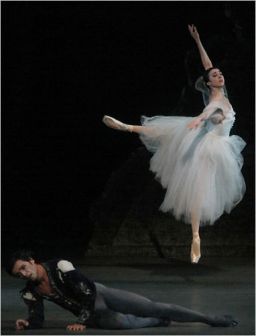

Albrecht and Giselle dancing…

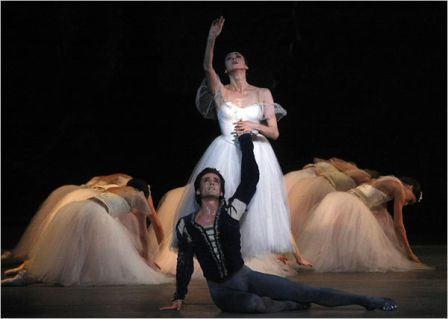

Albrecht and Giselle dancing… and dancing…

and dancing…

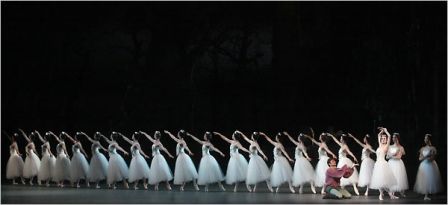

The choreography for the corps is so strong and was so well delivered July 7 (led by Melissa Thomas and an astounding Zhong-Jing Fang, whose arching back delineated a maelstrom of conflicting feelings with every arabesque) that the dancers became a sisterhood: a positive thing in itself, whatever its purpose. And Giselle won’t ever belong. For a ghostly eternity, she will be a pariah to the women and apart from the man she has saved. That she will always be in his heart hardly matters, since it won’t be within reach.

As lead Wili Myrta, Gillian Murphy underscored how much these women had lost. In her opening solo, she introduced the tribe with a steely chill: after bourreeing in and out of view like the wraith she is, she stopped dead in a perfect 90 degree arabesque, sharp and fine like a sword. But the bourrees, and the arms she wreathed around her torso, were so soft and sensual that you heard the music’s pathos. Murphy brought into focus how Myrta’s lethal resolve arises out of great hurt. (This is what an actor-dancer can do: illuminate the story.) I was also struck by the symmetry of Giselle and Albrecht’s romanceful dancing in Act I. It’s rare that a ballerina and her cavalier perform the same steps. He’s usually consigned to the heavy lifting that allo

ws her to float, plus some big jumps and turns. But in this 1841 ballet they leap and hop together. It’s such a nice Romantic touch, that despite the unevenness of their stations (he a prince, she a peasant), in love they dance alike. Forward to the Revolution!

Even in the tag-team endurance test that makes up most of Act II, Albrecht and Giselle do versions (inversions, really) of each other’s steps: her ghostly two-footed hops

(up and up and up and up!) and backward-moving ronde de jamb hops echo his cabriole beats and forward slides into assemble-entrechats. In the final moments, when they have come full circle, they return to mirroring each other. They once played together without a shadow of doubt. Now again there are no doubts, but many shadows.Nina Ananiashvili came into her own in the second act. She was bright, soft, determined, and a bit frightened by her own ghostly shell. Angel Corella has always been spectacular in the final scenes, but it was hard not to giggle when he’d throw himself recklessly into a turn and still manage a kabillion revolutions before the bar of music was out. You weren’t watching Albrecht, desperate for his life. You were watching cocksure Corella. Now when he’s closing in on dawn, he doesn’t look like he could get up and run through the whole trial again.

And when Giselle leaves him to make his way back to life, it’s not a moment of triumph or defeat but of acquiescence: he’s alive, but the woman he’s finally convinced he loves is gone. As the curtain falls, Corella looks out at us without relief or hope and walks with a steady, slow gait toward the lip of the stage.American Ballet Theatre should do “Giselle” every summer. Though surely the ballet has survived because it is better than most from the Romantic era, it makes me want to see some others, even ones in at least irregular rotation, such as “La Fille Mal Gardee” (how is the version by Nijinska, that latter-day revolutionary?) and “La Sylphide” (which I’ve never seen ABT do, though they have, not long ago. Perhaps if their latest version isn’t up to snuff, they could work out some sort of exchange with Nikolaj Hubbe, new Royal Danish Ballet head: you can have our best Fokine –“Petrushka” and “Les Sylphides”–for your “La Sylphide.”)

I’m grateful for how much dance matters to the “Giselle” libretto and how the ballet spares us

both the divertissements of the late 19th century that neither advance the story nor its themes and such rickety remains of Imperial thinking as those balletified folk numbers that invite us to play kings, queens, dukes, and duchesses and imagine the world is our precious oyster. However much “Giselle” is a fairytale, the core of the drama is real–not just that an aristocratic cad takes advantage of a woman and a peasant, but also that desire isn’t predictable, that he thought she wouldn’t matter but she did; that he thought he knew what joy was, but he didn’t, not until she showed up.And this motif complements the other emancipations that Romantics wrote about, rallied for, or at least sympathized with: the idea of elective affinities–a wonder about the phenomenology of desire

; the notion that feeling is inherently uncapturable and even unabatable, like the Sylphide whose dancing her lover James can’t control without it destroying her; the terror and triumph of the mob, the clan, the folk, the nation (a new idea, nationhood); the yearnings for nature, for natural man, for exchanging places with creatures (nightingales, sylphs, women and peasants [oops!]) who have no idea about this “I think, therefore I am” credo of the Enlightenment but who have gained by it: there would have been no Rights of Man without it, and no Romantics extending dignity even to those who didn’t think, or at least not like them.Granted, Petipa-Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake,” from the late 19th century, has all the supernatural elements of the Romantic ballet. There’s a swan-woman, fickle royalty, the unpredictability of love. But the lady swan is a queen from the start. She’s like Cinderella, who may look like a char girl but at heart is an aristocrat. Her wicked stepsisters, by contrast, are hopelessly bourgeois–gauche because striving. Odette the swan queen’s evil double, Odile, resembles the stepsisters not just in her wickedness, but in her ambition. She has no idea how to be demure: she is a brazen hussy.

Plus, by “Swan Lake” the ballroom interludes of ethnic dances had lost whatever sense they once had of celebrating nations budding out of fragmented former empires; the dance numbers were now simply a memento to the Czarist audience, world-traveling tourists.

I don’t think it’s an accident that you can trace the most glorious moments of the late 19th century ballets back to Romantic precedent: the morbid Kingdom of the Shades in Petipa’s “La Bayadere,” where the fickle warrior Solor dreams of an infinite peace far outside any kingdom’s grasp (like Keats’ anguished poet, De Quincey’s opium eater, and the dejected Coleridge seeing in the moon a “cloudless, starless lake of blue,” Solor is half in love with death); or Lev Ivanov’s chorus of swans in “Swan Lake” or snowflakes in “Nutcracker,” who embody the grace of

nature and culture merging; or the fairy solos at the birthday party in Petipa’s “The Sleeping Beauty,” in which each fairy bestows on baby Aurora her own unique gift–as unique as our individual pursuits of happiness. Together the fairies’ gifts make up a whole that is greater, even, than the sum of its marvelously idiosyncratic parts. For your viewing pleasure, here are the final moments of ABT’s 1977 “Giselle,” with Baryshnikov as Albrecht, Natalia Makarova as Giselle, and Martine Van Hamel (who performs character roles with the company these days–and she’s terrific) as Myrta. Baryshnikov interprets the ending very differently than Corella. He piles petals in his arms only to shed them like tears: life and happiness don’t last is the tragic fact he can’t get out from under as the ballet comes to a close.Here’s a minute of the audience going crazy at the July 7 curtain calls. MORE on Foot: For more on the “terror and triumph of the mob,” see Paul Parish’s incredible post from spring 2007, in which he discusses ballets by Eugene Loring, Bournonville, Forsythe, and several other choreographers. Related is a multipart discussion between Paul, Brian Seibert, and me on the corps in Balanchine’s “Serenade” (and the effect of the ensemble size in his “Liebeslieder Walzer”). That conversation begins with me, here (where there are links to subsequent posts).

Leave a Reply