his work), and just a little drunk, spectacularly wrought from any purely musical point of view, but also introverted and just a bit obscure. It's written for just five instruments, and a singer, who doesn't quite sing, and doesn't quite speak, but instead is told to somehow stay in a neverland halfway between song and speech, instructions that lead most singers to swoop and moan in a way that easily can sound mannered, odd, and artificial.

Maybe this piece (which premiered in 1912, a year before The Rite of Spring) has some connection to edgy German cabaret, but it's hardly designed for popular consumption. It briefly overwhelmed Stravinsky, though, who wrote a set of little songs -- called Three Japanese Lyrics -- under its influence, and moved on to other things. But it's interesting, maybe, that Stravinsky situated his Schoenberg-related piece in some version of Japan (far away from home, in other words, both from his original home in Russia, or his adopted home in France), because when Schoenberg made his first decisive move into new aesthetic territory, he said he'd gone to another planet.

This happened in his second string quartet, which premiered in 1908. Earlier Schoenberg had gotten in trouble with a string sextet called Transfigured Night, a partly troubled, partly ecstatic piece (already we're in the extreme emotions that modernism thrived on), which notoriously sounded to one critic as if someone had taken music from Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde, and smeared the ink on the written score. Of course, Tristan itself, when it was first unveiled in the 1860s, had seemed incomprehensible to many people (as if, perhaps, someone had taken some established 19th century composer -- Liszt? Schumann? even Beethoven? -- and smeared the ink on the written score. So the process Schoenberg appeared to be starting was already underway.

The second string quartet went further, though. Transfigured Night is easy for us to hear now; the string quartet isn't, and has never really entered the standard classical repertory. At the end -- in its final movement -- it turns atonal, a technical term that means many things to many people, but certainly signifies that Schoenberg had abandoned some normal ways of writing music. An atonal piece (which, technically speaking, isn't in any key, and uses highly dissonant chords, for the most part avoiding simple and familiar ones) can seem to drift away from any anchor, any resting point, any moment when a listener can say (paraphrasing Goethe's famous line in Faust), "Stop, this is beautiful!"

I myself don't have that problem, since I'm used to atonal music; I have trouble, in fact, hearing where the line that separates tonal writing from atonality is crossed. It's all familiar to me. But others (and I sympathize with them) can't say the same; atonality hasn't caught on, except in film scores, where it's easily accepted as an underscoring, musically, for angst and uneasiness. And Schoenberg seemed to know he'd crossed a line, since when the music drifts to atonality, he has a singer (who'd already joined the instrumentalists of the string quartet in the movement just before) sing his musical setting of a poem by Stefan Georg, which starts, "I breathe the air of other planets." (I've put the full text, for anyone who's curious, as an addendum, after the end of this episode.)

But the audience, it seems, couldn't breathe that air. As Schoenberg later remembered,

My second string quartet caused at

its first performance in

Astonishingly the first movement passed without any reaction, neither for nor against. But after the first measures of the second movement the greater part of the audience started to laugh and did not cease to disturb the performance during the third movement "Litanei" ["Litany"] (in the form of variations) and the fourth movement "Entrückung" ["Rapture"]. It was very embarrassing for the Rosé Quartet and the singer, the great Mme. Marie Gutheil-Schoder. But at the end of this fourth movement a remarkable thing happened. After the singer ceases there comes a long coda played by the string quartet alone. While, as before mentioned, the audience failed to respect even a singing lady [how old-fashioned this sounds!], this coda was accepted without any audible disturbance. Perhaps even my enemies and adversaries might have felt something here?

Another key Schoenberg piece from this period was Erwartung, dating from 1909, whose title is inadequately translated as "Expectation" or "Anticipation"; more neutrally, it might simply be "Awaiting," though as a noun that unfortunately isn't an English word. Erwartung is (as Schoenberg labeled it) a "monodrama," an opera with just one character, a nameless woman about whom we know almost nothing, except that she's wandering in a forest of anxiety, with overtones of love and murder, and that her voice shakes and screams against a huge and troubled orchestra. Modernist angst, quite plainly, fills the work; Freudians could burrow usefully inside it. But this piece, too, like the string quartet, hovers just past the edge of the standard classical repertoire, depriving us (because we almost never hear the piece) of a priceless, quite affecting taste of the emotions that fed the last century.

Schoenberg himself eventually retreated into his own Society

for Private Musical Performances, which isn't to say he didn't also function in

the wider musical world; he just didn't do so well there. Eventually (fleeing

the Nazis) he settled in

And as we'll see, he retreated from the seethe of Erwartung into a search for discipline and order. Which brings me -- "by a commodius vicus of recirculation," as Joyce wrote on the first page of Finnegans Wake -- back to the gutting of modernist noise. Though first, recirculating again, I want to talk a little (and with some wistful nostalgia for a time before I was born) about how that noise was once celebrated. I could even start with Schoenberg, who later became an apostle of discipline and order. (Hoping, as he said, to ensure the superiority of German music for the next thousand years, but let that go.) In 1918, he seemed to want something wild. Here are some fragments from a kind of artistic credo he outlined in a letter to Ferrucio Busoni in 1918:

I strive for: complete liberation from all forms

from all symbols

of cohesion and

of logic

No order or discipline for him! And note that he wrote this down almost as a poem, with all kinds of urgent indented lines:

And the results I wish for:

no stylized and sterile protracted emotion.

People are not like that:

it is impossible for a person to have only one sensation at a time.

One has thousands simultaneously. And these thousands can no more readily be added together than an apple and a pear. They go their own ways.

And this variegation, this multifariousness, this illogicality which our senses demonstrate, the illogicality presented by their interactions, set forth by some mounting rush of blood, by some reaction of the senses or the nerves, this I should like to have in my music.

A mounting rush of blood! Has anyone ever described 12-tone music in tones anything like that? (Well, Stockhausen --working a generation after Schoenberg, just after World War II - did call the serial music he was writing "a universe in perpetual expansion." Serial music was the eager extrapolation of 12-tone writing into many more dimensions; those, too, were exciting times.)

But it's in

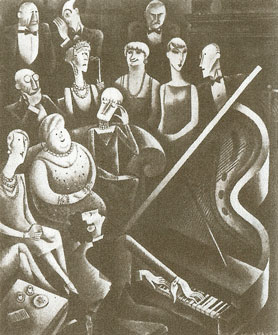

The 1920s Vanity Fair ran cartoons about "modern music," including this one, which ran in 1929, titled "A Salon Recital of Modern Music: One of Those Awesomely Elegant Evenings Which [High] Society Has to Suffer":

From which we learn that society ladies like those in this

drawing hosted "modern music" recitals often enough to get laughed at. (Compare

that, maybe, to the "radical chic" of the 1960s.) An article in The New Yorker "sarcastically pointed

out [as Carol Oja says in her book Making Music Modern] that women were

giving up the

Dane Rudhyar, a spiritually inclined composer (who later gave up music and became an astrologer), evolved theories about the spiritual meaning of dissonance. He wasn't alone in this; people really did talk about the cosmic meaning of dissonance. (Including Charles Ives, the greatest and most comprehensive American composer of that time, though he worked mostly in solitude.) Masses of notes, all sounding together, seemed to evoke masses of people, or the hugeness of immortal souls. Dissonance -- the noisier the better -- liberated music. Music, Rudhyar wrote,

is not based...on melodic themes and the like. Rather it is founded on the building of resonances or complex harmonies which are like vital seed-tones germinating, sprouting into vast trees of harmonies. It deals with Energies, not with so-called Form.

Rudhyar also said that a new composer

deals with living matter and no longer with patterns of notes. He takes with his powerful hand the throbbing instrumental matter, kneeds [sic] it into the image of his own living human Soul.

And:

Dissonant music is thus the music of true and spiritual Democracy; the music of universal brotherhoods; music of Free Souls, not of personalities. It abolishes tonalities, exactly as the real Buddhistic Reformation abolished castes into the Brotherhood of Monks.

(All these quotes come from Carol Oja's research.)

On a more earthly plane, composers started writing noisy

music about machines, and it started showing up on

This is the label from a British release, but the recording

was available in

We could even add Gershwin to this list, because An American in Paris bursts happily with the noise of Parisian traffic, with automobile horns added to the orchestra for an extra touch of noisy realism. But the king of noise in New York was George Antheil, a composer who titled his autobiography Bad Boy of Music, who'd written three machine-age piano sonatas -- The Airplane, Sonata Sauvage [Savage Sonata], and Death of Machines --and in 1927 brought his tumultuous Ballet Mécanique [Mechanical Ballet] to Carnegie Hall. There was endless hype, eagerly spread by Antheil himself, and even an extra attraction, with a pop culture twist: the W. C. Handy Orchestra played Antheil's Jazz Symphony. Handy, of course, was the legendary "father of the blues," though of course he didn't invent blues, but just popularized the form, and wrote some of the most famous blues songs, including "St. Louis Blues." His orchestra was a big attraction (though at Carnegie Hall, someone else conducted it; Handy wasn't a good enough conductor to handle Antheil's classical complexities).

But the Ballet Méchanique was the main attraction, "the first piece of music," Antheil had said two years before, "that has been composed OUT OF and FOR machines, ON EARTH." (Those are his capital letters.) The music, he went on, was

Scored for countless numbes of player pianos. All percussive. Like machines. All efficiency. NO LOVE. Written without sympathy. Written cold as an army operates. Revolutionary as nothing has been revolutionary.

(You see what I mean by hype.) Put in mundane terms -- but mundane terms that are unavoidable if you're actually going to play the piece -- the music was scored for three xylophones, some electric bells, three airplane propellers (two wood, one metal), a lot of percussion, four bass drums, a big gong, a siren, two pianos, and a player piano. For the Carnegie Hall performance, Carol Oja writes, "he expanded the scoring to six xylophones and ten pianos [!], reportedly also adding whistles, rattles, sewing machine motors, and two large pieces of tin." (I feel a little guilty, I have to add, quoting Carol Oja so much, because I was asked to review her book for The New York Times Book Review, and didn't like it much. But whatever its faults as a piece of writing, the information in it -- and in Oja's papers for specialist journals -- is invaluable.)

The Carnegie Hall

performance as quite an event, as you can see from some extracts from press coverage

in The New York Journal and

Elite subscribers of the Beethoven Association and the Philadelphia Orchestra rubbed shoulders with habitués of night clubs and vaudeville artists.

All the gals and fellas of [

The

But the performance itself had some problems.

The first few minutes...went off smoothly [the man who promoted the event later wrote], and the audience listened to it carefully. And then came the moment for the wind machine [he means the airplane propellers] to be turned on--and all hell, in a minor way, broke loose.

The propeller, Carol Oja explains, had unfortunately been aimed straight at part of the audience, and when it got up to speed, there was a minor disaster:

People clutched their programs, and women held onto their hats with both hands. [This is the promoter, once again.] Someone in the direct line of the wind tied a handkerchief to his cane and waved it wildly in the air in a sign of surrender.

When it came time for the siren, the man operating it

turned the crank wildly, while the audience, unable to contain itself any longer, burst once more into uncontrolled laughter. But there was no sound from the siren.

Eventually, when it did make some noise, it

[drowned] out the applause of the audience, covering the sound of the people picking up their coats and hats and leaving the auditorium.

So Ballet Méchanique was a failure. But not for everyone. I'm going to close with something fabulous that doesn't come from Carol Oja, but which I found in a collection of essays by William Carlos Williams, one of the great American poets of the last century. He was in Carnegie Hall that night, and first of all notes that "the audience stayed almost to a person until the end of the concert, even applauding wildly at the success of the final 'Jazz' Symphony."

But he also compares Ballet Méchanique to other music heard in Carnegie Hall, and I'm going to finish -- after all the perishable hype and excitement -- with his reflections, the words of an artist who understood something more:

Here is Carnegie Hall. You have heard something of the great Beethoven and it has been charming, masterful in its power over the mind. We have been alleviated, strengthened against life -- the enemy -- by it. We go out of Carnegie into the subway, and we can for a moment withstand the assault of that noise, failingly! as the strength of the music dies. Such has been its strength to enclose us that we may even feel its benediction a week long.

But as we came from Antheli's "Ballet Méchanique" a woman of our party, herself a musician, made this remark: "The subway seems sweet after that." "Good, I replied and went on to consider what evidences there were in myself in explanation of her remark. And this is what I noted. I felt that noise, the unrelated noise of life such as this in the subway had not been battened out as would have been the case with Beethoven still warm in the mind but it had actually been mastered, subjugated. Antheil had taken this hated thing life and rigged himself into power over it by his music. The offense had not been held, cooled, varnished over but annihilated and life itself made thereby triumphant. This is an important difference .By hearing Antheil's music, seemingly so much noise, when I actually came up on noise in reality, I found that "I had gone up over it."

If

you'd like to subscribe to this book -- which above all means you'll be

notified by e-mail when new episodes appear -- just click here, and write "subscribe to the

book" in the subject line of the e-mail form that'll appear. Subscribers

help me; I feel wonderfully encouraged each time somebody new asks to be put on

my subscription list. And please, if you would, to add a note to your e-mail,

and tell me something about yourself. I'm always curious about who's

subscribing, and why you're all interested. That often leads to an e-mail

exchange, and often enough to some sharing of ideas (from which I learn a lot).

Or let me put it this way: Even if you don't work in the classical music

business, you become part of the network of people who've helped me with the

book, which means (as I explained in episode six) that the book is partly

dedicated to you. I'll also offer special goodies to subscribers -- segments I

haven't published online, revisions of online episodes, the book proposal I'll

eventually send to a publisher, second thoughts on things I've written, special

comments, and other things I can't imagine yet.

Please

comment on the book. Below you'll see where you can post comments, which can

either appear with your name attached, or anonymously. Anyone who posts a

comment of course also becomes part of the network I'm so happy about. The

comments have helped me enormously.

My

privacy policy: I'll never share my subscriber list with anyone, for any

reason. I send all e-mail to my list myself, without

routing it through anyone at ArtsJournal. And I send

all e-mail with the names of the recipients hidden. All subscribers have their

privacy protected at all times. Further: if you e-mail me about the book, I'll

consider your e-mail private. I won't quote it in any public forum without your

permission. Comments you post here, though, of course appear in a public forum,

and thus can be freely quoted by me or by anyone else who reads them.

Posted by gsandow on November 28, 2006 11:51 PM

COMMENTS

Dear Mr. Sandow, I've only just read ch.15 of book2 and I appreciate this opportunity to respond. Music is not alone in it's professional obsession with the classical vs modern. Painters have been dealing with this too for the past 150 years, so much that evern the vocabulary of terms, (eg. classical, romantic, baroque, modern and oh of course "post-mod", are no longer clear concepts to artists or their critics. IN fact, when was the last time you read a good art criticsm? It's a dead profession. No one understands what's being written. I love what you have to say, and I'll read more when I have the time.

Thanks. I'm not sure that visual art is as locked in the past as classical music is, though. Contemporary and modern art events can be very big in New York. There were lines around the block, for instance, for a Jackson Pollock show at MOMA. Nothing like that would happen for the musical equivalent.

Posted by: Nicholas Vahlkamp at December 1, 2006 9:53 PM

Your observations about classical music and composers in the past are true up to a point,but

I would like to offer some historical perspective

to explain why I reject the notion that classical

music life was better,or"healthier in the past.

There are more orchestras and opera companies

today than ever before,so a greater variety of

repertoire is needed,both old and new music,than

ever before.It's not that there is a lack of new

music today.There is plenty of it.There is simply

greater diversity of classical music today than

ever before;this is not a bad thing at all;

in fact,it is wonderful to have so much variety.

No one complains that we can still read

literature from the past,or see visual art from

long ago;it does not prevent new art or literature

from getting exposure.So why should we complain

about the fact that classical music from the past is still performed?

I do not buy all the negative things you have been saying about performances of classical music today.Overall standards are very high,probably

higher than ever before.Or that concerts are the kind ofdreary events you describe.Audiences are in

fact often highly enthusiastic about what they hear.

Posted by: robert berger at December 5, 2006 10:28 AM